| British Latin | |

|---|---|

| Region | Roman Britain, Sub-Roman Britain, Anglo-Saxon England |

| Extinct | Early Middle Ages |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

lat-bri | |

| Glottolog | None |

British Latin or British Vulgar Latin was the Vulgar Latin spoken in Great Britain in the Roman and sub-Roman periods. While Britain formed part of the Roman Empire, Latin became the principal language of the elite and in the urban areas of the more romanised south and east of the island. In the less romanised north and west it never substantially replaced the Brittonic language of the indigenous Britons. In recent years, scholars have debated the extent to which British Latin was distinguishable from its continental counterparts, which developed into the Romance languages.

After the end of Roman rule, Latin was displaced as a spoken language by Old English in most of what became England during the Anglo-Saxon settlement of the fifth and sixth centuries. It survived in the remaining Celtic regions of western Britain. However, it also died out in those regions by about 700; it was replaced by the local Brittonic languages.

Background[edit]

At the inception of Roman rule in AD 43, Great Britain was inhabited by the indigenous Britons, who spoke the Celtic language known as Brittonic.[1] Roman Britain lasted for nearly four hundred years until the early fifth century. For most of its history, it encompassed what was to become England and Wales as far north as Hadrian’s Wall, but with the addition, for shorter periods, of territories further north up to, but not including, the Scottish Highlands.[2]

Historians often refer to Roman Britain as comprising a "highland zone" to the north and west of the country and a "lowland zone" in the south and east,[3] with the latter being more thoroughly romanised[4] and having a Romano-British culture.[5] Particularly in the lowland zone, Latin became the language of most of the townspeople, of administration and the ruling class, the army and, following the introduction of Christianity, the church. Brittonic remained the language of the peasantry, which was the bulk of the population; members of the rural elite were probably bilingual.[6] In the highland zone, there were only limited attempts at Romanisation, and Brittonic always remained the dominant language.[7]

Throughout much of western Europe, from Late Antiquity, the Vulgar Latin of everyday speech developed into locally distinctive varieties which ultimately became the Romance languages.[8] However, after the end of Roman rule in Britain in the early 5th century, Vulgar Latin died out as an everyday spoken language.[9] The timing of its demise as a vernacular in Britain, its nature and its characteristics have been points of scholarly debate in recent years.

Sources of evidence[edit]

An inherent difficulty in evidencing Vulgar Latin is that as an extinct spoken language form, no source provides a direct account of it.[10] Reliance is on indirect sources of evidence such as "errors" in written texts and regional inscriptions.[11] They are held to be reflective of the everyday spoken language. Of particular linguistic value are private inscriptions made by ordinary people, such as epitaphs and votive offerings, and "curse tablets" (small metal sheets used in popular magic to curse people).[12]

In relation to Vulgar Latin specifically as it was spoken in Britain, Kenneth H. Jackson put forward in the 1950s what became the established view, which has only relatively recently been challenged.[13] Jackson drew conclusions about the nature of British Latin from examining Latin loanwords that had passed into the British Celtic languages.[14] From the 1970s John Mann, Eric P. Hamp and others used what Mann called "the sub-literary tradition" in inscriptions to identify spoken British Latin usage.[15]

In the 1980s, Colin Smith used stone inscriptions in particular in this way, although much of what Smith has written has become out of date as a result of the large number of Latin inscriptions found in Britain in recent years.[16] The best known of these are the Vindolanda tablets, the last two volumes of which were published in 1994 and 2003, but also include the Bath curse tablets, published in 1988, and other curse tablets found at a number of other sites throughout southern England from the 1990s onwards.[17]

Evidence of a distinctive language variety[edit]

Kenneth Jackson argued for a form of British Vulgar Latin, distinctive from continental Vulgar Latin.[18] In fact, he identified two forms of British Latin: a lower-class variety of the language not significantly different from Continental Vulgar Latin and a distinctive upper-class Vulgar Latin.[14] This latter variety, Jackson believed, could be distinguished from Continental Vulgar Latin by 12 distinct criteria.[18] In particular, he characterised it as a conservative, hypercorrect "school" Latin with a "sound-system [which] was very archaic by ordinary Continental standards".[19]

In recent years, research into British Latin has led to modification of Jackson's fundamental assumptions.[14] In particular, his identification of 12 distinctive criteria for upper-class British Latin has been severely criticised.[20] Nevertheless, although British Vulgar Latin was probably not substantially different from the Vulgar Latin of Gaul, over a period of 400 years of Roman rule, British Latin would almost certainly have developed distinctive traits.[21] That and the likely impact of the Brittonic substrate both mean that a specific British Vulgar Latin variety most probably developed.[21] However, if it did exist as a distinct dialect group, it has not survived extensively enough for diagnostic features to be detected, despite much new subliterary Latin being discovered in England in the 20th century.[22]

Extinction as a vernacular[edit]

It is not known when Vulgar Latin ceased to be spoken in Britain,[23] but it is likely that it continued to be widely spoken in various parts of Britain into the 5th century.[24] In the lowland zone, Vulgar Latin was replaced by Old English during the course of the 5th and the 6th centuries, but in the highland zone, it gave way to Brittonic languages such as Primitive Welsh and Cornish.[9] However, scholars have had a variety of views as to when exactly it died out as a vernacular. The question has been described as "one of the most vexing problems of the languages of early Britain."[25]

Lowland zone[edit]

In most of what was to become England, the Anglo-Saxon settlement and the consequent introduction of Old English appear to have caused the extinction of Vulgar Latin as a vernacular.[26] The Anglo-Saxons spread westward across Britain in the 5th century to the 7th century, leaving only Cornwall and Wales in the southern part of the country and the Hen Ogledd in the north under British rule.[27][28]

The demise of Vulgar Latin in the face of Anglo-Saxon settlement is very different from the fate of the language in other areas of Western Europe that were subject to Germanic migration, like France, Italy and Spain, where Latin and the Romance languages continued.[29] One theory is that in Britain there was a greater collapse in Roman institutions and infrastructure, leading to a much greater reduction in the status and prestige of the indigenous romanised culture; and so the indigenous people were more likely to abandon their languages in favour of the higher-status language of the Anglo-Saxons.[30] On the other hand, Richard Coates believes that the linguistic evidence points to the now little supported traditional view that there was a mass replacement of the population of southern and eastern England with Anglo-Saxon settlers. His view, based on place name evidence and the lack of loan words in English from Latin “with a Britonnic accent”, is that this is the most convincing explanation for the extinction of Latin (or Brittonic) in the lowland zone.[31]

From the fifth century, there are only occasional evidential hints of a continuing tradition of spoken Latin, and then only in Church contexts and among the educated.[24] Alaric Hall has speculated that Bede’s 8th century Ecclesiastical History of the English People may contain indications that spoken British Latin had survived as a vernacular in some form to Bede’s time. The evidence relied on is the use of a word with a possible preserved British vulgar Latin spelling (Garmani for Germani) as well as onomastic references.[34]

Highland zone[edit]

Before Roman rule ended, Brittonic had remained the dominant language in the highland zone.[7] However, the speakers of Vulgar Latin were significantly but temporarily boosted in the 5th century by the influx of Romano-Britons from the lowland zone who were fleeing the Anglo-Saxons.[35] These refugees are traditionally characterised as being "upper class" and "upper middle class".[36] Certainly, Vulgar Latin maintained a higher social status than Brittonic in the highland zone in the 6th century.[37]

Although Latin continued to be spoken by many of the British elite in western Britain,[38] by about 700, it had died out.[39] The incoming Latin-speakers from the lowland zone seem to have rapidly assimilated with the existing population and adopted Brittonic.[35] The continued viability of British Latin may have been negatively affected by the loss to Old English of the areas where it had been strongest: the Anglo-Saxon conquest of the lowland zone may have indirectly ensured that Vulgar Latin would not survive in the highland zone either.[40]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Koch 2006, pp. 291–292.

- ^ Black 2017, pp. 6–10.

- ^ Salway 2001, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Sawyer 1998, p. 74.

- ^ Millar 2010, p. 123.

- ^ Sawyer 1998, p. 69.

- ^ a b Millar 2012, p. 142.

- ^ Adams 2013, p. 31.

- ^ a b Godden 2013, p. 1.

- ^ Herman 2000, p. 17.

- ^ Baldi 2002, p. 228.

- ^ Herman 2000, p. 18–21.

- ^ Hines 1998, p. 285.

- ^ a b c Wollmann 2007, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Thomas 1981, p. 69.

- ^ Adams 2007, p. 579.

- ^ Adams 2007, pp. 579–580.

- ^ a b Jackson 1953, pp. 82–94.

- ^ Jackson 1953, p. 107.

- ^ Wollmann 2007, p. 14 (note 52).

- ^ a b Wollmann 2007, p. 17.

- ^ Adams 2007, pp. 577–623.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2000, p. 169.

- ^ a b Miller 2012, p. 27.

- ^ Miller 2012, p. 25.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2012, pp. 88.

- ^ Black 2017, pp. 11–14.

- ^ Moore 2005, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Higham & Ryan 2013, p. 70.

- ^ Higham & Ryan 2013, pp. 109–111.

- ^ Coates 2017, pp. 159–160, 168–169.

- ^ Laws 1895, pp. 303–304.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2000, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Hall 2010, pp. 55–62, 72.

- ^ a b Schrijver 2008, p. 168.

- ^ Thomas 1981, p. 65.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2012, p. 114.

- ^ Woolf 2012, pp. 371–373.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2012, p. 75.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2012, p. 89.

References[edit]

- Adams, James N. (2007). The Regional Diversification of Latin 200 BC – AD 600. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88149-4.

- Adams, J. N. (2013). Social Variation and the Latin Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-88614-7.

- Baldi, Philip (2002). The Foundations of Latin. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-017208-9.

- Black, Jeremy (2017). A History of the British Isles (4th ed.). Palgrave. ISBN 978-1-350-30675-2.

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas M. (2000). Early Christian Ireland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36395-2.

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas M. (2012). Wales and the Britons, 350-1064. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Coates, Richard (2017). "Celtic whispers: revisiting the problems of the relation between Brittonic and Old English" (PDF). Namenkundliche Informationen (Journal of Onomastics). 109/110. Leipziger Universitätsverlag: 147–173. doi:10.58938/ni576. ISBN 978-3-96023-186-8. S2CID 259010007.

- Hall, Alaric (2010). "Interlinguistic Communication In Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum". In Hall, Alaric; Timofeeva, Olga; Kiricsi, Ágnes; Fox, Bethany (eds.). Interfaces between Language and Culture in Medieval England. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18011-6.

- Herman, József (2000) [1967]. Vulgar Latin. Translated by Wright, Roger. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-02001-3.

- Higham, Nicholas; Ryan, Martin (2013). The Anglo-Saxon World. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12534-4.

- Hines, John (1998). "Archaeology and Language in a historical context: the creation of English". In Roger, Blench (ed.). Archaeology and Language II: Archaeological Data and Linguistic Hypotheses. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-11761-6.

- Jackson, Kenneth H. (1953). Gillies, William (ed.). Language and History in Early Britain: A Chronological Survey of the Brittonic Languages, First to Twelfth Century A.D. (2nd ed.). Edinburgh University Press.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic culture: A historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

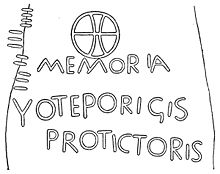

- Laws, Edward (1895). "Discovery of the Tombstone of Vortipore, Prince of Demetia". Archaeologia Cambrensis. Fifth Series. XII. London: Chas. J. Clark: 303–307.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Millar, Robert McColl (2010). Authority and Identity: A Sociolinguistic History of Europe Before the Modern Age. Palgrave. ISBN 978-1-349-31289-4.

- Millar, Robert McColl (2012). English Historical Sociolinguistics. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-4181-9.

- Miller, D. Gary (2012). External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-965426-0.

- Moore, David (2005). The Welsh wars of independence: c.410-c.1415. Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-3321-9.

- Salway, Peter (2001). A History of Roman Britain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280138-8.

- Sawyer, P. H. (1998). From Roman Britain to Norman England (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-17894-5.

- Schrijver, Peter (2008). "What Britons spoke around 400 AD". In Higham, Nick (ed.). Britons in Anglo-Saxon England. Boydell Press. p. 165-171. ISBN 978-1-84383-312-3.

- Thomas, Charles (1981). Christianity in Roman Britain to AD 500. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-520-04392-3.

- Wollmann, Alfred (2007). "Early Latin loan-words in Old English". Anglo-Saxon England. 22. Cambridge University Press: 1–26. doi:10.1017/S0263675100004282. S2CID 163041589.

- Woolf, Alex (2012). "The Britons: from Romans to Barbarians". In Goetz, Hans-Werner (ed.). Regna and Gentes: The Relationship Between Late Antique and Early Medieval Peoples and Kingdoms in the Transformation of the Roman World. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12524-7.

See also[edit]

- Anglo-Latin literature

- Anglo-Norman language

- Hermeneutic style

- Brithenig – a constructed language imagining if British Latin had displaced Celtic languages

- Roman Inscriptions of Britain

Further reading[edit]

- Ashdowne, Richard K.; White, Carolinne, eds. (2017). Latin in Medieval Britain. Proceedings of the British Academy. Vol. 206. London: Oxford University Press/British Academy. ISBN 978-0-19-726608-3.

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas (1995). "Language and Society among the Insular Celts, AD 400–1000". In Green, Miranda J. (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge Worlds Series. London: Psychology Press. pp. 703–736. ISBN 978-0-415-14627-2.

- Godden, Malcolm, ed. (2013). The Cambridge Companion to Old English Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19332-0.

- Gratwick, A. S. (1982). "Latinitas Britannica: Was British Latin Archaic?". In Brooks, Nicholas (ed.). Latin and the Vernacular Languages in Early Medieval Britain. Studies in the Early History of Britain. Leicester: Leicester University Press. pp. 1–79. ISBN 978-0-7185-1209-5.

- Howlett, D. R.; et al., eds. (2012). Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. (published in 17 volumes between 1975 and 2013)

- MacManus, Damian (1987). "Linguarum Diversitas: Latin and the Vernaculars in Early Medieval Britain". Peritia. 3: 151–188. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.62. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Mann, J. C. (1971). "Spoken Latin in Britain as Evidenced by the Inscriptions". Britannia. 2. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies: 218–224. doi:10.2307/525811. JSTOR 525811. S2CID 163766377.

- Schrijver, Peter (2002). "The Rise and Fall of British Latin". In Filppula, Markku; Klemola, Juhani; Pitkänen, Heli (eds.). The Celtic Roots of English. Studies in Languages. Vol. 37. Joensuu: University of Joensuu. pp. 87–110. ISSN 1456-5528.

- Shiel, Norman (1975). "The Coinage of Carausius as a Source of Vulgar Latin". Britannia. 6. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies: 146–149. doi:10.2307/525996. JSTOR 525996. S2CID 162699214.

- Smith, Colin (1983). "Vulgar Latin in Roman Britain: Epigraphic and other Evidence". Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt. II. 29 (2): 893–948.

- Snyder, Christopher A. (1996). Sub-Roman Britain (AD 400–600): A Gazetteer of Sites. British Archaeological Reports British Series. Vol. 247. Oxford: Tempus Reparatum. ISBN 978-0-86054-824-9.