| Cerebellar hypoplasia | |

|---|---|

| |

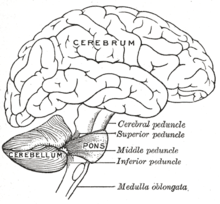

| Normal cerebellum (lower area) | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Cerebellar hypoplasia is characterized by reduced cerebellar volume, even though cerebellar shape is (near) normal. It consists of a heterogeneous group of disorders of cerebellar maldevelopment presenting as early-onset non–progressive congenital ataxia, hypotonia and motor learning disability.

Various causes have been incriminated, including hereditary, metabolic, toxic and viral agents. It was first reported by French neurologist Octave Crouzon in 1929.[1] In 1940, an unclaimed body came for dissection in London Hospital and was discovered to have no cerebellum. This unique case was appropriately named "human brain without a cerebellum" and was used every year in the Department of Anatomy at Cambridge University in a neuroscience course for medical students.[2]

Cerebellar hypoplasia can sometimes present alongside hypoplasia of the corpus callosum or pons. It can also be associated with hydrocephalus or an enlarged fourth ventricle; this is called Dandy–Walker malformation.[3]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Non-progressive early onset ataxia and poor motor learning are the most common presentation.[4]

Diagnosis[edit]

Magnetic resonance imaging[edit]

Three dimensional (3D) T2-weighted (T2w), axial, coronal, sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered appropriate for differentiation between gray matter and white matter acquisition of high-resolution anatomic information. T2w, axial and coronal imaging is more suitable for acquisition of high-resolution anatomic information and delineation of cortex, white matter, and gray matter nuclei. Diffusion tensor, axial imaging is used for evaluation of white matter microstructural integrity, identification of white matter tracts. CISS, axial + MPR imaging for evaluation of cerebellar folia, cranial nerves, ventricles, and foramina. Susceptibility weighted axial scans are employed for identification and characterization of hemorrhage, blood products, calcification, and iron accumulation.[5]

Classification[edit]

Classification systems for malformations of the cerebellum are varied and are constantly being revised as greater understanding of the underlying genetics and embryology of the disorders is uncovered. A classification proposed by Patel S in 2002[6] divides cerebellar malformations in two broad groups; those with cerebellar hypoplasia and; those with cerebellar dysplasia.[citation needed]

- I. Cerebellar hypoplasia

- A. Focal hypoplasia

- 1. Isolated vermis

- 2. One hemisphere hypoplasia

- B. Generalized hypoplasia

- 1. With enlarged fourth ventricle (“cyst,”), Dandy–Walker continuum

- 2. Normal fourth ventricle (no “cyst”)

- a. With normal pons

- b. With small pons i. Normal foliation

- a) Pontocerebellar hypoplasias of Barth, types I and II

- b) Cerebellar hypoplasias, not otherwise specified

- A. Focal hypoplasia

Treatment[edit]

There is no standard course of treatment for cerebellar hypoplasia. Treatment depends upon the underlying disorder and the severity of symptoms. Generally, treatment is symptomatic and supportive.[7] Balance rehabilitation techniques may benefit those experiencing difficulty with balance.[8] Therapies include physical, occupational, speech/language, visual, psychiatric/behavioral meds, and special education.[citation needed]

Prognosis[edit]

The prognosis of this developmental disorder is highly based on the underlying disorder. Cerebellar hypoplasia may be progressive or static in nature. Some cerebellar hypoplasia resulting from congenital brain abnormalities/malformations are not progressive. Progressive cerebellar hypoplasia is known for having poor prognosis, but in cases where this disorder is static, prognosis is better.[citation needed]

History[edit]

Following clinical report by Crouzon in 1929 Sarrouy reported two pairs of siblings with congenital cerebellar hypoplasia in 1958.[9] However pons, pyramidal tract and corpus callosum were also involved in these cases.[9] Wichman et al. in 1985 reported three sibling pairs with congenital cerebellar hypoplasia. "All six children presented in the first years of life with delays in motor and language development. All patients showed cerebellar and/or vermal dysfunction and, on formal psychometric testing, cognitive abilities ranged from normal to moderately retarded. Abnormalities on CT scan ranged from prominent valleculla to an enlarged cisterna magna with hypoplasia of the cerebellar hemispheres and vermis. The pedigrees are consistent with autosomal recessive inheritance."[4] Mathews KD, in 1989 also reported two cases of cerebellar hypoplasia in a family with unaffected parents suggestive of autosomal recessive inheritance.[10] The frequency and importance of the evaluation of the posterior fossa have increased significantly over the past 20 years owing to advances in neuroimaging with frequent reporting of posterior fossa malformation.[5]

References[edit]

- ^ Crouzon O (1929). "Atrophie cérébelleuse idiotique, in Études sur les Maladies Familiales Nerveuses et Dystrophiques". Paris: Masson: 90–111.

- ^ Lemon RN, Edgley SA (March 2010). "Life without a cerebellum". Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 133 (Pt 3): 652–4. doi:10.1093/brain/awq030. PMID 20305277.

- ^ Aldinger, Kimberly A.; Doherty, Dan (October 2016). "The genetics of cerebellar malformations". Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 21 (5): 321–332. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2016.04.008. ISSN 1744-165X. PMC 5035570. PMID 27160001.

- ^ a b Wichman A, Frank LM, Kelly TE (April 1985). "Autosomal recessive congenital cerebellar hypoplasia". Clinical Genetics. 27 (4): 373–82. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.1985.tb02279.x. PMID 3995786. S2CID 45397354.

- ^ a b Bosemani T, Orman G, Boltshauser E, Tekes A, Huisman TA, Poretti A (2015-02-01). "Congenital abnormalities of the posterior fossa". Radiographics. 35 (1): 200–20. doi:10.1148/rg.351140038. PMID 25590398.

- ^ Patel S, Barkovich AJ (August 2002). "Analysis and classification of cerebellar malformations". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 23 (7): 1074–87. PMC 8185716. PMID 12169461.

- ^ "Cerebellar Hypoplasia Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Archived from the original on 2015-01-04. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ^ "Cerebellar Hypoplasia". Sensory Learning. 7 March 2009. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009.

- ^ a b Sarrouy C, Raffi A, Boineau N (1957-01-01). "[2 Cases of cerebellar hypoplasia in the same family]". Archives Françaises de Pédiatrie. 14 (5): 449–60. PMID 13445326.

- ^ Mathews KD, Afifi AK, Hanson JW (July 1989). "Autosomal recessive cerebellar hypoplasia". Journal of Child Neurology. 4 (3): 189–94. doi:10.1177/088307388900400307. PMID 2768782. S2CID 33870941.

External links[edit]

- Cerebellar-Hypoplasia at NINDS

- Cerebellar hypoplasia at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases