| Indian yellow | |

|---|---|

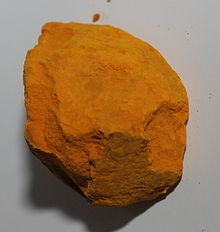

Indian yellow, historical dye collection of the Technical University of Dresden, Germany | |

| Hex triplet | #E3A857 |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (227, 168, 87) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (35°, 62%, 89%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (73, 73, 50°) |

| Source | The Mother of All HTML Colo(u)r Charts |

| ISCC–NBS descriptor | Moderate orange yellow |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) | |

Indian yellow is a complex pigment consisting primarily of euxanthic acid salts (magnesium euxanthate and calcium euxanthate),[1] euxanthone and sulphonated euxanthone.[2] It is also known as purree, snowshoe yellow, gaugoli, gogili, Hardwari peori, Monghyr puri, peoli, peori, peri rung, pioury, piuri, purrea arabica, pwree, jaune indien (French, Dutch), Indischgelb (German), yìndù huáng (Chinese), giallo indiano (Italian), amarillo indio (Spanish).[3]

The crystalline form dissolved in water or mixed with oil to produce a transparent yellow paint which was used in Indian frescoes, oil painting and watercolors. After application Indian yellow produced a clear, deep and luminescent orange-yellow color which, due to its fluorescence, appears especially vivid and bright in sunlight. It was said to be of a disagreeable odour.[4] It was most used in India in the Mughal period and in Europe in the nineteenth century, before becoming commercially unavailable circa 1921.[5]

The origin and manufacture of Indian yellow had long been disputed partly due to variations among the sources themselves which included both pure materials and mixtures of chrome salts, dyes of plant origin and those of animal origin. Studies in 2018 of a sample collected by T. N. Mukharji in 1883 give credibility to his observations that it was obtained from concentrated urine from cows fed on a diet of mango leaves.[6][7]

History[edit]

Indian yellow was widely used in Indian art, cloth dyeing and other products. It was noted for its intense luminance and was especially well known from its use in Rajput-Mughal miniature paintings from the 16th to the 19th century. It may have also been used in some wall paintings.[8] The pigment was imported into Europe and its use is known from some artists including Jan Vermeer who was long thought to have used Indian yellow in his Woman Holding a Balance (1662-1663),[9] since disproven by pigment analysis.[10] Indian yellow pigment is claimed to have been originally manufactured in rural India from the urine of cattle fed only on mango leaves and water. The urine would be collected and dried, producing foul-smelling hard dirty yellow balls of the raw pigment, called "purree".[11] The process was allegedly declared inhumane and outlawed in 1908,[5] but no record of these laws has been found.[12]

A description of the above process was given by T. N. Mukharji of Calcutta, who in response to a request from Sir Joseph Hooker, investigated an animal source in Monghyr, north-east Bihar, India.[13] Mukharji identified two sources, one of mineral origin and one of animal origin. The latter was of special interest and he noted how cows were fed with mango leaves, suffered from the poor nutrition, with the sparse urine having to be collected in small pots, cooled, and then concentrated over a fire. The liquid was then filtered through cloth and the sediment collected in balls, then dried over a fire and in the sun. Importers in Europe would then wash and purify the balls, separating greenish and yellow phases. Mukharji also sent a sample to Hooker. Hooker had part of the sample examined by the chemist Carl Gräbe, who took considerable interest in its chemistry. In a 2018 publication, the analysis of part of this sample was documented. It confirms the animal origin of the sample and identifies the source as urine based on hippuric acid which is a key marker. The pigment can be clearly distinguished by spectroscopic techniques.[14]

The Art of Painting in Oil and Fresco,[15] a translation of the French De la peinture à l’huile by Léonor Mérimée, states a possible source for the pigment:

...the coloring matter is extracted from a tree or large shrub, called Memecylon tinctorium, the leaves of which are employed by the natives in their yellow dyes. From a smell like cow's urine, which exhales from this colour, it is probable that this material is employed in extracting the tint of the memecylon.

In 1844, chemist John Stenhouse examined the origin of Indian yellow in an article published in the November 1844 edition of the Philosophical Magazine. At that time the balls of purree imported from India and China came in balls of around 3–4 oz (85–113 g) which when broken open showed a deep orange color. Viewed under a microscope, it showed small needle-shaped crystals, while its smell was said to resemble that of castor oil. Stenhouse reported that Indian yellow was commonly thought to either be composed of gallstones from different animals, including camels, elephants, and buffaloes, or deposited from the urine of some of these animals. He carried out a chemical analysis and concluded that he believed it was in fact of vegetable origin, and was "the juice of some tree or plant, which, after it has been expressed, has been saturated with magnesia and boiled down to its present consistence."[16]

In her 2002 book Colour: travels through the paintbox,[17] Victoria Finlay examined whether Indian yellow was really made from cow urine. The only printed source that she found mentioning this practice was the single letter written by T. N. Mukharji,[13] who claimed to have seen the color being made. Finlay was very skeptical as she found no oral evidence of the production of pigment in Mirzapur and she failed to find legal records concerning the supposed banning of Indian yellow production in Monghyr around 1908 as claimed by Mukharji. Other researchers have pointed out that this ban may have been possible on the basis of pre-existing Bengal acts for the prevention of animal cruelty 1869. However other researches have found many lines of evidence including Pahari paintings from c. 1400 that show the use of urine from cows fed on mango leaves.[9][18] Several studies in 2017 and 2018, including a re-examination of the sample supplied by Mukharji to Hooker confirm that Mukharji was accurate in his observation and highlights the origins of Indian yellow from urine by identifying metabolic studies on animals demonstrating euxanthic acid production through glucuronidation pathways in the liver.[6]

Modern alternatives[edit]

The replacement for the original pigment (which was not entirely resistant to light), synthetic Indian yellow hue, is a mixture of nickel azo, hansa yellow, and quinacridone burnt orange. It is also known as azo yellow light and deep, or nickel azo yellow. The main components of Indian yellow, euxanthic acid and its derivatives, can be synthesized in the laboratory.[19]

References[edit]

- ^ Nicholas Eastaugh; Valentine Walsh; Tracey Chaplin; Ruth Siddall (2004). The pigment compendium : a dictionary of historical pigments. Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 193. ISBN 978-0750657495. OCLC 56444720 – via Google Books.

- ^ Martin de Fonjaudran, Charlotte; Acocella, Angela; Accorsi, Gianluca; Tamburini, Diego; Verri, Giovanni; Rava, Amarilli; Whittaker, Samuel; Zerbetto, Francesco; Saunders, David (2017). "Optical and theoretical investigation of Indian yellow (euxanthic acid and euxanthone)" (PDF). Dyes and Pigments. 144: 234–241. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2017.05.034. ISSN 0143-7208.

- ^ "Indian yellow". www.getty.edu. Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus. Retrieved 2018-07-17.

- ^ Hepworth, Harry (1924). Chemical Synthesis. Studies in the Investigation of Natural Organic Products. Blackie and Son. p. 25.

- ^ a b Feller, Robert L., ed. (1986). "Indian Yellow". Artists' pigments : a handbook of their history and characteristics. N.S. Baer, A. Joel, R.L. Feller and N. Indictor. Washington: National Gallery of Art. pp. 17–36. ISBN 978-1-904982-74-6. OCLC 12804059.

- ^ a b Ploeger, Rebecca; Shugar, Aaron (2017). "The story of Indian yellow – excreting a solution". Journal of Cultural Heritage. 24: 197–205. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2016.12.001. ISSN 1296-2074.

- ^ Bailkin, Jordanna (2005). "Indian Yellow. Making and Breaking the Imperial Palette". Journal of Material Culture. 10 (2): 197–214. doi:10.1177/1359183505053075. ISSN 1359-1835. S2CID 143846855.

- ^ Tamburini, Diego; Martin De Fonjaudran, Charlotte; Verri, Giovanni; Accorsi, Gianluca; Acocella, Angela; Zerbetto, Francesco; Rava, Amarilli; Whittaker, Samuel; Saunders, David; Cather, Sharon (2018). "New insights into the composition of Indian yellow and its use in a Rajasthani wall painting" (PDF). Microchemical Journal. 137: 238–249. doi:10.1016/j.microc.2017.10.022.

- ^ a b Baer, N.S.; Indictor, N.; Joel, A. (1972). "The chemistry and history of the pigment Indian Yellow". Studies in Conservation. 17 (sup1): 401–408. doi:10.1179/sic.1972.17.s1.009. ISSN 0039-3630.

- ^ Gifford, E. M. (1998). "Painting Light: Recent Observations on Vermeer's Technique". In Ivan Gaskell; Michiel Jonker (eds.). Vermeer Studies. Symposium papers, Studies in the history of art. Vol. 33. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art. pp. 185–199. ISBN 978-0-300-07521-2. OCLC 40462569.

- ^ "Pigments through the Ages - History - Indian yellow". webexhibits.org. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ^ St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. p. 72. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- ^ a b Mukharji, T.N. (27 August 1883). "Piuri or "Indian yellow"". Journal of the Society of Arts. 32 (published 1884): 16–17.

- ^ Ploeger, R; Shugar, A; Smith, G.D; Chen, V.J (2019). "Late 19th century accounts of Indian yellow: The analysis of samples from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew". Dyes and Pigments. 160: 418–431. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2018.08.014. S2CID 105478380.

- ^ Taylor, W.B.S.; Mérimée, J.F.L. (1839). The Art of Painting in Oil and in Fresco. London: Whittaker & co. pp. 109.

- ^ Stenhouse, John (November 1844). "Examination of a yellow substance from India called Purree, from which the pigment called Indian Yellow is manufactured". London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 25: 321–325.

- ^ Finlay, Victoria (2003). Color: A Natural History of the Palette. Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-7142-2.

- ^ Khandalavala, K. (1958). Pahari Miniature Painting. Bombay: New Book.

- ^ Perkin, Arthur George; Everest, Arthur Ernest (1918). The natural organic colouring matters. London: Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 127–129.

External links[edit]

- Indian yellow, ColourLex

- Indian yellow, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.