The history of neuraxial anaesthesia dates back to the late 1800s[1] and is closely intertwined with the development of anaesthesia in general.[2] Neuraxial anaesthesia, in particular, is a form of regional analgesia placed in or around the Central Nervous System, used for pain management and anaesthesia for certain surgeries and procedures.[3]

19th century[edit]

In 1855, Friedrich Gaedcke (1828–1890) became the first to chemically isolate cocaine, the most potent alkaloid of the coca plant. Gaedcke named the compound "erythroxyline".[4][5]

In 1884, Austrian ophthalmologist Karl Koller (1857–1944) instilled a 2% solution of cocaine into his own eye and tested its effectiveness as a local anesthetic by pricking the eye with needles.[6] His findings were presented a few weeks later at annual conference of the Heidelberg Ophthalmological Society.[7] The following year, William Halsted (1852–1922) performed the first brachial plexus block.[8] Also in 1885, James Leonard Corning (1855–1923) injected cocaine between the spinous processes of the lower lumbar vertebrae, first in a dog and then in a healthy man.[9][10] His experiments are the first published descriptions of the principle of neuraxial blockade.[11]

On August 16, 1898, German surgeon August Bier (1861–1949) performed surgery under spinal anesthesia in Kiel.[12] Following the publication of Bier's experiments in 1899, a controversy developed about whether Bier or Corning performed the first successful spinal anesthetic.[13][14]

There is no doubt that Corning's experiments preceded those of Bier. For many years however, a controversy centered around whether Corning's injection was a spinal or an epidural block. The dose of cocaine used by Corning was eight times higher than that used by Bier and Tuffier. Despite this much higher dose, the onset of analgesia in Corning's human subject was slower and the dermatomal level of ablation of sensation was lower. Also, Corning did not describe seeing the flow of cerebrospinal fluid in his reports, whereas both Bier and Tuffier did make these observations. Based on Corning's own description of his experiments, it is apparent that his injections were made into the epidural space, and not the subarachnoid space.[14] Finally, Corning was incorrect in his theory on the mechanism of action of cocaine on the spinal nerves and spinal cord. He proposed – mistakenly – that the cocaine was absorbed into the venous circulation and subsequently transported to the spinal cord.[14]

Although Bier properly deserves credit for the introduction of spinal anesthesia into the clinical practice of medicine, it was Corning who created the experimental conditions that ultimately led to the development of both spinal and epidural anesthesia.[14]

20th century[edit]

Romanian surgeon Nicolae Racoviceanu-Pitești (1860–1942) was the first to use opioids for intrathecal analgesia; he presented his experience in Paris in 1901.[15][16]

In 1921, Spanish military surgeon Fidel Pagés (1886–1923) developed the modern technique of lumbar epidural anesthesia,[17] which was popularized in the 1930s by Italian surgery professor Achille Mario Dogliotti (1897–1966).[16] Dogliotti is known for describing a "loss-of-resistance" technique, involving constant application of pressure to the plunger of a syringe to identify the epidural space whilst advancing the Tuohy needle – a technique sometimes referred to as Dogliotti's principle.[18] Eugen Bogdan Aburel (1899–1975) was a Romanian surgeon and obstetrician who in 1931 was the first to describe blocking the lumbar plexus during early labor, followed by a caudal epidural injection for the expulsion phase.[19][20]

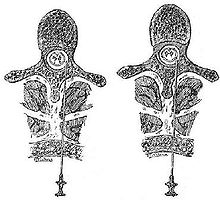

Beginning in October 1941, Robert Andrew Hingson (1913–1996), Waldo B. Edwards and James L. Southworth, working at the United States Marine Hospital at Stapleton, on Staten Island in New York, developed the technique of continuous caudal anesthesia.[21][22][23][24] Hingson and Southworth first used this technique in an operation to remove the varicose veins of a Scottish merchant seaman. Rather than removing the caudal needle after the injection as was customary, the two surgeons experimented with a continuous caudal infusion of local anesthetic. Hingson then collaborated with Edwards, the chief obstetrician at the Marine Hospital, to study the use of continuous caudal anesthesia for analgesia during childbirth. Hingson and Edwards studied the caudal region to determine where a needle could be placed to deliver anesthetic agents safely to the spinal nerves without injecting them into the cerebrospinal fluid.[23]

The first use of continuous caudal anesthesia in a laboring woman was on January 6, 1942, when the wife of a United States Coast Guard sailor was brought into the Marine Hospital for an emergency Caesarean section. Because the woman had rheumatic heart disease (heart failure following an episode of rheumatic fever during childhood), her doctors believed that she would not survive the stress of labor but they also felt that she would not tolerate general anesthesia due to her heart failure. With the use of continuous caudal anesthesia, the woman and her baby survived.[25]

The first described placement of a lumbar epidural catheter was performed by Manuel Martínez Curbelo (5 June 1906–1 May 1962) on January 13, 1947.[26][27] Curbelo, a Cuban anesthesiologist, introduced a 16 gauge Tuohy needle into the left flank of a 40-year-old woman with a large ovarian cyst. Through this needle, he introduced a 3.5 French ureteral catheter made of elastic silk into the lumbar epidural space. He then removed the needle, leaving the catheter in place and repeatedly injected 0.5% percaine (cinchocaine, also known as dibucaine) to achieve anesthesia. Curbelo presented his work on September 9, 1947, at the 22nd Joint Congress of the International Anesthesia Research Society and the International College of Anesthetists, in New York City.[20][28]

See also[edit]

- History of anatomy

- History of general anesthesia

- History of medicine

- History of neuroscience

- History of surgery

- History of tracheal intubation

- Local anesthesia

References[edit]

- ^ Mandabach, Mark G (2002-12-01). "The early history of spinal anesthesia". International Congress Series. The history of anesthesia. 1242: 163–168. doi:10.1016/S0531-5131(02)00783-5. ISSN 0531-5131.

- ^ Brill, S.; Gurman, G. M.; Fisher, A. (September 2003). "A history of neuraxial administration of local analgesics and opioids". European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 20 (9): 682–689. doi:10.1017/s026502150300111x. ISSN 0265-0215. PMID 12974588. S2CID 46735940.

- ^ Olawin, Abdulquadri M.; M Das, Joe (2023), "Spinal Anesthesia", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30725984, retrieved 2023-08-17

- ^ Gaedcke, F (1855). "Ueber das Erythroxylin, dargestellt aus den Blättern des in Südamerika cultivirten Strauches Erythroxylon Coca Lam". Archiv der Pharmazie. 132 (2): 141–50. doi:10.1002/ardp.18551320208. S2CID 86030231.

- ^ Zaunick, R (1956). "Early history of cocaine isolation: Domitzer pharmacist Friedrich Gaedcke (1828–1890); contribution to Mecklenburg pharmaceutical history". Beitr Gesch Pharm Ihrer Nachbargeb. 7 (2): 5–15. PMID 13395966.

- ^ Koller, K (1884). "Über die verwendung des kokains zur anästhesierung am auge" [On the use of cocaine for anesthesia on the eye]. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift (in German). 34: 1276–1309.

- ^ Karch, SB (2006). "Genies and furies". A brief history of cocaine from Inca monarchs to Cali cartels : 500 years of cocaine dealing (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 51–68. ISBN 978-0849397752.

- ^ Halsted, WS (1885-09-12). "Practical comments on the use and abuse of cocaine; suggested by its invariably successful employment in more than a thousand minor surgical operations". New York Medical Journal. 42: 294–5.

- ^ Corning, JL (1885). "Spinal anaesthesia and local medication of the cord". New York Medical Journal. 42: 483–5.

- ^ Corning, JL (1888). "A further contribution on local medication of the spinal cord, with cases". New York Medical Record: 291–3.

- ^ Gorelick, PB; Zych, D (1987). "James Leonard Corning and the early history of spinal puncture". Neurology. 37 (4): 672–4. doi:10.1212/WNL.37.4.672. PMID 3550521. S2CID 31624731.

- ^ Bier, A (1899). "Versuche uber cocainisirung des ruckenmarkes (Experiments on the cocainization of the spinal cord)". Deutsche Zeitschrift für Chirurgie (in German). 51 (3–4): 361–9. doi:10.1007/bf02792160. S2CID 41966814.

- ^ Wulf, HFW (1998). "The centennial of spinal anesthesia". Anesthesiology. 89 (2): 500–6. doi:10.1097/00000542-199808000-00028. PMID 9710410. S2CID 31186270.

- ^ a b c d Marx, GF (1994). "The first spinal anesthesia. Who deserves the laurels?". Regional Anesthesia. 19 (6): 429–30. PMID 7848956.

- ^ Brill, S; Gurman, GM; Fisher, A (2003). "A history of neuraxial administration of local analgesics and opioids". European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 20 (9): 682–9. doi:10.1017/S026502150300111X. ISSN 0265-0215. PMID 12974588. S2CID 46735940.

- ^ a b J. C. Diz, A. Franco, D. R. Bacon, J. Rupreht, and J. Alvarez (eds.); The history of anesthesia: proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium, Elsevier (2002), pp. 205–6, 0-444-51003-6

- ^ Pagés, F (1921). "Anestesia metamérica". Revista de Sanidad Militar (in Spanish). 11: 351–4.

- ^ Dogliotti, AM (1933). "Research and clinical observations on spinal anesthesia: with special reference to the peridural technique" (PDF). Anesthesia & Analgesia. 12 (2): 59–65. doi:10.1213/00000539-193301000-00014. S2CID 70731119.

- ^ Aburel, E (1931). "L'Anesthésie locale continue prolongée en obstétrique". Bull Soc Obst et Gyn de Paris (in French) (20): 35–37.

- ^ a b Aldrete, JA; Cabrera, H; Wright, AJ (2004). "Manuel Martinez Curbelo And Continuous Lumbar Epidural Anesthesia" (PDF). Bulletin of Anesthesia History. 22 (4): 1–8. doi:10.1016/S1522-8649(04)50045-8. PMID 20503747.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Edwards, WB; Hingson, RA (1942). "Continuous caudal anesthesia in obstetrics". American Journal of Surgery. 57 (3): 459–64. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(42)90599-3.

- ^ Hingson, RA; Edwards, WB (1942). "Continuous Caudal Anesthesia During Labor and Delivery". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 21: 301–11. doi:10.1213/00000539-194201000-00072.

- ^ a b Hingson, RA; Edwards, WB (1943). "Comprehensive review of continuous caudal analgesia for anesthetists". Anesthesiology. 4 (2): 181–96. doi:10.1097/00000542-194303000-00010. S2CID 73184705.

- ^ Rosenberg, H (1999). "Robert Andrew Hingson, M.D.: OB analgesia pioneer (1913–1996)". American Society of Anesthesiologists Newsletter. 63 (9): 12–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2014.

- ^ Hingson, RA; Edwards, WB (1943). "Continuous Caudal Analgesia in Obstetrics". Journal of the American Medical Association. 121 (4): 225–9. doi:10.1001/jama.1943.02840040001001.

- ^ "Dr. Pío Manuel Martínez Curbelo" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2014-05-28. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

- ^ Sainz Cabrera, Humberto; Aldrete Velazco, José Antonio; Vilaplana Santaló, Carlos (April 2007). "La anestesia epidural continua por via lumbar: antecedentes y descubrimiento". Rev Cub Anest Rean. (in Spanish). 6 (2): 1–18. Retrieved 5 April 2019 – via Biblioteca Virtual de Salud.

- ^ Martinez Curbelo, M (1949). "Continuous peridural segmental anesthesia by means of a ureteral catheter". Curr Res Anesth Analg. 28 (1): 13–23. doi:10.1213/00000539-194901000-00002. PMID 18105827.

Further reading[edit]

- Borgeat, A (2006). "All roads do not lead to Rome". Anesthesiology. 105 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1097/00000542-200607000-00002. PMID 16809983. S2CID 19403814.

- Crile, GW (1897). "Anesthesia of nerve roots with cocaine". Cleveland Medical Journal. 2: 355.

- Cushing, HW (1902). "I. On the Avoidance of Shock in Major Amputations by Cocainization of Large Nerve-Trunks Preliminary to their Division. With Observations on Blood-Pressure Changes in Surgical Cases". Annals of Surgery. 36 (3): 321–45. doi:10.1097/00000658-190209000-00001. PMC 1430733. PMID 17861171.

- de Pablo, JS; Diez-Mallo, J (1948). "Experience with Three Thousand Cases of Brachial Plexus Block: Its Dangers: Report of a Fatal Case". Annals of Surgery. 128 (5): 956–64. doi:10.1097/00000658-194811000-00008. PMC 1513923. PMID 17859253.

- Hirschel, G (1911-07-18). "Die anästhesierung des plexus brachialis fuer die operationen an der oberen extremitat" [Anesthesia of the brachial plexus for operations on the upper extremity]. Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift (in German). 58: 1555–6.

- Kulenkampff, D (1911). "Zur anästhesierung des plexus brachialis" [On anesthesia of the brachial plexus]. Zentralblatt für Chirurgie (in German). 38: 1337–40.

- Kulenkampff, D; Persky, MA (1928). "Brachial Plexus Anæsthesia". Annals of Surgery. 87 (6): 883–91. doi:10.1097/00000658-192806000-00015. PMC 1398572. PMID 17865904.

- Winnie, AP; Collins, VJ (1964). "The subclavian perivascular technique of brachial plexus anesthesia". Anesthesiology. 25 (3): 35–63. doi:10.1097/00000542-196405000-00014. PMID 14156576. S2CID 36275626.

External links[edit]

- Anesthesia as a specialty: Past, present and future Presentation by Prof. Janusz Andres.