| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

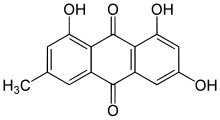

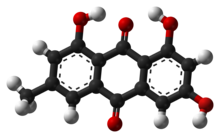

| Preferred IUPAC name

1,3,8-Trihydroxy-6-methylanthracene-9,10-dione | |

| Other names

6-Methyl-1,3,8-trihydroxyanthraquinone

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.509 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C15H10O5 | |

| Molar mass | 270.240 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Orange solid |

| Density | 1.583±0.06 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 256 to 257 °C (493 to 495 °F; 529 to 530 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Emodin (6-methyl-1,3,8-trihydroxyanthraquinone) is a chemical compound, of the anthraquinone family, that can be isolated from rhubarb, buckthorn, and Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica syn. Polygonum cuspidatum).[1] Emodin is particularly abundant in the roots of the Chinese rhubarb (Rheum palmatum), knotweed and knotgrass (Polygonum cuspidatum and multiflorum) as well as Hawaii ‘au‘auko‘i cassia seeds or coffee weed (Semen cassia).[2] It is specifically isolated from Rheum palmatum L.[3] It is also produced by many species of fungi, including members of the genera Aspergillus, Pyrenochaeta, and Pestalotiopsis, inter alia. The common name is derived from Rheum emodi, a taxonomic synonym of Rheum australe, (Himalayan rhubarb) and synonyms include emodol, frangula emodin, rheum emodin, 3-methyl-1,6,8-trihydroxyanthraquinone, Schüttgelb (Schuttgelb), and Persian Berry Lake.[4]

Pharmacology[edit]

Emodin is an active component of several plants used in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) such as Rheum palmatum, Polygonum cuspidatum and Polygonum multiflorum. It has various actions including laxative, antibacterial and antiinflammatory effects,[5][6] and has also been identified as having potential antiviral activity against coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV-2,[7][8] being one of the major active components of the antiviral TCM formulation Lianhua Qingwen.[9][10]

A computational study was conducted to investigate the inhibition mechanism on the formation of the Spike-ACE2 protein complex.[2] Specifically, it is seen dose-dependent inhibition in the prevention of infection by the SARS-Cov-1 whose evidence has stimulated further investigations on SARS-Cov-2.[2]

Emodin has been shown to inhibit the ion channel of protein 3a which could play a crucial role in the release of the virus from infected cells.[11]

List of species[edit]

The following plant species produce emodin:

- Acalypha australis[12]

- Cassia occidentalis[13]

- Cassia siamea[14]

- Frangula alnus[15]

- Glossostemon bruguieri[16]

- Kalimeris indica[17]

- Polygonum hypoleucum[18]

- Reynoutria japonica (syn. Fallopia japonica)[19] (syn. Polygonum cuspidatum[20])

- Rhamnus alnifolia, the alderleaf buckthorn[21]

- Rhamnus cathartica, the common buckthorn[21]

- Rheum palmatum[22]

- Rumex nepalensis[23]

- Senna obtusifolia[24] (syn. Cassia obtusifolia[25])

- Thielavia subthermophila[26]

- Ventilago madraspatana[27]

Emodin also occurs in variable amounts in members of the crustose lichen genus Catenarina.[28]

Compendial status[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Dorland's Medical Dictionary (1938)

- ^ a b c Dellafiora L, Dorne JL, Galaverna G, Dall'Asta C (2020). "Preventing the Interaction between Coronaviruses Spike Protein and Angiotensin I Converting Enzyme 2: An in Silico Mechanistic Case Study on Emodin as a Potential Model Compound". Applied Sciences. 10 (18): 6358. doi:10.3390/app10186358. S2CID 224994102.

- ^ Tsay HS, Shyur LF, Agrawal DC, Wu YC, Wang SY (3 November 2017). Medicinal Plants – Recent Advances in Research and Development. Singapore: Springer Singapore. p. 339. ISBN 978-981-10-5978-0.

- ^ CID 3220 from PubChem

- ^ Dong X, Fu J, Yin X, Cao S, Li X, Lin L, Ni J (August 2016). "Emodin: A Review of its Pharmacology, Toxicity and Pharmacokinetics". Phytotherapy Research. 30 (8): 1207–18. doi:10.1002/ptr.5631. PMC 7168079. PMID 27188216.

- ^ Monisha BA, Kumar N, Tiku AB (2016). "Emodin and Its Role in Chronic Diseases". Anti-inflammatory Nutraceuticals and Chronic Diseases. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 928. pp. 47–73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-41334-1_3. ISBN 978-3-319-41332-7. PMID 27671812.

- ^ Ho TY, Wu SL, Chen JC, Li CC, Hsiang CY (May 2007). "Emodin blocks the SARS coronavirus spike protein and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 interaction". Antiviral Research. 74 (2): 92–101. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.04.014. PMC 7114332. PMID 16730806.

- ^ Zhou Y, Hou Y, Shen J, Huang Y, Martin W, Cheng F (2020). "Network-based drug repurposing for novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2". Cell Discovery. 6: 14. doi:10.1038/s41421-020-0153-3. PMC 7073332. PMID 32194980.

- ^ Wang CH, Zhong Y, Zhang Y, Liu JP, Wang YF, Jia WN, et al. (February 2016). "A network analysis of the Chinese medicine Lianhua-Qingwen formula to identify its main effective components". Molecular BioSystems. 12 (2): 606–13. doi:10.1039/c5mb00448a. PMID 26687282.

- ^ Runfeng L, Yunlong H, Jicheng H, Weiqi P, Qinhai M, Yongxia S, et al. (June 2020). "Lianhuaqingwen exerts anti-viral and anti-inflammatory activity against novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)". Pharmacological Research. 156: 104761. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104761. PMC 7102548. PMID 32205232.

- ^ Schwarz S, Wang K, Yu W, Sun B, Schwarz W (April 2011). "Emodin inhibits current through SARS-associated coronavirus 3a protein". Antiviral Research. 90 (1): 64–9. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.02.008. PMC 7114100. PMID 21356245.

- ^ Wang XL, Yu KB, Peng SL (June 2008). "[Chemical constituents of aerial part of Acalypha australis]" [Chemical Constituents of Aerial Part of Acalypha australis]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi = Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi = China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica (in Chinese). 33 (12): 1415–7. PMID 18837345.

- ^ Yadav JP, Arya V, Yadav S, Panghal M, Kumar S, Dhankhar S (June 2010). "Cassia occidentalis L.: a review on its ethnobotany, phytochemical and pharmacological profile". Fitoterapia. 81 (4): 223–30. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2009.09.008. PMID 19796670.

- ^ Nsonde Ntandou GF, Banzouzi JT, Mbatchi B, Elion-Itou RD, Etou-Ossibi AW, Ramos S, et al. (January 2010). "Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of Cassia siamea Lam. stem bark extracts". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 127 (1): 108–11. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.040. PMID 19799981.

- ^ Kremer D, Kosalec I, Locatelli M, Epifano F, Genovese S, Carlucci G, Končić MZ (April 2012). "Anthraquinone profiles, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of Frangula rupestris (Scop.) Schur and Frangula alnus Mill. bark". Food Chemistry. 131 (4): 1174–1180. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.09.094.

- ^ Meselhy MR (August 2003). "Constituents from Moghat, the Roots of Glossostemon bruguieri (Desf.)". Molecules. 8 (8): 614–621. doi:10.3390/80800614. PMC 6146927.

- ^ Wang G, Wang GK, Liu JS, Yu B, Wang F, Liu JK (April 2010). "[Studies on the chemical constituents of Kalimeris indica]" [Studies on the Chemical Constituents of Kalimeris indica]. Zhong Yao Cai = Zhongyaocai = Journal of Chinese Medicinal Materials (in Chinese). 33 (4): 551–4. PMID 20845783.

- ^ Chao PM, Kuo YH, Lin YS, Chen CH, Chen SW, Kuo YH (April 2010). "The metabolic benefits of Polygonum hypoleucum Ohwi in HepG2 cells and Wistar rats under lipogenic stress" (PDF). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 58 (8): 5174–80. doi:10.1021/jf100046h. PMID 20230058.

- ^ "Reynoutria japonica (Polygonaceae)". Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases. U.S. Department of Agriculture.

- ^ Ban SH, Kwon YR, Pandit S, Lee YS, Yi HK, Jeon JG (January 2010). "Effects of a bio-assay guided fraction from Polygonum cuspidatum root on the viability, acid production and glucosyltranferase of mutans streptococci". Fitoterapia. 81 (1): 30–4. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2009.06.019. PMID 19616082.

- ^ a b Sacerdote AB, King RB (2014). "Direct Effects of an Invasive European Buckthorn Metabolite on Embryo Survival and Development in Xenopus laevis and Pseudacris triseriata" (PDF). Journal of Herpetology. 48 (1): 51–58. doi:10.1670/12-066. S2CID 62818226.

- ^ Liu A, Chen H, Wei W, Ye S, Liao W, Gong J, et al. (July 2011). "Antiproliferative and antimetastatic effects of emodin on human pancreatic cancer". Oncology Reports. 26 (1): 81–9. doi:10.3892/or.2011.1257. PMID 21491088.

- ^ Gautam R, Karkhile KV, Bhutani KK, Jachak SM (October 2010). "Anti-inflammatory, cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, COX-1 inhibitory, and free radical scavenging effects of Rumex nepalensis". Planta Medica. 76 (14): 1564–9. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1249779. PMID 20379952. S2CID 260253513.

- ^ "Senna obtusifolia (Fabaceae)". Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases. U.S. Department of Agriculture.

- ^ Yang YC, Lim MY, Lee HS (December 2003). "Emodin isolated from Cassia obtusifolia (Leguminosae) seed shows larvicidal activity against three mosquito species". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (26): 7629–31. doi:10.1021/jf034727t. PMID 14664519.

- ^ Kusari S, Zühlke S, Kosuth J, Cellárová E, Spiteller M (October 2009). "Light-independent metabolomics of endophytic Thielavia subthermophila provides insight into microbial hypericin biosynthesis". Journal of Natural Products. 72 (10): 1825–35. doi:10.1021/np9002977. PMID 19746917.

- ^ Ghosh S, Das Sarma M, Patra A, Hazra B (September 2010). "Anti-inflammatory and anticancer compounds isolated from Ventilago madraspatana Gaertn., Rubia cordifolia Linn. and Lantana camara Linn". The Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 62 (9): 1158–66. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.2010.01151.x. PMID 20796195. S2CID 25769269.

- ^ Søchting U, Søgaard MZ, Elix JA, Arup U, Elvebakk A, sancho LG (2014). "Catenarina (Teloschistaceae, Ascomycota), a new Southern Hemisphere genus with 7-chlorocatenarin". The Lichenologist. 46 (2): 175–187. doi:10.1017/s002428291300087x. S2CID 83906534.

- ^ The British Pharmacopoeia Secretariat (2009). "Index, BP 2009" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2010.