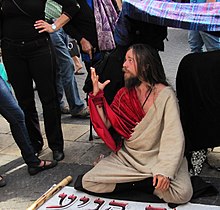

Jerusalem syndrome is a group of mental phenomena involving the presence of religiously themed ideas, or experiences that are triggered by a visit to the city of Jerusalem. It is not endemic to one single religion or denomination but has affected Jews, Christians, and Muslims of many different backgrounds. It is not listed as a recognised condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or the International Classification of Diseases.

The best known, although not the most prevalent, manifestation of Jerusalem syndrome (classified as Type III) is the phenomenon whereby a person who seems previously balanced and devoid of any signs of psychopathology becomes psychotic after arriving in Jerusalem.[not verified in body] The psychosis is characterised by an intense religious theme and typically resolves to full recovery after a few weeks or after being removed from the area. The religious focus of Jerusalem syndrome distinguishes it from other phenomena, such as Stendhal syndrome in Florence or Paris syndrome in Paris.

In a 2000 article in the British Journal of Psychiatry, Bar-El et al. claim to have identified and described a specific syndrome which emerges in tourists with no previous psychiatric history.[1] However, this claim has been disputed by M. Kalian and E. Witztum.[2][3] Kalian and Witztum stressed that nearly all of the tourists who demonstrated the described behaviours were mentally ill prior to their arrival in Jerusalem. They further noted that, of the small proportion of tourists alleged to have exhibited spontaneous psychosis after arrival in Jerusalem, Bar-El et al. had presented no evidence that the tourists had been well prior to their arrival in the city.

History[edit]

Jerusalem syndrome has previously been regarded as a form of hysteria, referred to as "fièvre Jérusalemienne".[4] It was first clinically described in the 1930s by Jerusalem psychiatrist Heinz Hermann, one of the founders of modern psychiatric research in Israel.[5] Whether or not these behaviors specifically arise from visiting Jerusalem is debated, as similar behaviors have been noted at other places of religious and historical importance such as Mecca and Rome (see Stendhal syndrome). It is known that cases of the syndrome had already been observed during the Middle Ages, since it was described in the itinerary of Felix Fabri and the biography of Margery Kempe.[citation needed] Other cases were described in the vast literature of visitors to Jerusalem during the 19th century.

Bar-El et al. suggested that at the approach of the year 2000, large numbers of otherwise normal visitors might be affected by a combination of their presence in Jerusalem and the religious significance of the millennium, causing a massive increase in the numbers of Jerusalem syndrome admissions to hospital. Despite a slight increase in tourist hospitalisations with the rise in total tourism to Jerusalem during the year 2000, the feared epidemic of Jerusalem syndrome never materialised.[1]

Types[edit]

The classic Jerusalem syndrome, where a visit to Jerusalem seems to trigger an intense religious psychosis that resolves quickly after or on departure, has been a subject of debate in the medical literature.[2][3][6] Most of the discussion has centered on whether this definition of the Jerusalem syndrome is a distinct form of psychosis, or simply a re-expression of a previously existing psychotic illness that was not picked up by the medical authorities in Israel.

In response to this, Bar-El et al. classified the syndrome[1] into three major types to reflect the different types of interactions between a visit to Jerusalem and unusual or psychosis-related thought processes. However, Kalian and Witztum have objected, saying that Bar-El et al. presented no evidence to justify the detailed typology and prognosis presented and that the types in fact seem to be unrelated rather than different aspects of a syndrome.

Type I[edit]

Jerusalem syndrome imposed on a previous psychotic illness. This refers to individuals already diagnosed as having a psychotic illness before their visit to Jerusalem. They have typically gone to the city because of the influence of religious ideas, often with a goal or mission in mind that they believe needs to be completed on arrival or during their stay. For example, affected persons may believe themselves to be important historical religious figures or may be influenced by important religious ideas or concepts (such as causing the coming of the Messiah or the second coming of Christ).

Type II[edit]

Jerusalem syndrome superimposed on and complicated by idiosyncratic ideas. This does not necessarily take the form of mental illness and may simply be a culturally anomalous obsession with the significance of Jerusalem, either as an individual, or as part of a small religious group with idiosyncratic spiritual beliefs.

Type III[edit]

Jerusalem syndrome as a discrete form, uncompounded by previous mental illness. This describes the best-known type, whereby a previously mentally balanced person becomes psychotic after arriving in Jerusalem. It can include a paranoid belief that an agency is after the individual, causing their symptoms of psychosis through poisoning and medicating.[7]

Bar-El et al. reported 42 such cases over a period of 13 years, but in no case were they able to actually confirm that the condition was temporary.

Prevalence[edit]

During a period of 13 years (1980–1993) for which admissions to the Kfar Shaul Mental Health Center in Jerusalem were analysed, it was reported[1] that 1,200 tourists with severe, Jerusalem-themed mental problems were referred to this clinic. Of these, 470 were admitted to hospital. On average, 100 such tourists have been seen annually, 40 of them requiring admission to hospital. About three and a half million tourists visit Jerusalem each year. Kalian and Witztum note that as a proportion of the total numbers of tourists visiting the city, this is not significantly different from any other city.[2][8]

In popular culture[edit]

"The Jerusalem Syndrome", a theater play by Joshua Sobol, deals with the fanaticism that led the destruction of the Jewish Second Temple.[9]

In The X-Files (Season 3, Episode 11, "Revelations", released in 1995), the perpetrator is depicted as having "Jerusalem Syndrome" after a visit to the city. He returns to the US and goes on to kill a child who has signs of stigmata.

The 2001 song "Jerusalem" was composed by James Raymond on the topic of the Jerusalem Syndrome. It appears on the 2001 record Just Like Gravity, by CPR (David Crosby, Jeff Pevar, James Raymond).

In The Simpsons 2010 episode "The Greatest Story Ever D'ohed", Homer develops Jerusalem syndrome while visiting Israel with his family as part of a tour group from Springfield. The illness and its effects on him become a central element of the episode's plot. Eventually, most members of the tour group are overcome with Jerusalem syndrome, each one proclaiming that he/she is the messiah.[10]

In the 2014 ABC series Black Box, the episode "Jerusalem" (Season 1, Episode 5) features a character diagnosed with Jerusalem syndrome after he becomes suddenly and compulsively religious during a trip to Israel.[11]

The 2015 movie Jeruzalem features a character that is suspected to have the Jerusalem syndrome.[12]

"Jerusalem", the twelfth story in Neil Gaiman's 2015 collection, Trigger Warning, centres around a British woman who comes down with the syndrome on holiday. She believes God is speaking to her and eventually flees her home to return to Jerusalem.[13]

The catalog of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's 2016 show about an earlier era of the city's history used the syndrome as the "organizing metaphor" for the first paragraph of the introduction, per a review.[14]

In 2023 the York Theatre Company produced "The Jerusalem Syndrome,"[15] a musical comedy written by Kyle Rosen, Laurence Holzman and Felicia Needleman, and directed by Don Stephenson. The 14-person cast included Farah Alvin and Lenny Wolpe.

See also[edit]

- Culture shock

- Foolishness for Christ

- List of messiah claimants

- Messiah complex

- Paris syndrome

- Religion and schizophrenia

- Religious delusion

- Stendhal syndrome

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Bar-el Y, Durst R, Katz G, Zislin J, Strauss Z, Knobler HY. (2000) Jerusalem syndrome. British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 86–90. Full text Archived 2008-05-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Kalian M, Witztum E. (2000) "Comments on Jerusalem syndrome". British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 492. Full text Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kalian M, Witztum E. (1999) "The Jerusalem syndrome—fantasy and reality a survey of accounts from the 19th and 20th centuries." Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat Sci., 36(4):260–71. Abstract Archived 2017-12-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Elon, Amos.Jerusalem, City of Mirrors. Little, Brown, 1989, p. 147. ISBN 978-0-316-23388-0

- ^ The Jerusalem Syndrome in Biblical Archaeology Archived 2012-01-14 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Fastovsky N, Teitelbaum A, Zislin J, Katz G, Durst R. (2000) Jerusalem syndrome or paranoid schizophrenia? Psychiatric Services, 51 (11), 1454. Full text Archived 2021-11-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fastovsky, Natasha; Teitelbaum, Alexander; Zislin, Josef; Katz, Gregory; Durst, Rimona (August 2000). "The Jerusalem Syndrome". Psychiatric Services. 51 (8): 1052–a–1052. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.51.8.1052-a. PMID 10913469.

- ^ Tannock C, Turner T. (1995) Psychiatric tourism is overloading London beds. BMJ 1995;311:806 Full Text Archived 2006-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Jerusalem Syndrome / Joshua Sobol at Israeli Dramatists Website. Accessed 6 Nov 2023.

- ^ Saner, Emine (2018-01-16). "What is Jerusalem syndrome?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2018-05-21. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- ^ "Jerusalem". IMDb. Archived from the original on 2021-11-06. Retrieved 2018-10-28.

- ^ "Jeruzalem". IMDb. Archived from the original on 2019-10-16. Retrieved 2019-11-09.

- ^ O'Hehir, Andrew (2015-03-08). "Neil Gaiman's 'Trigger Warning'". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2020-08-29. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- ^ Namdar, Ruby, "400 Years of Jerusalem Culture" Archived 2016-12-08 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times, December 2, 2016. The catalogue is titled Jerusalem: 1000-1400: Every People Under Heaven, edited by Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ JerusalemSyndromeMusical.com

Further reading[edit]

- Kalian, M.; Catinari, S.; Heresco-Levi, U.; Witztum, E. "Spiritual Starvation in a holy space – a form of Jerusalem Syndrome", Mental Health, Religion & Culture 11(2): 161–172, 2008.

- Kalian, M.; Witztum, E. "Facing a Holy Space: Psychiatric hospitalization of tourists in Jerusalem". In: Kedar, Z.B.; Werblowsky, R.J., Eds.: Sacred Space: Shrine, City, Land. MacMillan and The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1998.

- Kalian, M.; Witztum. E. "Jerusalem Syndrome as reflected in the pilgrimage and biographies of four extraordinary women from the 14th century to the end of the 2nd Millennium". Mental Health, Religion and Culture 5, 2002.

- Van der Haven, A. "The holy fool still speaks. The Jerusalem Syndrome as a religious subculture". In: Mayer, T.; Mourad, S.A., Eds.: Jerusalem. Idea and Reality. Routledge, 2008, pp. 103–122.

- Witztum, E.; Kalian, M. "The Quest for redemption: Reality and Fantasy in the Mission to Jerusalem". In: Hare, P.A.; and Kressel, G.M., Eds.: Israel as Center Stage. Bergin and Garvy, 2001.

- Witztum E., Kalian M., "Overwhelmed by spirituality in Jerusalem" in "Emotion in Motion" - Tourism, Affect and Transformation. Edited by David Picard and Mike Robinson. Ashgate, UK. 2012.

- Kalian M., Witztum E., "The Management of Pilgrims with Malevolent Behaviour in a Holy Space: A Study of Jerusalem Syndrome" in Lappkari M., Griffin K., Eds. "Pilgrimage and Tourism to Holy Cities, Ideological and Management Perspectives" CABI International, 2016, 100–113.

- Brian F., Allison F., "Me and My Wife Mary Magdalene", Living With Spousal Jerusalem Syndrome, Portland Publishing 2021, 93–98.

- Justin M, "Dreaming of Jerusalem" A Journey To The Past, Coast Publishing Group 2021, 109-115

External links[edit]

- Article from Project X Magazine

- Ravitz, Jessica. "Homer Simpson isn't the only would-be 'Messiah' in Jerusalem". CNN. March 29, 2010.