| Battle of Sobraon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Anglo-Sikh War | |||||||

Sardar Sham Singh Attariwala rallying Sikh cavalry for the last stand | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

26,000 70 guns[1] |

20,000 35 siege guns 30 field or light guns[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 8,000–10,000, 67 guns captured [2] | 2,300 [2] | ||||||

The Battle of Sobraon was fought on 10 February 1846, between the forces of the East India Company and the Sikh Khalsa Army, the army of the Sikh Empire of the Punjab.[3][4] The Sikhs were completely defeated, making this the decisive battle of the First Anglo-Sikh War.

Background[edit]

The First Anglo-Sikh war began in late 1845, after a combination of increasing disorder in the Sikh empire following the death of Ranjit Singh in 1839 and provocations by the British East India Company led to the Sikh Khalsa Army invading British territory. The British had won the first two major battles of the war through a combination of luck, the steadfastness of British and Bengal units and deliberate treachery by Tej Singh and Lal Singh, the commanders of the Sikh Army.

On the British side, the Governor General, Sir Henry Hardinge, had been dismayed by the head-on tactics of the Bengal Army's commander-in-chief, Sir Hugh Gough, and was seeking to have him removed from command. However, no commander senior enough to supersede Gough could arrive from England for several months. Then the army's spirits were revived by the victory gained by Sir Harry Smith at the Battle of Aliwal, in which he eliminated a threat to the army's lines of communication, and the arrival of reinforcements including much-needed heavy artillery and two battalions of Gurkhas.

The Sikhs had been temporarily dismayed by their defeat at the Battle of Ferozeshah, and had withdrawn most of their forces across the Sutlej River. The Regent Jind Kaur who was ruling in the name of her son, the infant Maharaja Duleep Singh, had accused 500 of her officers of cowardice, even flinging one of her garments in their faces.

The Khalsa had been reinforced from districts west of Lahore, and now moved in strength into a bridgehead across the Sutlej at Sobraon, entrenching and fortifying their encampment. Any wavering after their earlier defeats was dispelled by the presence of the respected veteran leader, Sham Singh Attariwala. Unfortunately for the Khalsa, Tej Singh and Lal Singh retained the overall direction of the Sikh armies. Also, their position at Sobraon was linked to the west, Punjabi, bank of the river by a single vulnerable pontoon bridge. Three days' continuous rain before the battle had swollen the river and threatened to carry away this bridge.

The battle[edit]

Gough had intended to attack the Sikh army as soon as Smith's division rejoined from Ludhiana, but Hardinge forced him to wait until a heavy artillery train had arrived. At last, he moved forward early on 10 February. The start of the battle was delayed by heavy fog, but as it lifted, 35 British heavy guns and howitzers opened fire. The Sikh cannon replied. The bombardment went on for two hours without much effect on the Sikh defences. Gough was told that his heavy guns were running short of ammunition and is alleged to have replied, "Thank God! Then I'll be at them with the bayonet."

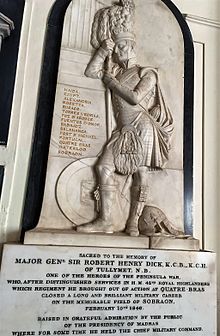

Two British divisions under Harry Smith[5] and Major General Sir Walter Gilbert made feint attacks on the Sikh left, while another division under Major General Robert Henry Dick made the main attack on the Sikh right, where the defences were of soft sand and were lower and weaker than the rest of the line. (It is believed that Lal Singh had supplied this information to Major Henry Lawrence, the Political Agent at Gough's headquarters.) Nevertheless, Dick's division was driven back by Sikh counter-attacks after initially gaining footholds within the Sikh lines. Dick himself was killed. As the British fell back, some frenzied Sikh soldiers attacked British wounded left in the ditch in front of the entrenchments, enraging the British soldiers.

The British, Gurkhas and Bengal regiments renewed their attacks along the entire front of the entrenchment, and broke through at several points. On the vulnerable Sikh right, engineers blew a breach in the fortifications and British cavalry and horse artillery pushed through it to engage the Sikhs in the centre of their position. Tej Singh had left the battlefield early. It is alleged in many Sikh accounts that he deliberately weakened the pontoon bridge, casting loose the boat at its centre, or that he ordered his own artillery on the west bank to fire on the bridge on the pretext of preventing British pursuit. British accounts claim that the bridge, having been weakened by the swollen river, simply broke under the weight of the numbers of soldiers trying to retreat across it. Whichever account is correct, the bridge broke, trapping nearly 20,000 of the Sikh Khalsa Army on the east bank.

None of the trapped Sikh soldiers attempted to surrender. Many detachments, including one led by Sham Singh Attariwala, fought to the death.[6] Some Sikhs rushed forward to attack the British regiments sword in hand; others tried to ford or swim the river. British horse artillery lined the bank of the river and continued to fire into the crowds in the water. By the time the firing ceased, the Sikhs had lost between 8,000 and 10,000 men.[7] The British had also captured 67 guns.

Aftermath[edit]

The destruction of the bridge did not delay Gough at all, if this had indeed been Tej Singh's intention. The first British units began to cross the river on the evening of the day of battle, and on 13 February, Gough's army was only 30 miles (48 km) from Lahore, the Sikh empire's capital. Although detachments of the Khalsa remained intact in outlying frontier districts of the Punjab, they could not be concentrated quickly enough to defend Lahore.

The central durbar of the Punjab nominated Gulab Singh, the effective ruler of Jammu, to negotiate terms for surrender. By the Treaty of Lahore, the Sikhs ceded the valuable agricultural lands of the Bist Doab (Jullundur Doab) (between the Beas and Sutlej Rivers) to the East India Company, and allowed a British Resident at Lahore with subordinates in other principal cities. These Residents and Agents would indirectly govern the Punjab, through Sikh Sardars. In addition, the Sikhs were to pay an indemnity of 1.2 million pounds. Since they could not readily find this sum, Gulab Singh was allowed to acquire Kashmir from the Punjab by paying 750,000 pounds to the East India Company.

Order of battle[edit]

British regiments[edit]

- 3rd King’s Own Light Dragoons

- 9th Queen’s Royal Light Dragoons (Lancers)

- 16th The Queen's Lancers

- 9th Foot

- 10th Foot

- 29th Foot

- 31st Foot

- 50th Foot

- 53rd Foot

- 80th Foot

British Indian Army regiments[edit]

- Governor General’s Bodyguard

- 3rd Bengal Native Cavalry

- 4th Bengal Native Cavalry

- 5th Bengal Native Cavalry

- 2nd Bengal Irregular Cavalry

- 4th Bengal Irregular Cavalry

- 8th Bengal Irregular Cavalry

- 9th Bengal Irregular Cavalry

- 1st Bengal European Regiment

- 4th Bengal Native Infantry

- 5th Bengal Native Infantry

- 16th Bengal Native Infantry

- 26th Bengal Native Infantry

- 31st Bengal Native Infantry

- 33rd Bengal Native Infantry

- 41st Bengal Native Infantry

- 42nd Bengal Native Infantry

- 43rd Bengal Native Infantry

- 47th Bengal Native Infantry

- 59th Bengal Native Infantry

- 62nd Bengal Native Infantry

- 63rd Bengal Native Infantry

- 68th Bengal Native Infantry

- 73rd Bengal Native Infantry

- Nasiri Battalion (1st Gurkha Rifles)

- Sirmoor Battalion (2nd Gurkha Rifles)

Folklore and personal accounts[edit]

Several years after the battle, Gough wrote,

"The awful slaughter, confusion and dismay were such as would have excited compassion in the hearts of their generous conquerors, if the Khalsa troops had not, in the early part of the action, sullied their gallantry by slaughtering and barbarously mangling every wounded soldier whom, in the vicissitudes of attack, the fortune of war left at their mercy."

After hearing of the battle, the wife of Sham Singh Attariwala immolated herself on a funeral pyre without waiting for news of her husband, convinced (correctly) that he would never return alive from such a defeat.

Some accounts state that Lal Singh was present on the battlefield, and accompanied Tej Singh on his retreat. Other sources maintain that he commanded a large body of gorchurras (irregular cavalry) which was some miles away, and took no action against Gough's army although he might have attacked Gough's communications.

A long-standing friendship between the 10th (Lincolnshire) Regiment and 29th (Worcestershire) Regiment was cemented at the battle when their two battalions met in the captured trenches that had cost so many lives to take. For many years afterwards, it was the custom that sergeants and officers were honorary members of each other's messes and the adjutants of the two regiments addressed each other as 'My Dear Cousin' in official correspondence

Popular culture[edit]

The battle provides the climax for George MacDonald Fraser's novel, Flashman and the Mountain of Light. It is mentioned in Rudyard Kipling's Stalky & Co

See also[edit]

- 9th Regiment of Foot

- 53rd Regiment of Foot

- 1st King George V's Own Gurkha Rifles (The Malaun Regiment)

- 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles)

- 101st Grenadiers

- Jat Regiment

References[edit]

- ^ a b Hernon, p. 567

- ^ a b Holmes, Richard (2006). Battlefield: Decisive Conflicts in History.

- ^ Randhawa, Kirpal Singh (1999). "'We Won the Battle but Lost the Fight': Chillianwala 1849". Nishaan Nagaara magazine – premiere issue (PDF). pp. 41–53.

- ^ Sidhu, Amarpal Singh (2016). "Chronology". The Second Anglo-Sikh War. John Chapple (1st ed.). United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445650241.

- ^ Smith, Sir Harry. ‘’The Autobiography of Lieutenant-General Sir Harry Smith Baronet of Aliwal on the Sutlej.’’ Publisher: John Murrat, Albemarle Street, 1903 [1]

- ^ Singh, Harbans (2004). Encyclopedia of Sikhism. Vol. 4: S–Z (2nd ed.). Punjabi University, Patiala. pp. 343–344.

- ^ Holmes, Richard (2006). Battlefield: Decisive Conflicts in History.

- ^ Cotton, Julian James (1945). List Of Inscriptions On Tombs & Monuments in Madras Vol 1. Madras, British India: Government Press. p. 488. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

Bibliography[edit]

- Hernon, Ian (2003). Britain's forgotten wars. Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-3162-0.