The history of nicotine marketing stretches back centuries. Nicotine marketing has continually developed new techniques in response to historical circumstances, societal and technological change, and regulation. Counter marketing has also changed, in both message and commonness, over the decades, often in response to pro-nicotine marketing.

Pre-1800[edit]

The coughing, throat irritation, and shortness of breath caused by smoking are obvious, and tobacco was criticized as unhealthy long before the invention of the clinical study. In A Counterblaste to Tobacco (1604), James VI of Scotland and I of England described smoking as "A custome lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse", and urged his subjects not to use tobacco.[1] In the 1600s, many countries banned its use.[2] Pope Urban VIII issued a 1624 papal bull condemning tobacco and making its use in holy places punishable by excommunication;[3] Pope Benedict XIII repealed the ban one hundred years later.[4]

1800–1880[edit]

The first known nicotine advertisement in the United States was for the snuff and tobacco products and was placed in the New York daily paper in 1789. At the time, American tobacco markets were local. Consumers would generally request tobacco by quality, not brand name, until after the 1840s.[5]

Many European tobacco bans were repealed during the Revolutions of 1848.

Cigarettes were first made in Seville, from cigar scraps. British soldiers took up the habit during the Crimean War (1853–1856).[2] The American Civil War in the early 1860s also led to increased demand for tobacco from American soldiers, and in non-tobacco-growing regions.[2]

Public health measures against chewing tobacco (spitting, especially other than in a spitoon, spread diseases such as flu and tuberculosis) increased cigarette consumption.[2]

After the development of color lithography in the late 1870s, collectible picture series were printed onto cigarette cards, previously only used to stiffen the packaging.[5]

In 1913, a cigarette brand was advertised nationally for the first time in the US. RJ Reynolds advertised it as milder than competing cigarettes.[6]

Mass production and temperance, 1880–1914[edit]

Pre-rolled cigarettes, like cigars, were initially expensive, as a skilled cigarette roller could produce only about four cigarettes per minute on average[7] Cigarette-making machines were developed in the 1880s, replacing hand-rolling.[8] One early machine could roll 120,000 cigarettes in 10 hours, or 200 a minute.[7][9][10] Mass production revolutionized the cigarette industry.[11] Cigarette companies began to reckon production in millions of cigarettes per day.[5]

Higher production and cheaper cigarettes gave companies an incentive to increase consumption. By the last quarter of the 19th century, magazines carried advertisements for different brands of cigarettes, snuff, and pipe tobacco.[8] Demand for cigarettes rose exponentially, ~doubling every five years in Canada and the US (until demand began to rise even faster, ~tripling during the four years of World War I).[2]: 429, Fig.1

Anti-tobacco movements[edit]

In the late 1800s, the temperance movement was strongly involved in anti-tobacco campaigns, and particularly with the prevention of youth smoking. They argued that smoking was addictive, unhealthy, stunted the growth of children, and, in women, was harmful during pregnancy.[12]

By 1890, 26 American states had banned sales to minors. Over the next decade, further restrictions were legislated, including prohibitions on sale; measures were widely circumvented, for instance by selling expensive matches and giving away cigarettes with them, so there were further bans on giving out free samples of cigarettes.[2]

After women won the vote in the early 1900s, temperance groups successfully campaigned for Juvenile Smoking Laws throughout Australia. At this time, most adults there smoked pipes, and cigarettes were used only by juveniles.[12]

1914–1950[edit]

World War I[edit]

Free or subsidized branded cigarettes were distributed to troops during World War I.[8] Demand for cigarettes in North America, which had been roughly doubling every five years, began to rise even faster, now approximately tripling during the four years of war.[2]: 429, Fig.1

In the face of imminent violent death, the health harms of cigarettes became less of a concern, and there was public support for drives to get cigarettes to the front lines.[12] Billions of cigarettes were distributed to soldiers in Europe by national governments, the YMCA, the Salvation Army, and the Red Cross. Private individuals also donated money to send cigarettes to the front, even from jurisdictions where the sale of cigarettes was illegal. Not giving soldiers cigarettes was seen as unpatriotic.[2]

Interwar[edit]

By the time the war was over, a generation had grown up, and a large proportion of adults smoked, making anti-smoking campaigns substantially more difficult.[12] Returning soldiers continued to smoke, making smoking more socially acceptable. Temperance groups began to concentrate their efforts on alcohol.[12] By 1927, American states had repealed all their anti-smoking laws, except those on minors.[2]

Modern advertising was created with the innovative techniques used in tobacco advertising beginning in the 1920s.[14][15]

Advertising in the interwar period consisted primarily of full page, color magazine and newspaper advertisements. Many companies created slogans for their brand and used celebrity endorsements from famous men and women. Some advertisements contained fictional doctors reassuring customers that their specific brand was good for health.[16]

Smoking was also widely seen in films, possibly due to paid product placement .

In 1924, menthol cigarettes were invented,[17] but they were not initially popular, remaining at a few percent of market share until marketing in the fifties.[18]: 35–37

In the 1920s, tobacco companies continued to target women, aiming to increase the number of smokers.[19] At first, in light of the threat of tobacco prohibition from temperance unions, marketing was subtle; it indirectly and deniably suggested that women smoked. Testimonials from smoking female celebrities were used. Ads were designed to "prey on female insecurities about weight and diet", encouraging smoking as a healthy alternative to eating sweets.[20]

Campaigns used the traditional association that smoking was improper for women to advantage. They marketed cigarettes as "Torches of Freedom", and made a dependence-inducing drug a symbol of women's independence. Lung cancer rates in women rose sharply.[21]

In 1929 Edward Bernays, commissioned by the American Tobacco Company to get more women smoking, decided to hire women to smoke their "torches of freedom" as they walked in the Easter Sunday Parade in New York. He was very careful when picking women to march because "while they should be good looking, they should not look too model-y" and he hired his own photographers to make sure that good pictures were taken and then published around the world.[22]

In 1929, the Sturmabteilung, the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, founded a cigarette company as a way to raise funds and make itself less financially dependent on the party leadership. SA members were expected to smoke only SA brands.[23] There is evidence that coercion was used to promote the sale of these cigarettes. Through this scheme, a typical SA unit earned hundreds of Reichsmarks each month.[24] The brand also promoted political ideas, being sold with collectible image sets showing historical army uniforms.[25]

Medical concerns[edit]

Of course it is perfectly easy to give up smoking. One would not like to think that one has become such a slave to tobacco that one cannot do without it—a drug which weakens the heart, damages the nerves, gives you cancer and catarrh and so on. Personally I have given up smoking repeatedly.

"On Giving Up Smoking". Punch or The London Charivari. London. 1934-11-07. p. 506.; this was an old joke even in 1934[26]

Skyrocketing European lung cancer rates drew attention from doctors in the twenties and thirties.[27] Lung cancer had been a vanishingly rare disease. Before 1900, there were only 140 documented cases worldwide.[28] Then, suddenly, lung cancer became a leading cause of death in many countries (a status it retains to this day).[28][29]: 4 [better source needed]

Initially, suspicion was cast on causes including road tar, car exhaust, the 1918 flu pandemic, racial mixing, and the use of chemical weapons in World War I. However, in 1929, a statistical analysis strongly linking lung cancer to smoking was published by Fritz Lickint of Dresden. He did a retrospective cohort study showing that those with lung cancer were, disproportionately, smokers. He also found that men got lung cancer at several times the rate of women, and that, in countries where more women smoked, the difference was much smaller.[28] In 1932, a study in Poland came to the same conclusion, pointing out that the geographic and gender patterns of Polish lung cancer deaths matched those of smoking, but no other suggested cause, such as industry or cars (rare in Poland at the time).[28]

The medical community was criticized for its slow response to these findings. One 1932 paper attributed the slow response to smoking being common among doctors, as well as the general population.[27] Some temperance activists had continued to attack tobacco as expensive, addictive, and leading to petty theft. In the thirties, they also began to publicize the medical findings.[12] There was popular awareness these dangers of smoking (see accompanying quote).

World War II[edit]

Despite these findings, free and subsidized branded cigarettes were distributed to soldiers (on both sides) during World War II.[8][30]

Cigarettes were included in American soldiers' K-rations and C-rations, since many tobacco companies sent the soldiers cigarettes for free. Cigarette sales reached an all-time high at this point, as cigarette companies were not only able to get soldiers addicted, but specific brands also found a new loyal group of customers as soldiers who smoked their cigarettes returned from the war.[31]

A faction of the Nazi Party opposed tobacco use.[30] The Institute for Tobacco Hazards Research was founded. Some of those working with it were involved in mass murder and unethical medical experiments, and killed themselves at the end of the war, including Karl Astel, the head of the institute. The institute and other organizations directed anti-smoking campaigns at both the general public and doctors. Campaigns included pamphlets, reprints of academic articles and books, and smoking bans in many public places;[28] bans were, however, widely ignored.[30] An industry-funded counter-institute, the Tabacologia medicinalis, was shut down by Leonardo Conti.[28] Restrictions on cigarette advertising were enacted. After 1941, the Nazi party restricted anti-tobacco research and campaigns, for instance ordering the private anti-tobacco magazine Reine Luft to moderate its tone and submit all materials for censorship before publication.[30]

Tobacco companies continue to exploit associations with Nazis to fight anti-tobacco measures. Modern Germany has some of Europe's least restrictive tobacco control policies,[28] and more Germans both smoke and die of it in consequence.[32][33]

1950–70[edit]

Until the 1970s, most tobacco advertising was legal in the United States and most European nations. In the 1940s and 50s, tobacco was a major radio sponsor; in the 1950s and 60s, they became predominantly involved in television.[29]: 100 In the United States, in the 1950s and 1960s, cigarette brands frequently sponsored television shows—notably To Tell the Truth and I've Got a Secret. Brand jingles were commonly used on radio and television. Major cigarette companies would advertise their brands in popular TV shows such as The Flintstones and The Beverly Hillbillies, which were watched by many children and teens.[34] In 1964, after facing much pressure from the public, The Cigarette Advertising Code was created by the tobacco companies, which prohibited advertising directed to youth.[35]

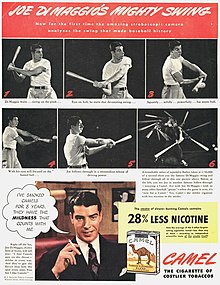

Advertising continued to use celebrities and famous athletes. Popular comedian Bob Hope was used to advertise for cigarette companies.[35] The African-American magazine Ebony often used athletes to advertise major cigarette brands.[36]

The nicotine industry also promoted "modified risk" nicotine products, falsely implied to be less harmful, such as roasted, "filter", menthol, and ventilated ("light") cigarettes.[37][38] These products were used to discourage quitting, by offering unwilling smokers an alternative to quitting, and implying that using the alternate product would reduce the hazards of smoking.[18]: 62–65 [29] "Modified risk" products also attract new smokers.[37]

It is now known that these products are not less harmful. Filter cigarettes became near-universal, but smokers suffered just as much illness and death.[39] Initially, efforts were made to develop filters that actually reduced harms; as it became obvious that this was not economically possible, filters were instead designed to turn brown with use.[40][41] Light cigarettes became so popular that, as of 2004, half of American smokers preferred them over regular cigarettes,[42] According to The Federal Government's National Cancer Institute (NCI), light cigarettes provide no benefit to smokers' health.[43][44] There is no evidence that menthol cigarettes are healthier, but there is evidence that they are somewhat easier to become addicted to and harder to quit.[18]: 25–27

Racial marketing strategies changed during the fifties, with more attention paid to racial market segmentation. The civil rights movement lead to the rise of African-American publications, such as Ebony. This helped tobacco companies to target separate marketing messages by race.[29]: 57 Tobacco companies supported civil rights organizations, and advertised their support heavily. Industry motives were, according to their public statements, to support civil rights causes; according to an independent review of internal tobacco industry documents, they were "to increase African American tobacco use, to use African Americans as a frontline force to defend industry policy positions, and to defuse tobacco control efforts". There had been internal resistance to tobacco sponsorship, and some organizations are now rejecting nicotine funding as a matter of policy.[45]

Race-specific advertising exacerbated small (a few percent) racial differences in menthol cigarette product preferences into large (tens of percent) ones.[46] Menthol cigarettes are somewhat more addictive,[18] and it has been argued that race-specific marketing for a more addictive product is a social injustice.[47][48]

Despite it being illegal at the time, tobacco marketers gave out free cigarette samples to children in black neighbourhoods in the U.S.[49] Similar practices continue in parts of the world; a 2016 study found over 12% of South African students had been given free cigarettes by tobacco company representative, with lower rates in five other subsaharan countries.[50] Worldwide, 1 in 10 children had been offered free cigarettes by a tobacco company representative, according to a 2000-2007 survey.[51]

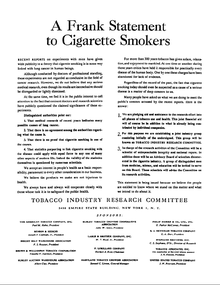

In 1954, tobacco companies ran the ad "A Frank Statement." The ad was the first in a disinformation campaign, disputing reports that smoking cigarettes could cause lung cancer and had other dangerous health effects.[52] It also referred to "research of recent years",[52] although solid statistical evidence of a link between smoking and lung cancer had first been published 25 years earlier.[28]

Prior to 1964, many of the cigarette companies advertised their brand by claiming that their product did not have serious health risks. A couple of examples would be "Play safe with Philip Morris" and "More doctors smoke Camels". Such claims were made both to increase the sales of their product and to combat the increasing public knowledge of smoking's negative health effects.[35] A 1953 industry document claims that the survey brand preference among doctors was done on doctors entering a conference, and asked (among a great many camouflage questions) what brand they had on them; marketers had previously placed packs of their Camels in doctors' hotel rooms before the doctors arrived,[53] which probably biassed the results.

In 1964, Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service was published. It was based on over 7,000 scientific articles that linked tobacco use with cancer and other diseases. This report led to laws requiring warning labels on tobacco products and to restrictions on tobacco advertisements. As these began to come into force, tobacco marketing became more subtle (for instance, the Joe Camel campaign resulted in increased awareness and uptake of smoking among children).[54] However, restrictions did have an effect on adult quit rates, with its use declining to the point that by 2004, nearly half of all Americans who had ever smoked had quit.[55]

Reaching the Black market in the United States[edit]

Historian Keith Wailoo argues the cigarette industry targeted a new market in the black audience starting in the 1960s. It took advantage of several converging trends. First was the increased national attention on the dangers of lung cancer. Cigarette companies took the initiative in fighting back. they developed menthol-flavored brands like Kool, which seemed to be more soothing to the throat, and advertised these as good for your health. A second trend was the Federal ban on tobacco advertising on radio and television. There was no ban on advertising in the print media, so the industry responded by large scale advertising in Black newspapers and magazines. They erecting billboards in inner city neighborhoods. The third trend was the Civil rights movement of the 1960s. Big Tobacco responded by investing heavily in the Civil Rights Movement, winning the gratitude of many national and local leaders. Menthol flavored cigarette brands systematically sponsored local events in the black community, and subsidized major black organizations especially the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). They also subsidized many churches and schools. The marketing initiative was a success as the rate of smoking in the black community grew, while it declined among whites, Furthermore three or four black smokers purchased menthol cigarettes.[56]

Post-advertising-restrictions; 1970 and later[edit]

The period after nicotine advertising restrictions were brought in is characterised by ingenious circumvention of progressively stricter regulations. The industry continued to dispute medical research: denying, for instance, that nicotine was addictive, while deliberately spiking their cigarettes with additional nicotine to make them more addictive.[16]

Advertising restrictions typically shift advertising spending to unrestricted media. Banned on television, ads move to print; banned in all conventional media, ads shift to sponsorships; banned as in-store advertising and packaging, advertising shifts to shill (undisclosed) marketing reps, sponsored online content, viral marketing, and other stealth marketing techniques.[29]: 272–280

Another method of evading restrictions is to sell less-regulated nicotine products instead of the ones for which advertising is more regulated. For instance, while TV ads of cigarettes are banned in the United States, similar TV ads of e-cigarettes are not.[58]

The most effective media are usually banned first, meaning advertisers need to spend more money to addict the same number of people.[29]: 272 Comprehensive bans can make it impossible to effectively substitute other forms of advertising, leading to actual falls in consumption.[29]: 272–280 However, skillful use of allowed media can increase advertising exposure; the exposure of U.S. children to nicotine advertising is increasing as of 2018.[58]

In the US, sport and event sponsorships and billboards became important in the 1970s and 80s, due to TV and radio advertising bans. Sponsors benefit from placing their advertising at sporting events, naming events after themselves, and recruiting political support from sporting agencies. In the 1980s and 90s, these sponsorships were banned in the US and many other countries. Spending has since shifted to point-of-sale advertising and promotional allowances (where legal), direct mail advertising, and Internet advertising. Stealth marketing is also becoming more common,[29]: 100 partly to offset mistrust of the tobacco industry.[29]: Ch.6&7

One major Indian company gives annual bravery awards in its own name; some recipients have rejected or returned them.[59]

Nicotine use is frequently shown in movies. While academics had long speculated that there was paid product placement, it was not until internal industry documents were released that there was hard evidence of such practices.[29]: 363–364 The documents show that in the 1980s and 1990s, cigarettes were shown in return for ≤six-figure (US$) sponsorship deals. More money was paid for a star actor to be shown using nicotine. While this sponsorship is now banned in some countries, it is unclear whether the bans are effective, as such deals are generally not publicized or investigated.[29]: 401

Smokers in movies are generally healthier, more successful, and more racially privileged than actual smokers. Health effects, including coughing and addiction, are shown or mentioned in only a few percent of cases, and are less likely to be mentioned in films targeted at younger viewers.[29]: 372–374

In the nineties, internet access expanded in many countries; the web is a major medium for nicotine advertising.

Both Google and Microsoft have policies that prohibit the promotion of tobacco products on their advertising networks.[60][61] However, some tobacco retailers are able to circumvent these policies. On Facebook, unpaid content, created and sponsored by tobacco companies, is widely used to advertise nicotine-containing products, with photos of the products, "buy now" buttons and a lack of age restrictions, in contravention of ineffectively enforced Facebook policies.[62][63][64][failed verification]

In 1998, the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement was reached between the then four largest United States tobacco companies Philip Morris (now Altria), R. J. Reynolds, Brown & Williamson and Lorillard.

21st century[edit]

In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration wrote a major review of menthol cigarettes, which are somewhat more addictive and no healthier than regular cigarettes.[18] It was subsequently proposed that they should be banned, partially on grounds that race-specific marketing for a more addictive product is racist.[47]

See also[edit]

Gallery[edit]

-

1900 cigarette ad

-

1916 ad showing a fictional doctor endorsing a cigar brand[65]

-

1918 advertisement for "Turkish" cigarettes

-

1921 cigar ad claiming that a fictional doctor called this brand "harmless" and "never gets on your nerves" (a term then used for nicotine withdrawal symptoms)

-

In a 1922 ad, a small child, smoking a cigarette, tells his amused parents not to worry, as he is smoking for a veteran's charity. Children were often used in early cigarette ads, where they helped normalize smoking as part of family living, and gave associations of purity, vibrancy, and life.[66]

-

"We claim no curative powers for Phillip Morris" say this 1943 ad, in the small text.

-

Women in the War cigarette ad showing a woman signalling civilian aircraft. The ad associates taking a "man's job" with smoking cigarettes like a man: "Co-ed leaves Campus to fill a Man's job. She's "in the service"—even to her choice of cigarettes..."

-

Tobacco display in a store Munich in 2008

-

Cigarette commercial, New Zealand, 1925

-

Lucky Strike cigarette commercial

-

Muriel cigars commercial.

References[edit]

- ^ A Counterblaste to Tobacco (retrieved February 22, 2008) Quote: A custome lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Alston, Lee J.; Dupré, Ruth; Nonnenmacher, Tomas (2002). "Social reformers and regulation: the prohibition of cigarettes in the United States and Canada" (PDF). Explorations in Economic History. 39 (4): 425–445. doi:10.1016/s0014-4983(02)00005-0.

- ^ Gately, Iain (2001). Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-8021-3960-3.

- ^ Cutler, Abigail. "The Ashtray of History", The Atlantic Monthly, January/February 2007.

- ^ a b c More About Tobacco Advertising and the Tobacco Collections. Scriptorium.lib.duke.edu.

- ^ Kozlowski, L T; O'Connor, R J (2002). "Cigarette filter ventilation is a defective design because of misleading taste, bigger puffs, and blocked vents". Tobacco Control. 11 (Suppl 1): I40–50. doi:10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i40. PMC 1766061. PMID 11893814.

- ^ a b Bonsack's cigarette machine Archived 2006-11-13 at the Wayback Machine. URL last accessed 2006-10-11.

- ^ a b c d James, Randy (2009-06-15). "A Brief History Of Cigarette Advertising". TIME. Archived from the original on September 21, 2011. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ^ U.S. patent 238,640 Archived 2017-11-07 at the Wayback Machine, with diagrams. URL last accessed 2006-10-11.

- ^ U.S. patent 247,795 Archived 2017-11-07 at the Wayback Machine, with diagrams. URL last accessed 2006-10-11

- ^ Bennett, W.: The Cigarette Century[permanent dead link], Science 80, September/October 1980. URL last accessed 2006-10-11.

- ^ a b c d e f "The anti-tobacco reform and the temperance movement in Australia: connections and differences. - Free Online Library". Retrieved 2018-05-19.

- ^ "Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising". tobacco.stanford.edu.

- ^ Donald G. Gifford (2010) Suing the Tobacco and Lead Pigment Industries, p.15 quotation:

...during the early twentieth century, tobacco manufacturers virtually created the modern advertising and marketing industry as it is known today.

- ^ Stanton Glantz in Mad Men Season 3 Extra – Clearing the Air – The History of Cigarette Advertising, part 1, min 3:38 quotation:

...development of modern advertising. And it was really the tobacco industry, from the beginning, that was at the forefront of the development of modern, innovative, advertising techniques.

- ^ a b Markel, Howard (2007-03-20). "Tracing the Cigarette's Path From Sexy to Deadly". The New York Times.

- ^ "Process of Treating Cigarette Tobacco". United States Patent Office.

- ^ a b c d e Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC) of the Center for Tobacco Products of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (2011-07-21). Menthol Cigarettes and Public Health: Review of the Scientific Evidence and Recommendations (PDF). US Food and Drug Administration. p. 252. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-17. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ Statement: Surgeon General's Report on Women and Tobacco Underscores Need for Congress to Grant FDA Authority Over Tobacco (Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids) Archived 2005-02-05 at the Wayback Machine. Tobaccofreekids.org.

- ^ "Targeting women: Mass marketing begins, Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising". Retrieved 2018-05-19.

As the threat of tobacco prohibition from temperance unions settled down in the late 1920s, tobacco companies became bolder with their approach to targeting women through advertisements, openly targeting women in an attempt to broaden their market and increase sales. The late 1920s saw the beginnings of major mass marketing campaigns designed specifically to target women. Cigarette manufacturers have for a long time subtly suggested in some of their advertising that women smoked, a New York Times article from 1927 reveals. But Chesterfield s 1927 Blow some my way campaign was transparent to the public even at the time of printing, and soon after, the campaigns became less and less subtle. In 1928, Lucky Strike introduced its Cream of the Crop campaign, featuring celebrity testimonials from female smokers, and then followed with Reach for a Lucky Instead of a Sweet in 1929, designed to prey on female insecurities about weight and diet. As the decade turned, many cigarette brands came out of the woodwork and joined in on unabashedly targeting women by illustrating women smoking, rather than hinting at it.

- ^ "Targeting women:Let's Smoke Girls, Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising". Retrieved 2018-05-19.

Before the First World War, smoking was associated with the loose morals of prostitutes and wayward women. Clever marketers managed to turn this around in the 1920s and 1930s, latching onto women s liberation movements and transforming cigarettes into symbols of women's independence. In 1929, as part of this effort, the American Tobacco Company organized marches of women carrying Torches of Freedom (i.e., cigarettes) down New York s 5th Avenue to emphasize their emancipation. The tobacco industry also sponsored training sessions to teach women how to smoke, and competitions for most delicate smoker. Many of the advertisements targeting women throughout the decades have concentrated on women s empowerment. Early examples include I wish I were a man so I could smoke (Velvet, 1912), while later examples like You ve come a long way baby (Virginia Slims) were more clearly exploitive of the Women s Liberation Movement. It is interesting to note that the Marlboro brand, famous for its macho Marlboro Man, was for decades a woman s cigarette (Mild as May with Ivory tips to protect the lips) before it underwent an abrupt sex change in 1954. Only 5 percent of American women smoked in 1923 versus 12 percent in 1932 and 33 percent in 1965 (the peak year). Lung cancer was still a rare disease for women in the 1950s, though by the year 2000 it was killing nearly 70,000 women per year. Cancer of the lung surpassed breast cancer as the leading cause of cancer death among women in 1987.

- ^ Brandt, Allan M. (2007). The Cigarette Century. New York: Basic Books, pp. 84-85.

- ^ Robert N. Proctor, The Nazi War on Cancer, pp. 234–237.

- ^ Thomas D. Grant, Stormtroopers and Crisis in the Nazi Movement, p. 102.

- ^ Joyce Goodman and Jane Martin, Gender, Colonialism and Education, p. 81.

- ^ "It's Easy to Quit Smoking. I've Done It a Thousand Times – Quote Investigator". quoteinvestigator.com. 19 September 2012.

- ^ a b Rolleston, J. D (1932). "The Cigarette Habit". Addiction. 30 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1932.tb04849.x. OCLC 79886767. S2CID 72586449.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Proctor, Robert N. (2001-02-01). "Commentary: Schairer and Schöniger's forgotten tobacco epidemiology and the Nazi quest for racial purity". International Journal of Epidemiology. 30 (1): 31–34. doi:10.1093/ije/30.1.31. PMID 11171846. Retrieved 2018-05-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Davis, Ronald M.; Gilpin, Elizabeth A.; Loken, Barbara; Viswanath, K.; Wakefield, Melanie A. (2008). The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use (PDF). National Cancer Institute tobacco control monograph series. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. p. 684.

- ^ a b c d Bachinger, Eleonore; McKee, Martin; Gilmore, Anna (May 2008). "Tobacco policies in Nazi Germany: not as simple as it seems". Public Health. 122 (5): 497–505. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2007.08.005. ISSN 0033-3506. PMC 2441844. PMID 18222506.

- ^ See "1943 - 290 billion smokes supplied or sold"

- ^ Zigarettenwerbung in Deutschland – Marketing für ein gesundheitsgefährdendes Produkt (PDF). Rote Reihe: Tabakprävention und Tabakkontrolle. Heidelberg: Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum. 2012. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- ^ Dr. Annette Bornhäuser; Dr. med. Martina Pötschke-Langer (2001). Factsheet Tabakwerbeverbot (PDF). Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- ^ Pollay, Richard W (1994). "Promises, promises: Self-regulation of US cigarette broadcast advertising in the 1960s". Tobacco Control. 3 (2): 134–44. doi:10.1136/tc.3.2.134. JSTOR 20207023. PMC 1759332.

- ^ a b c Richards, J. W.; Tye, J. B.; Fischer, P. M. (1996). "The tobacco industry's code of advertising in the United States: myth and reality" (PDF). Tobacco Control. 5 (4): 297. doi:10.1136/tc.5.4.295. JSTOR 20207231. PMC 1759528. PMID 9130364.

- ^ Pollay, Richard W; Lee, Jung S; Carter-Whitney, David (1992). "Separate, but Not Equal: Racial Segmentation in Cigarette Advertising". Journal of Advertising. 21 (1): 45–57. doi:10.1080/00913367.1992.10673359. JSTOR 4188824. S2CID 143438525.

- ^ a b Mallock N, Böss L, Burk R, Danziger M, Welsch T, Hahn H, Trieu HL, Hahn J, Pieper E, Henkler-Stephani F, Hutzler C, Luch A (June 2018). "Levels of selected analytes in the emissions of "heat not burn" tobacco products that are relevant to assess human health risks". Archives of Toxicology. 92 (6): 2145–2149. doi:10.1007/s00204-018-2215-y. PMC 6002459. PMID 29730817.

- ^ El-Toukhy S, Baig SA, Jeong M, Byron MJ, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT (August 2018). "Impact of modified risk tobacco product claims on beliefs of US adults and adolescents". Tobacco Control. 27 (Suppl 1): tobaccocontrol–2018–054315. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054315. PMC 6202195. PMID 30158212.

- ^ Harris, Bradford (2011-05-01). "The intractable cigarette 'filter problem'". Tobacco Control. 20 (Suppl 1): –10–i16. doi:10.1136/tc.2010.040113. eISSN 1468-3318. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 3088411. PMID 21504917.

- ^ Kennedy P (2012-07-06). "Who Made That Cigarette Filter?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ^ Harris B (May 2011). "The intractable cigarette 'filter problem'". Tobacco Control. 20 Suppl 1 (Suppl_1): i10–6. doi:10.1136/tc.2010.040113. PMC 3088411. PMID 21504917.

- ^ Light but just as deadly, by Peter Lavelle. The Pulse, 21 October 2004.

- ^ The Truth About "Light" Cigarettes: Questions and Answers, from the National Cancer Institute factsheet

- ^ 'Safer' cigarette myth goes up in smoke, by Andy Coghlan. New Scientist, 2004

- ^ Yerger, V B; Malone, R. E (2002). "African American leadership groups: Smoking with the enemy". Tobacco Control. 11 (4): 336–45. doi:10.1136/tc.11.4.336. PMC 1747674. PMID 12432159.

- ^ Edwards, Jim (January 5, 2011). "Why Big Tobacco Targeted Blacks With Ads for Menthol Cigarettes". CBS News. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ a b Tavernise, Sabrina (2016-09-13). "Black Health Experts Renew Fight Against Menthol Cigarettes". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ https://blackdoctor.org/507006/african-american-tobacco-control-leadership-council-to-president-obama-give-our-community-a-fighting-chance/[full citation needed]

- ^ "Cigarette Suit Says Maker Gave Samples To Children". The New York Times. Associated Press. 2004-06-27. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ Chandora, Rachna; Song, Yang; Chaussard, Martine; Palipudi, Krishna Mohan; Lee, Kyung Ah; Ramanandraibe, Nivo; Asma, Samira; GYTS collaborative group (October 2016). "Youth access to cigarettes in six sub-Saharan African countries". Preventive Medicine. 91S: S23–S27. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.01.018. PMID 26845374.

- ^ Warren, C. W; Jones, N. R; Peruga, A; Chauvin, J; Baptiste, J. P; Costa De Silva, V; El Awa, F; Tsouros, A; Rahman, K; Fishburn, B; Bettcher, D. W; Asma, S; Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (2008). "Global youth tobacco surveillance, 2000-2007". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 57 (1): 1–28. PMID 18219269.

- ^ a b Daily Doc: TI, Jan 4, 1954: The 'Frank Statement' of 1954 Archived February 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Tobacco.org. 30 September 2000. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ^ "Untitled Document". tobacco.stanford.edu.[permanent dead link]

- ^ While D, Kelly S, Huang W, Charlton A (17 August 1996). "Cigarette advertising and onset of smoking in children: questionnaire survey". BMJ. 313 (7054): 398–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7054.398. PMC 2351819. PMID 8761227.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (November 2005). "Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2004". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 54 (44): 1121–4. PMID 16280969.

- ^ Keith Wailoo, Pushing Cool: Big Tobacco, Racial Marketing, and the Untold Story of the Menthol Cigarette (2021) excerpt

- ^ Gilpin, Elizabeth A; White, Martha M; Messer, Karen; Pierce, John P (2007). "Receptivity to Tobacco Advertising and Promotions Among Young Adolescents as a Predictor of Established Smoking in Young Adulthood". American Journal of Public Health. 97 (8): 1489–95. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.070359. PMC 1931446. PMID 17600271.

- ^ a b "More U.S. teens seeing e-cigarette ads". Business Insider. Reuters. Archived from the original on 2018-07-05. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ "Vivek Oberoi returns award". The Hindu. April 1, 2005. Archived from the original on April 6, 2005. Retrieved 2013-11-10.

- ^ Advertising.microsoft.com Archived 2010-08-26 at the Wayback Machine. Advertising.microsoft.com (28 September 2011).

- ^ Adwords.google.com. Adwords.google.com.

- ^ Welch, Ashley (April 5, 2018). "Facebook is used to promote tobacco, despite policies against it, study finds". CBS News. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ Jeter Hansen, Amy (17 July 2015). "Tobacco products promoted on Facebook despite policies". News Center. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ Hansen, Amy Jeter (2018-04-05). "Despite policies, tobacco products marketed on Facebook, Stanford researchers find". Scope. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ "Untitled Document". Archived from the original on 2018-05-25. Retrieved 2018-09-04.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-05-21. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)[full citation needed]

Further reading[edit]

- Alston, Lee J. et al. "Social reformers and regulation: the prohibition of cigarettes in the United States and Canada" Explorations in Economic History (2002) . 39 (4): 425–445. doi:10.1016/s0014-4983(02)00005-0.

- Brandt, Allan M. The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, And Deadly Persistence Of The Product That Defined America (Basic Books, 2007)

- Corti, Count. A history of smoking (1931, Bracken reprint 1996) online, covers Europe

- Fine, Gary Alan. "The Psychology of Cigarette Advertising: Professional Puffery" Journal of Popular Culture 8#2 (1974), pp. 153-166.

- Gately, Iain. Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization (Simon & Schuster, 2001).

- Goodman, Jordan. Tobacco in history: The cultures of dependence (Routledge, 2005), world history; online.

- Goodman, Jordan. Tobacco in history and culture: an encyclopedia (Facts on File, 2005).

- Harrald, Chris, and Fletcher Watkins. The cigarette book: the history and culture of smoking (Skyhorse Publishing Inc., 2010).

- Hirschfelder, Arlene B. Encyclopedia of Smoking and Tobacco (Oryx Press, 1999).

- Joseph, Anne M. et al. "The Cigarette Manufacturers’ Efforts to Promote Tobacco to the U.S. Military." Military Medicine (2005) 170 (10): 874–880. doi:10.7205/MILMED.170.10.874. PMID 16435763

- Kluger, Richard. Ashes to Ashes: America's Hundred-Year Cigarette War, the Public Health, and the Unabashed Triumph of Philip Morris (Vintage, 1997) online

- Lohof, Bruce A. "The Higher Meaning of Marlboro Cigarettes" Journal of Popular Culture, (Winter 1969) 3#4

- Oreskes, Naomi, and Erik M. Conway. Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming (Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2011).

- Richards, J. W.; Tye, J. B.; Fischer, P. M. "The tobacco industry's code of advertising in the United States: myth and reality" Tobacco Control (1996). 5 (4): 297. doi:10.1136/tc.5.4.295. JSTOR 20207231. PMC 1759528. PMID 9130364

- Sobel, Robert. They Satisfy: The Cigarette in American Life (Anchor Books, 1978),

- White, Lawrence. Merchants of death: The American tobacco industry (1988).

- Whiteside, Thomas. Selling Death: Cigarette Advertising and Public Health (Liveright. 1971).

External links[edit]

- [https://famri.org/history-of-tobacco-military-rations/ "History of Tobacco Military Rations

and Efforts to Keep Troops Smoking" (FAMRI, 2020)]

![1916 ad showing a fictional doctor endorsing a cigar brand[65]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1e/Cigar_ad_yes_Im_a_doctor.jpg/151px-Cigar_ad_yes_Im_a_doctor.jpg)

![In a 1922 ad, a small child, smoking a cigarette, tells his amused parents not to worry, as he is smoking for a veteran's charity. Children were often used in early cigarette ads, where they helped normalize smoking as part of family living, and gave associations of purity, vibrancy, and life.[66]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7f/Small_child_smokes_for_charity.jpg/163px-Small_child_smokes_for_charity.jpg)