Around 10,000 Lebanese-Armenians marching on April 24, 2006, on the 91st anniversary of the Armenian genocide | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Core population: 156,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Beirut (Ashrafieh) Mezher Bourj Hammoud Anjar Antelias Zahle | |

| Languages | |

| Armenian (Western) · Arabic · French · Turkish[2][3][4][5] | |

| Religion | |

| Armenian Apostolic Church • Armenian Catholic Church • Armenian Evangelical Church |

| Part of a series on |

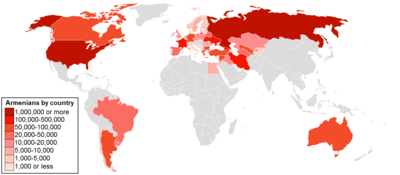

| Armenians |

|---|

|

| Armenian culture |

| By country or region |

Armenian diaspora Russia |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

|

| Persecution |

Armenians have lived in Lebanon for centuries. According to Minority Rights Group International, there are 156,000[1] Armenians in Lebanon, around 4% of the population. Prior to the Lebanese Civil War, the number was higher, but the community lost a portion of its population to emigration.

Lebanon experienced a significant migration of Armenian refugees primarily between 1918 and 1920, seeking sanctuary from the Armenian genocide carried out by Ottoman authorities. These refugees established Bourj Hammoud, a suburb east of Beirut, in the site of what was then a swampy marshland. Another wave of migration occurred in 1939, as refugees fleeing the Turkish annexation of Alexandretta founded the town of Anjar in the Beqaa region.[6] The Armenian population gradually grew and expanded until Beirut (and Lebanese towns like Anjar) became a center of Armenian culture. The Armenians became one of Lebanon’s most prominent and productive communities.[7]

Armenians in Lebanon strive to balance their Lebanese identity with ties to their homeland, keeping a distance from sectarian divisions. In areas like Bourj Hammoud and the coastal area northeast of Beirut, they maintain Armenian-language media and political parties. While most adhere to the Armenian Apostolic Church, there are also Armenian Protestants and Catholics.[6]

History[edit]

Armenians first established contact with Lebanon when Tigranes the Great conquered Phoenicia from the Seleucids and made it part of his short-lived Armenian Empire. When the Roman Empire established its rule over both Armenia and ancient Lebanon, some Roman troops of Armenian origin went there in order to accomplish their duties as Romans. After Armenia converted to Christianity in 301, Armenian pilgrims established contact with Lebanon and its people on their way to Jerusalem; some of whom would settle there.[8]

The Catholic Armenians who fled to Lebanon in the declining years of the 17th century may be credited with establishing the first enduring Armenian community in the land.[9] The Maronites further acted on the Armenians' behalf in 1742, when they interceded with the Vatican to win Papal recognition for the patriarch of the Armenian Catholics. In 1749, the Armenian Catholic Church built a monastery in Bzoummar, where the image of Our Lady of Bzommar is venerated. The monastery is now acknowledged as the oldest extant Armenian monastery in Lebanon. Alongside it was built the patriarchal see for the entire Armenian Catholic Church.[9]

In 1890's the Hamidian massacres had produced a trickle of Armenian refugees into Lebanon.

Armenians in Lebanon (1915–1975)[edit]

The Armenian presence in Lebanon during the Ottoman period was minimal; however, there was a large influx of Armenians after the Armenian genocide of 1915. Other Armenians inhabited the area of Karantina (literally "Quarantine", a port-side district in the Lebanese capital of Beirut). Later on, a thriving Armenian community was formed in the neighbouring district of Bourj Hammoud.

In 1939, after the French ceded the Syrian territory of Alexandretta to Turkey, Armenians and other Christians from the area moved to the Bekaa Valley. The Armenians were grouped in Anjar, where a community exists to this day. Some of these Armenian refugees had been settled by the French mandate authorities in camps in the South of Lebanon: El Buss and Rashidieh camps in Tyre would later make way for Palestinian refugees.[10]

Prior to 1975, Beirut was a thriving center of Armenian culture with varied media production,[11] which was exported to the Armenian diaspora.

Armenians in Lebanon (1975–present)[edit]

During the Lebanese Civil War, Armenians, grouped in Bourj Hammoud and Anjar, have been known for their neutrality in the civil war.[12] And while the insecurity and economic dislocation of the war caused Lebanese Armenians to lose much of their number to emigration, the distinctive features and manifold successes of the community yet remain.[9]

There are three prominent Armenian political parties in Lebanon: the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (also Dashnak or Tashnag), Social Democrat Hunchakian Party (Hunchag) and Armenian Democratic Liberal Party (Ramgavar Party). They play significant influence in all facets of Armenian life. During the civil war militant organizations, such as ASALA, became active in Lebanon, and used it as a launching pad for their operations. ASALA was founded in 1975 in Beirut, during the Lebanese Civil War by Hagop Hagopian, pastor Reverend James Karnusian[13] and Kevork Ajemian,[14] a prominent contemporary writer, with the help of sympathetic Palestinians.[15]

More than 150,000 Lebanese-Armenians have political representation in 6 seats in the Lebanese Parliament, in addition to one ministerial position.[7]

Lebanon was one of the region’s first nations and the first Arab League member to recognize the Armenian genocide. The Armenian bloc of the Lebanese Parliament put forth a resolution, calling for the commemoration of the anniversary of the Armenian genocide; the legislature unanimously approved the resolution on 4 April 1997[16] In May 2000, the Lebanese Parliament approved a resolution calling for the commemoration of the Genocide’s 82nd anniversary and called on all Lebanese citizens to unite with the Armenian people every April 24 to commemorate it.[7]

On 4 August 2020, during the 2020 Beirut explosions, 15 Armenians were killed,[17] more than 250 injured, the Armenian Catholicosate in Antelias suffered great material damage, Armenian churches and the building of Haigazian University have been damaged.[18][19][20]

Armenian neighborhoods[edit]

Armenians live in many parts of Lebanon. Historically most Armenians have lived in Beirut and Matn District and Anjar in the Bekaa Region. From Beirut proper we can mention grander Ashrafieh: Hadjen (Corniche Nahr), Khalil Badawi, Karm el Zeytoun (Հայաշէն), Rmeil, Gemmayze, Mar Mikhael, Sursock, and Geitawi. Armenians have had strong presence also in other Beirut regions such as Khandaq Ghamik, Zuqaq al-Blat, Zarif, Bab Idris, Sanayeh (Kantari), Clemenceau and Hamra, among others. During the civil war many of these Armenians emigrated or fled to safer regions in Lebanon. From the Beirut suburbs, there are big concentrations in Matn District, particularly Bourj Hammoud, Dora-Amanos, Fanar, Rawda, Jdeide, Zalka, Jal El Dib, Antelias, Mezher (Dzaghgatzor), Naccash, Dbayeh, Awkar and in the regions situated from Antelias to Bikfaya. To the north, there are further Armenian populations scattered in Jounieh, Byblos and Tripoli (particularly the Mina area). Anjar is a place where Armenian populations is predominant.[citation needed]

There are Armenian religious centers in Antelias and Bikfaya (Armenian Apostolic Church) and Beirut and Bzommar (Armenian Catholic Church). There is an Armenian orphanage in historic sites in Byblos.

In the Bekaa, there are Armenians living in Zahlé and most notably Anjar.

Bourj Hammoud[edit]

Bourj Hammoud (Armenian: Պուրճ Համուտ, Arabic: برج حموﺪ) is a suburb in east Beirut, Lebanon in the Metn district. The suburb is heavily populated by Armenians as it is where most survivors of the Armenian genocide settled. Bourj Hammoud is an industrious area and is one of the most densely populated cities in the Middle East. It is divided into seven major regions, namely Dora, Sader, Nahr Beirut, Anbari, Mar Doumet, Naba'a and Gheilan. It is sometimes called "Little Armenia".[21] Bourj Hamoud has a majority Armenian population but also has a notable number of other Lebanese Christians, a considerable Shi'a Muslim population, a Kurdish population, and some Palestinian and newcomer Christian refugees from Iraq. Most streets in Bourj Hammoud are named after various Armenian cities such as Yerevan, mountains such as Aragats, and rivers such as Araks. A lot of streets are also named after cities and regions in modern-day-Turkey which were heavily populated by Armenians such as Cilicia, Marash, Sis, Adana, etc.[citation needed]

Mezher (Dzaghgatzor)[edit]

Mzher (or Dzaghgatzor in Armenian) is a small town located between Antelias and Bsalim, in Matn district. It is a new town, where most of the population is Armenian, along with other Christians. In Mzher the Armenian community has one of the top Armenian schools, Melankton and Haig Arslanian College (Jemaran) and a socio-cultural sport club, Aghpalian. The headquarters of SAHALCO are also situated nearby. Most of the Armenians of Mzher come from Bourj Hamoud, Ashrafieh, Anjar and the other old Armenian quarters.

Anjar[edit]

Anjar (عنجر, Այնճար), also known as Haoush Mousa (حوش موسى), is a town of Lebanon located in the Bekaa Valley. The population is about 2,400 consisting almost entirely of Armenians.

Jbeil[edit]

Jbeil-Byblos (جبيل, Ժիպէյլ), is a town of Lebanon located in the Keserwan-Jbeil_Governorate. Armenians in Jbeil count around 200 Armenian family. In Jbeil the Armenian community has the Armenian Community Center (ՃԻՊԷՅԼԻ ՀԱՅ ԿԵԴՐՈՆ) [22] including : A.R.F Hohita Keri Gomide,[23] Armenian Relief Cross Sosse chapter, Lebanese Armenian Youth Federation Ararad chapter, Serop Aghpuir Badanegan Miyoutioun, Birds Nest Orphanage,[24] Sourp gayane Church. an additional 40 Armenian families live in the neighboring city of Batroun.

Politics[edit]

According to the traditional Lebanese confessional representation in the Lebanese Parliament, a certain number of seats have been reserved for Armenian candidates according to their confession. Presently the Lebanese-Armenians are represented in the 128-seat Lebanese Parliament with 6 guaranteed seats (5 Armenian Orthodox and 1 Armenian Catholic) as follows:

- 3 Armenian Orthodox and 1 Armenian Catholic seat in the Beirut I electoral district

- 1 Armenian Orthodox seat in the Matn District

- 1 Armenian Orthodox seat in Zahle District

As many Protestants in Lebanon are ethnic Armenians, the sole parliamentary slot for Evangelical (Protestant) community has at times been filled by an Armenian, making for a total of 7 Armenian deputies in the Lebanese Parliament. Lebanese Armenians have been represented in government by at least one government minister in the formations of Lebanese governments. In case of larger governments (with 24 ministers and above) Armenians are traditionally given two government ministry positions. Lebanese-Armenians also have their quota in top-level public positions. [citation needed]

Unlike the Maronite Church and other religious groups in Lebanon, the Armenian Apostolic Church is not a political actor in its own right. Armenians do, however, enjoy political representation in Lebanon's multiconfessional government. Since the Cold War era, the Armenian Apostolic Church has participated in politics as a proxy for the nationalist Dashnak party.[26]

Education[edit]

Lebanon is the location of the only Armenian university outside Armenia. Haigazian University was established in Beirut by the Armenian Missionary Association of America and the Union of the Armenian Evangelical Churches in the Near East.[27] Founded in 1955, Haigazian is a liberal arts Armenian institution of higher learning, which uses English as the language of instruction.

Most Armenian schools are run by the three Armenian Christian denominations (Orthodox, Catholic and Evangelical). Others are run by cultural associations like Hamazkayin and Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU). [citation needed] Notable schools include:

- Armenian Evangelical College (Beirut)

- Armenian Evangelical Central High School (Ashrafieh, Beirut)

- Armenian Evangelical Shamlian Tatigian Secondary School (Bourj Hamoud)

- Yeghishe Manoukian College (Debbayeh)

- Hamazkayin Melankton & Haig Arslanian Djemaran School (Mezher)

- United Armenian College (Bourj Hammoud)

- Mesrobian College (Bourj Hammoud)

Culture[edit]

Music[edit]

Anatolian and kef music were a source of controversy due to the shared Ottoman past they represented in the post-genocide era. A combination of factors in Lebanon, including political independence and the strength of various Armenian institutions, created conditions that were permissive of the rise of an Armenian nationalism that was similar to the Turkish nationalism that emerged in the Ottoman Empire in the years leading up to the 1915 genocide. Music in the Lebanese diaspora became another means to separate "us" and "them", but also provided a space where Lebanese Armenians could connect with a concept of "home" in place of the Ottoman past and Soviet present.[27]

Community choirs that formed in Lebanon during the 1930s, led by former students of Komitas, utilized the imagery of Komitas as the saint and martyr of Armenian music. These choirs proved to be critical in the development of collective identity amongst Lebanese Armenians. According to Sylvia Angelique Alajaji, a professor of music who has studied music in the Armenian diaspora, "in a literal and symbolic sense, the songs sung by the choirs articulated home and articulated belonging."[27]

Armenian pop music thrived in 1970s Lebanon, until the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War. Many artists fled Lebanon during those years including pop singer Adiss Harmandian and classical soprano singer Arpine Pehlivanian. Songs were released about the war including one by Manuel Menengichian with the lyrics "Brothers turned into lions against each other/ Tearing up your heart, Lebanon".[28]

Theater[edit]

Like other cultural institutions of the Lebanese Armenian community, Armenian theater suffered during the years of the Lebanese Civil War. Many prominent figures decided to leave Lebanon; Berge Fazlian, founder of the Vahram Papazian group, was among those who fled during the wartime violence. Though theater experience a decline during the war years, it does not disappear entirely; the groups that remained in Lebanon were able to put on productions that filled the two theraters of Bourj Hammoud.[28]

Fazlian is considered one of the most important figures in Lebanese theater; his theater projects were covered in Armenian, Arabic and French-language newspapers of the period. Fazlian was born in Istanbul in 1926; after obtaining his education in Turkey and directing several plays, a friendly colleague advised him to seek his fortune outside Turkey, imploring Fazlian to "never leave the theater", but also reminding him that an Armenian was not likely to land a leading role in Turkey. Fazlian left Istanbul in 1951 and settled in Beirut where he founded the Nor Pem (“New Stage”) theater group in 1956, Vahram Papazian in 1959, and Azad Pem (“Free Stage”) in 1971.[29]

Lebanon had only one theater group in Beirut prior to Fazlian's creation of the Vahram Papazian group and that was Hamazkayin's Kasbar Ipegian theater company. Ipegian, who had settled in Beirut in 1930, was one of Hamazkayin's founders. Hamazkayin was the cultural arm of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) or Dashnak party. The Hamazkayin Theater Association, which Ipegian founded in 1941, performed plays created by Armenian writers like Levon Shant and Papken Papazian. Their self-stated mission was to "reestablish and spread the art of theater in the diaspora". This included enhancing "Armenian theater’s educational role in the preservation of national identity".[30][29]

Fazlian himself was a leftist and his group was associated the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU), while Ipegian's group was associated with Hamazkayin and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF). There was a rivalry between the two groups.[28] Before Fazlian's group the only plays available were partisan plays presented by members of the ARF and their sympathesizers, who would perform in the Hamazkayin plays. On the other hand, Fazlian's Vahram Papazian group performed a variety of plays that included Western Armenian, Eastern Armenian and even non-Armenian plays.[29]

Women[edit]

In 1932 Siran Seza, a Lebanese-Armenian writer, began publishing the first feminist literary review for women in Lebanon called The Young Armenian Woman (Armenian: Երիտասարդ Հայուհի, romanized: Yeritasard Hayuhi). Seza was born in Constantinople (present day Istanbul) in 1903.[31] Seza had translated Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther into Armenian when she was 15; her talent was recognized by Armenian poets of the era, such as Vahan Tekeyan, which led to her work being published in important literary journals of that time.[32] The final issue of The Young Armenian Women was published in 1968.[33]

The Armenian community in Lebanon developed educational institutions and organizations to address issues like poverty, which were exacerbated by the violent conflict and crisis in Lebanon. The focus of these institutions was on women's role as mothers, which is not uncommon in times of war or violent conflict. They sought to kept Armenian children connected to the community by offering cultural activities like traditional Armenian dance and music. The three main Armenian churches ran private Armenian schools for the children; even the poorest Armenian families tried to enroll their children in private Armenian schools and they often needed NGO assistance to pay for the schoolbooks.[34]

Life in the Armenian community of Bourj Hammoud was largely effected by gender. Non-Armenian men, even those who married Armenian women, rarely carried significant influence (wasta) in the community's social networks. For example, access to the only low-income housing for Armenians was governed by a set of "unofficial rules"; in practice, this meant that Armenian men married to non-Armenian women could rent or purchase an apartment in the housing project, but Armenian women married to non-Armenian men would face significant hurdles to secure this type of housing.[34]

Economy[edit]

Armenian American historian Richard G. Hovannisian has described what he calls the "economic vivacity" of the Armenian community in Lebanon in terms of the hundreds of Armenian owned shops in Beirut. The city's business quarter closes down on April 24, on the anniversary of the Armenian genocide.[35]

In the years after World War II, between 1946 and 1948, the Soviet Union sponsored a repatriation campaign encouraging Armenians living in diaspora to move to Soviet Armenia. In Beirut, which had a relatively large Armenian community, the repatriation campaign impacted the economy and destabilized the community. As Armenians emigrated from Beirut, property values deflated and lower income Arabs (some of them Shi'a) began to move into the Armenian quarters of the city. Hovannisian has written that "This unwelcome infiltration of culturally less developed and rapidly multiplying Muslim elements has been bemoaned by the affected Armenians for a quarter of a century."[35]

Media[edit]

"Pyunik" (Armenian: Փիւնիկ) was the first Armenian newspaper in Lebanon renamed Nor Pyunik (Armenian: Նոռ Փիւնիկ). In 1924, the newspaper Lipanan (Armenian: Լիբանան) was published. In 1927, Aztag replaced Nor Punik.

Press: Dailies[edit]

There are three Armenian daily newspapers published in Beirut all mouthpieces of the traditional Armenian political parties (Tashnag, Hunchag and Ramgavar).

- Aztag (Armenian: Ազդակ), a daily newspaper that speaks on behalf of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation – Tashnag and was established in 1927. It also published an online English version and an online Arabic supplement.

- Ararad (Armenian: Արարատ), a daily newspaper published by the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party – Hunchag Party

- Zartonk (Armenian: Զարթօնք), daily newspaper is published by Armenian Democratic Liberal Party – Ramgavar and was established in 1937.

From the defunct Armenian political newspapers besides Pyunik in the 1920s, one should mention the independent non-partisan newspaper Ayk (Armenian: Այգ) (after decades of publishing in Armenian, the licence owner Lucie Tosbat sold it to Monday Morning Publishing Group and Ayk started publishing as an English-language daily renamed Ike before folding.) Ayk daily's Lebanese-Armenian publishers Dikran and Lucie Tosbat also published the French language Le Soir.

Special mention should also be made for the Armenian leftist daily newspaper Joghovourti Tsayn (Armenian: Ժողովուրդի Ձայն meaning Voice of the People) which had a short span of publication but remained influential during its span of publication. [citation needed]

Press: Weekly publications and periodicals[edit]

Lebanon has a history of periodicals and weekly newspapers in the Armenian language. Notable long-running publications include:

- Hask (Հասկ), official publication of the Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia (Armenian Apostolic)

- Avedik (Աւետիք), official publication of the Armenian Catholic Church

- Yeridasart Hayouhi (Երիտասարդ Հայուհի, literary periodical dedicated to women) which was later turned into an independent political biweekly called Yeridasart Hay (Երիտասարդ Հայ).

- Nor Gyank (Նոր Կեանք, meaning New Life) the lifestyle newspaper/magazine

- Gantch (Կանչ), the Armenian Communist weekly (part of Arabic language communist "An Nidaa")

- Khosnag (Խօսնակ), the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) official publication

- Pakine (Բագին) literary cultural publication

- Shirak (Շիրակ) literary cultural publication

- Spurk (Սփիւռք meaning diaspora) literary and cultural publication

- Nayiri (Նայիրի) literary and cultural publication

- Massis (Մասիս), Armenian Catholic publication

- Badanegan Artsakank (Պատանեկան Արձագանք) Armenian Evangelical / Youth publication

Academic publications[edit]

- Hasg Hayakidagan Hantes, an annual Armenological publication by the Holy See of Cilicia

- Haigazian Armenological Review, an annual Armenological publication of Haigazian University

Radio[edit]

The Lebanese state radio established very early on daily radio broadcasts in Armenian through its second channel consecrated to broadcasting in languages (mainly French and English). That programming goes on to date on Radio Liban. During the civil war, the Lebanese Armenians established a great number of unlicensed radio stations (some non-stop for 24 hours a day). The pioneer was the popular radio station "Radio Paradise" and later on "Vana Tsayn" (Voice of Van). However, with the Lebanese Parliament enacting laws organizing the airwaves, all the unlicensed stations (alongside the other Lebanese stations) had to close. They were replaced by two operating and fully licensed radio stations operating in Armenian in Lebanon in accordance with the new broadcast laws – "Voice of Van" and "Radio Sevan". [citation needed]

Television[edit]

Lebanese private stations and state-owned Tele-Liban have consecrated occasionally television programming in Armenian on certain occasions. During the Lebanese civil war, an Armenian television station "Paradise Television" co-operated with "Radio Paradise" was established through a broadcast tower in Bourj Hammoud. But "Paradise Television" Armenian television station had to close after it failed to get a broadcasting licence according to the new laws organizing the airwaves. Al Mustaqbal Television (also known as Future Television) and OTV broadcast daily 30-minutes news and comments in Armenian in their regular programming schedule. [clarification needed]

Religion[edit]

Officially, there are three Armenian denominations recognized by the government. The Armenians have Armenian Orthodox, Armenian Catholic, or Armenian Evangelical mentioned in their identity cards, in the denomination field. Sometimes, however, there are variations particularly in case of the Armenian Evangelicals, sometimes registered as just Evangelicals or Protestants without mention of Armenian. There are also some Armenian Catholics who are registered under the denomination Latin, sometimes Armenian Latin. [citation needed]

Apostolic (Orthodox) Armenians[edit]

The Holy See of Cilicia is located in Antelias (a northern suburb of Beirut). It was relocated there in 1930 from Sis (historical Cilicia, now in Turkey) after the Armenian genocide. Alongside the Mother See of Holy Echmiadzin located in Armenia, it is one of the two sees of the Armenian Apostolic Church (the national church of Armenians). The Catholicos, the leader of the Holy See of Cilicia, has his summer residence in Bikfaya in the Matn District also north of Beirut. The seminary of the Armenian Apostolic Church is also on site at Bikfaya. The affairs of the Lebanese Armenian Orthodox population however are run by an independent body, the Armenian Prelacy of Lebanon (Aratchnortaran Hayots Lipanani) with its own Armenian Primate of Lebanon Bishop Shahé Panossian as head. [citation needed]

The Armenian Apostolic churches in Lebanon include:

- The Saint Gregory the Illuminator Mother Cathedral (Sourp Krikor Lousavoritch Mayr Dajar) which serves as the church for the Holy See of Cilicia (Catholicossate of the Great House of Cilicia – In Armenian "Gatoghigosaran Medzi Danen Guiligio" (Antelias, Lebanon). The big complex also contains a memorial chapel dedicated to the victims of the Armenian genocide, an Armenian library, printing presses, Armenian museum and "Veharan", residence of the catholicos of Cilicia and premises for the clergy.

- Holy Sign (Saint Nshan) Armenian Orthodox Church (Downtown Beirut) which serves as the church for the Armenian Apostolic Archbishopric of Lebanon and head office of the Armenian Primate of Lebanon.

- Saint Hagop Armenian Apostolic Church (Jetawi, Achrafieh, Beirut)

- Saint George (Sourp Kevork) Armenian Apostolic Church (Hadjin, Mar Mikhael, Beirut)

- Armenian Apostolic Church of the Assumption (Khalil Badaoui, Beirut)

- Armenian Apostolic Church of the Assumption (Jounieh, Kesrouan, Lebanon)

- Forty Martyrs (Karasoun Manoug) Armenian Apostolic Church (Marash, Bourj Hammoud)

- Holy Mother of God (Sourp Asdvadzadzin) Armenian Apostolic Church (Adana, Bourj Hammoud)

- Saint Vartan Armenian Apostolic Church (Tiro, Bourj Hammoud)

- Saint Sarkis Armenian Apostolic Church (Sis, Bourj Hammoud)

- Saint Paul (Sourp Boghos) Armenian Apostolic Church (Anjar, Beqaa, Lebanon)

- Holy Pentecost Armenian Apostolic Church (Tripoli, North Lebanon)

- Holy Mother of God (Sourp Asdvadzadzin) Armenian Apostolic Church – a complex that also includes the Zarehian Tebrevank (both in Bickfaya, Metn) and the commemorative statue of the Armenian genocide

Catholic Armenians[edit]

Armenian Catholic Church, has its patriarchate in the Lebanese capital Beirut, and represents Armenian Catholics around the world. Armenian Catholic Church also has its summer residence and its convent in Bzoummar, Lebanon.

Armenian Catholic churches include:

- St. Elie-St. Gregory the Illuminator (Sourp Yeghia – Sourp Krikor Lousavoritch Armenian Catholic Cathedral, (Debbas Square, Downtown Beirut)

- Armenian Catholic Church of the Annunciation (Achrafieh, Jetawi, Beirut) – also serving as church for the Armenian Catholic Patriarchal Eparchy.

- Armenian Catholic Church and the Convent of Bzoummar (Bzommar, Lebanon)

- St. Saviour (Sourp Pergitch) Armenian Catholic Church (Bourj Hammoud)

- Holy Cross (Sourp Khatch) Armenian Catholic Church (Zalka)

- Our Lady of Fatima Armenian Catholic Church (Hoch el Zaraani, Zahle, Beqaa)

- Our Lady of the Rosary Armenian Catholic Church (Anjar, Beqaa)

Evangelical Armenians[edit]

Armenian Evangelical Church, headquartered in Ashrafieh. The affairs of the Lebanese Evangelical community is run by the Union of the Union of the Armenian Evangelical Churches in the Near East (UAECNE).

Major Armenian Evangelical Churches:

- First Armenian Evangelical Church (Kantari, Beirut)

- Armenian Evangelical Church (Achrafieh, Beirut)

- Armenian Evangelical Church (Nor Marash, Bourj Hammoud)

- Armenian Evangelical Emmanuel Church (Nor Amanos, Baouchriye)

- Armenian Evangelical Church (Anjar, Beqaa)

The Armenian Evangelical Church has 5 active youth groups called "Chanits" which is a part of the World's Christian Endeavor Union.[36] Children's, teenagers', and Chanits camps; women's conferences, church retreats, and educational programs take place at "KCHAG" which is located just outside Beirut in Mansouriyeh, Matn District. There are also a number of "Brethren" churches of Evangelical orientation ("Yeghpayroutyoun" in Armenian). [citation needed]

Monuments[edit]

Armenian Genocide Monument[edit]

Bikfaya is home to a commemorative plaque and monumental sculpture, honoring the victims of the 1915 Armenian genocide. Designed by Zaven Khedeshian and renovated by Hovsep Khacherian in 1993, the outdoor, freestanding sculpture rests on top of a hill that is located on the grounds of the summer retreat of the Catholicate of Cilicia.

The sculpture is a bronze abstract figure of a woman standing with hands open toward the sky. A plaque with Arabic and Armenian inscriptions reads:

This monument, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Armenian genocide, was erected with the cooperation of the whole Armenian Community in Lebanon, to celebrate the rebirth of the Armenian nation and to express gratitude to our country, Lebanon – April 24, 1969

Members of the Armenian community of Lebanon visit the monument on April 24 every other year. The pilgrimages are alternated with the memorial chapel at the Armenian Catholicossate in Antelias.[37]

Sports and Scouts Movements[edit]

There are three predominantly Armenian sports clubs in Lebanon with a strong tradition in sports as well as Scouting. They are

- Homenetmen Beirut also known as HMEM—full name Hay Marmnagertagan Enthanour Miyutioun (Armenian General Union of Physical Culture)

- Homenmen Beirut also known as HMM—full name Hay Marzagan Miyutioun (Armenian Sports Union)

- Antranik Sports Club (of the Armenian Youth Association (AYA) of the Armenian General Benevolent Union AGBU)

All of them have various branches distributed in many Lebanese cities throughout the country where there are Lebanese Armenian communities. [citation needed]

Football[edit]

The Armenian clubs Homenetmen and Homenmen have important football teams in the official first and second division football leagues in Lebanon, although the membership of the teams is not restricted to ethnic Armenians and will usually include other Lebanese non-Armenian players as well as contracted foreign players, including professional players from Armenia.

Homenetmen Beirut has won the Lebanese Football Championship title 7 times in the years: 1944, 1946, 1948, 1951, 1955, 1963 and 1969 and Homenmen Beirut the Championship title 4 times in 1945, 1954, 1957 and 1961. Overall, both clubs feature in the top 5 of most titles in Lebanese football with Homenetmen Beirut winning seven Lebanese titles and Homenmen 4 titles.

Pagramian Sports Club was active with its football program in the 1940s and 1950s until it closure in 1960. In 1969, a new sports club Ararad Sports Association considered as a continuation of Pagramian's sports programme.

Basketball[edit]

Armenian clubs Antranik and Homenetmen have prominent basketball teams playing in the official first and second division basketball league in Lebanon, although the membership of the teams is mixed and is not restricted to Armenians and will usually include other Lebanese non-Armenian players as well as contracted foreign players. Many Lebanese Armenians have represented Lebanon in the national team. In women's sports, the Armenian basketball clubs (Homenetmen and Antranik) are traditionally considered as powerhouses in the sport, and both clubs have won the official Lebanese Basketball Championships women title on several occasions. The Armenian club Antranik's Women Basketball team went on to win the pan-Arab club championship titles. [citation needed]

Other Sports[edit]

The above-mentioned Lebanese Armenian clubs also have huge influence on many other sports in Lebanon, but most notably in cycling, table tennis (ping pong) and track and fields. Individual Armenians have also excelled, most notably in weightlifting, wrestling and martial arts competitions. [citation needed]

Women Sports[edit]

Lebanese Armenians also have great influence in women sports in Lebanon, most notably in basketball, cycling and table tennis. The Armenian basketball clubs of Homenetmen and Antranik have won the official Lebanese Basketball Championships on several occasions. The Armenian club Antranik's Women Basketball team went on to win the pan-Arab championship titles. Homenetmen Antelias' Women Basketball team won the Lebanese championship consecutively twice in 2016 and 2017.[38][39]

Notable people[edit]

Lebanon knows a great number of Armenian notable personalities including politicians Khatchig Babikian, Karim Pakradouni, Hagop Pakradounian, and Vartine Ohanian, media personalities like Zaven Kouyoumdjian, Paula Yacoubian, Nshan Der Haroutioutian, and Mariam Nour, sportsmen like Gretta Taslakian and Wartan Ghazarian, and artists like Paul Guiragossian, Pierre Chammassian, Serj Tankian, Ara Malikian, John Dolmaian, Lazzaro (producer), C-rouge.

See also[edit]

- Armenia–Lebanon relations

- Armenian diaspora

- Armenians in the Middle East

- Armenian Revolutionary Federation in Lebanon

- Anjar, Lebanon

- Bourj Hammoud

- Holy See of Cilicia

- List of Lebanese Armenians

- Lebanese Canadian

- Lebanese American

Sources[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Lebanon Minorities Overview Archived February 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Armenians born, raised in Lebanon still have command of Turkish language". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

He said that nearly 70% of Armenians in Lebanon can speak Turkish, adding that the new generation also learned Turkish thanks to Turkish soap operas.

- ^ جدلية, Jadaliyya-. "The Legacy of Turkish in the Armenian Diaspora". Jadaliyya – جدلية. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

Turkish was certainly at its strongest among Armenians in the early years of the diaspora, but by no means have the second, third, or fourth generations completely lost touch with the language. Turkish is firmly implanted in the colloquial Western Armenian spoken among descendants of Ottoman Armenians from both Turkish- and Armenian-speaking families. Mixing in Turkish is still so commonplace in conversation that it is a great compliment to be known to speak makour [clean] Armenian.

- ^ "Armenians, Kurds in Lebanon hold on to their languages | Samar Kadi". AW. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

When Armenians first arrived in Lebanon [fleeing genocide in Turkey], they spoke their native language in addition to the Turkish language. Eventually the third generation lost the Turkish, replacing it with Arabic

- ^ "PATTERNS OF LANGUAGE USE AMONG ARMENIANS IN BEIRUT". studylib.net. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ^ a b Harris, William W. (2015). Lebanon: A History, 600-2011. Studies in Middle Eastern history. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-19-518111-1.

- ^ a b c How The Lebanese-Armenian Community Thrived Over Decades, by Hussein Yassine, July 2020

- ^ The Armenians of Lebanon, by S. Varjabedian, Beirut, 1951, p. 5-8

- ^ a b c Lebanese Armenians; A Distingtive Community in the Armenian Diaspora and in Lebanese Society, by Scott Abramson, p. 213

- ^ "Gorup 194".

- ^ Migliorino, Nicola. Constructing Armenia in Lebanon and Syria: Ethno-Cultural Diversity, page 166

- ^ Armenians in Lebanon, UNHCR, 1989

- ^ Rev. James Karnusian, retired pastor and one of three persons to establish ASALA, dies in Switzerland // The Armenian Reporter International, 18 April 1998.

- ^ "Kevork Ajemian, Prominent Contemporary Writer and Surviving Member of Triumvirate Which Founded ASALA, Dies in Beirut, Lebanon", Armenian Reporter, 1999-02-01

- ^ "Political Interest Groups", Turkey: A Country Study ed. Helen Chapin Metz. Washington, D.C.: The Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, 283, 354–355 OCLC 17841957

- ^ "Lebanon Recognizes the Armenian Genocide". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ Another Armenian dies in Beirut blast, News.am

- ^ At least three Armenians killed in deadly Beirut blasts, Panarmenian.net

- ^ Armenian Catholicosate damaged in Beirut explosion, Public Radio of Armenia, 05.08.20

- ^ Armenian representative in Lebanon: The scale of destruction from Beirut blast is unprecedented

- ^ "The cultural cradle for Lebanon's Armenians". Retrieved 2018-11-21.

- ^ "Armenian Community Center". Facebook.

- ^ "A.R.F Hohita Keri Gomide". Facebook.

- ^ "Birds Nest Orphanage".

- ^ "Armenian protest against Erdogan visit turns violent". Azad-Hye.com. 3 December 2010. Retrieved 28 June 2013.{

- ^ Agadjanian, Alexander (2016-04-15). Armenian Christianity Today: Identity Politics and Popular Practice. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-17856-9.

- ^ a b c Alajaji, Sylvia Angelique (2015). "BEIRUT: 1932–1958". In Sylvia Angelique Alajaji (ed.). Music and the Armenian Diaspora. Searching for Home in Exile. Indiana University Press. pp. 82–106. ISBN 978-0-253-01755-0. JSTOR j.ctt16xwbgf.9.

- ^ a b c Migliorino, Nicola (2008). (Re)constructing Armenia in Lebanon and Syria: Ethno-cultural Diversity and the State in the Aftermath of a Refugee Crisis. Berghahn Books. pp. 125–167. ISBN 978-1-84545-352-7.

- ^ a b c "Tribute: Actor and Director Fazlian Played Important Role in Armenian and Lebanese Theater". The Armenian Mirror-Spectator. 2016-02-25. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

- ^ "Kasbar Ipegian Theater Company". Hamazkayin. 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

- ^ Manoukian, Jennifer (2014-07-25). "The Child of a Refugee". The Armenian Weekly. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

- ^ "Al-Raida" (65–75). The Institute. 1994.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rowe, Victoria (2003). A History of Armenian Women's Writing, 1880-1922. Cambridge Scholars Press. ISBN 978-1-904303-23-7.

- ^ a b Nucho, Joanne Randa (2016-11-22). Everyday Sectarianism in Urban Lebanon: Infrastructures, Public Services, and Power. Princeton University Press. pp. 75–78. ISBN 978-1-4008-8300-4.

- ^ a b Hovannisian, Richard G. (1974). "The Ebb and Flow of the Armenian Minority in the Arab Middle East". Middle East Journal. 28 (1): 19–32. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4325183.

- ^ "World's Christian Endeavor Union".

- ^ Monument in Bikfaya, Lebanon

- ^ "Homenetmen Antelias wins Lebanese Women Basketball Championship". Horizon. 2016-06-14. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ^ "Homenetmen Ladies Retain the Women's League Title Sports 961". sports-961.com. 2017-05-19. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

External links[edit]

- Religion

- Media

- Other