| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Activase, Actilyse, Cathflo Activase, others |

| Other names | t-PA, rt-PA |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C2569H3928N746O781S40 |

| Molar mass | 59042.52 g·mol−1 |

| (verify) | |

Alteplase, sold under the brand name Activase among others, is a biosynthetic form of human tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA). It is a thrombolytic medication used to treat acute ischemic stroke, acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (a type of heart attack), pulmonary embolism associated with low blood pressure, and blocked central venous catheter.[5] It is given by injection into a vein or artery.[5] Alteplase is the same as the normal human plasminogen activator produced in vascular endothelial cells[6] and is synthesized via recombinant DNA technology in Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO). Alteplase causes the breakdown of a clot by inducing fibrinolysis.[7]

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[8]

Medical uses[edit]

Alteplase is indicated for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke, acute myocardial infarction, acute massive pulmonary embolism, and blocked catheters.[5][2][3] Similar to other thrombolytic drugs, alteplase is used to dissolve clots to restore tissue perfusion, but this can vary depending on the pathology.[9][10] Generally, alteplase is delivered intravenously into the body.[7] To treat blocked catheters, alteplase is administered directly into the catheter.[7]

Ischemic stroke[edit]

In adults diagnosed with acute ischemic stroke, thrombolytic treatment with alteplase is the standard of care.[10][11] Administration of alteplase is associated with improved functional outcomes and reduced incidence of disability.[12] Alteplase used in conjunction with mechanical thrombectomy is associated with better outcomes.[13][14]

Pulmonary embolism[edit]

As of 2019, alteplase is the most commonly used medication to treat pulmonary embolism (PE).[15] Alteplase has a short infusion time of 2 hours and a half-life of 4–6 minutes.[15] Alteplase has been approved by the FDA, and treatment can be done via systemic thrombolysis or catheter-directed thrombolysis.[15][16]

Systemic thrombolysis can quickly restore right ventricular function, heart rate, and blood pressure in patients with acute PE.[17] However, standard doses of alteplase used in systemic thrombolysis may lead to massive bleeding, such as intracranial hemorrhage, particularly in older patients.[15] A systematic review has shown that low-dose alteplase is safer than and as effective as the standard amount.[18]

Blocked catheters[edit]

Alteplase can be used in small doses to clear blood clots that obstruct a catheter, reopening the catheter so it can continue to be used.[3][12] Catheter obstruction is commonly observed with a central venous catheter.[19] Currently, the standard treatment for catheter obstructions in the United States is alteplase administration.[6] Alteplase is effective and low risk for treating blocked catheters in adults and children.[6][19] Overall, adverse effects of alteplase for clearing blood clots are rare.[20] Novel alternatives to treat catheter occlusion, such as tenecteplase, reteplase, and recombinant urokinase, offer the advantage of shorter dwell times than alteplase.[19]

Contraindications[edit]

A person should not receive alteplase treatment if testing shows they are not suffering from an acute ischemic stroke or if the risks of treatment outweigh the likely benefits.[10] Alteplase is contraindicated in those with bleeding disorders that increase a person's tendency to bleed and in those with an abnormally low platelet count.[14] Active internal bleeding and high blood pressure are additional contraindications for alteplase.[14] The safety of alteplase in the pediatric population has not been determined definitively.[14] Additional contraindications for alteplase when used specifically for acute ischemic stroke include current intracranial hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage.[21] Contraindications for use of alteplase in people with a STEMI are similar to those of acute ischemic stroke.[9] People with an acute ischemic stroke may also receive other therapies including mechanical thrombectomy.[10]

Adverse effects[edit]

Given that alteplase is a thrombolytic medication, a common adverse effect is bleeding, which can be life-threatening.[22] Adverse effects of alteplase include symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage and fatal intracranial hemorrhage.[22]

Angioedema is another adverse effect of alteplase, which can be life-threatening if the airway becomes obstructed.[2] Other side effects may rarely include allergic reactions.[5]

Mechanism of action[edit]

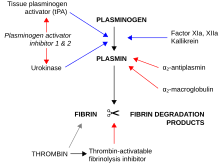

Alteplase binds to fibrin in a blood clot and activates the clot-bound plasminogen.[7] Alteplase cleaves plasminogen at the site of its Arg561-Val562 peptide bond to form plasmin.[7] Plasmin is a fibrinolytic enzyme that cleaves the cross-links between polymerized fibrin molecules, causing the blood clot to break down and dissolve, a process called fibrinolysis.[7]

Regulation and inhibition[edit]

Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 stops alteplase activity by binding to it and forming an inactive complex, which is removed from the bloodstream by the liver.[7] Fibrinolysis by plasmin is extremely short-lived due to plasmin inhibitors, which inactivate and regulate plasmin activity.[7]

History[edit]

In 1995, a study by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke showed the effectiveness of administering intravenous alteplase to treat ischemic stroke.[23] This sparked a medical paradigm shift as it redesigned stroke treatment in the emergency department to allow for timely assessment and therapy for ischemic stroke patients.[23]

Society and culture[edit]

Alteplase was added to the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines in 2019, for use in ischemic stroke.[24][25]

Legal status[edit]

In May 1987, the United States FDA requested additional data for the drug rather than approve it outright, causing Genentech stock prices to fall by nearly one quarter. The decision was described as a surprise to the company as well as many cardiologists and regulators,[26] and it generated significant criticism of the FDA, including from The Wall Street Journal editorial board.[27][28]

After results from two additional trials were obtained,[27] Alteplase was approved for medical use in the United States in November 1987 for the treatment of myocardial infarction.[5][2][29][30] This was just seven years after the first efforts were made to produce recombinant t-PA, making it one of the fastest drug developments in history.[30]

Economics[edit]

The cost of alteplase in the United States increased by 111% between 2005 and 2014, despite there being no proportional increase in the costs of other prescription drugs.[31] However, alteplase continues to be cost-effective.[31]

Brand names[edit]

Alteplase is marketed as Actilyse, Activase, and Cathflo or Cathflo Activase.[2][3][32][33]

Controversies[edit]

Alteplase is extremely underused in low- and middle-income countries.[34] This may be due to its high cost and the fact that it is often not covered by health insurance.[34]

There may be citation bias in the literature on alteplase in ischemic stroke, as studies reporting positive results for tissue plasminogen activator are more likely to be cited in following studies than those reporting negative or neutral results.[35]

There is a sex difference in the use of intravenous tissue plasminogen activator, as it is less likely to be used for women with acute ischemic stroke than men.[36] However, this difference has been improving since 2008.[36]

References[edit]

- ^ Australian Public Assessment Report for Alteplase (AusPAR) (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) (Report). February 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Activase- alteplase kit". DailyMed. 5 December 2018. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Cathflo Activase- alteplase injection, powder, lyophilized, for solution". DailyMed. 6 September 2019. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ "Actilyse". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Alteplase Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ a b c Baskin JL, Pui CH, Reiss U, Wilimas JA, Metzger ML, Ribeiro RC, et al. (July 2009). "Management of occlusion and thrombosis associated with long-term indwelling central venous catheters". Lancet. 374 (9684): 159–69. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60220-8. PMC 2814365. PMID 19595350.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jilani TN, Siddiqui AH (April 2020). "Tissue Plasminogen Activator". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29939694. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ a b O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, et al. (January 2013). "2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Circulation. 127 (4): e362-425. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6. PMID 23247304.

- ^ a b c d Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, et al. (December 2019). "Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association". Stroke. 50 (12): e344–e418. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000211. PMID 31662037.

- ^ Powers WJ (July 2020). Solomon CG (ed.). "Acute Ischemic Stroke". The New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (3): 252–260. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1917030. PMID 32668115. S2CID 220584673.

- ^ a b Reed M, Kerndt CC, Nicolas D (2020). "Alteplase". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29763152. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ Mistry EA, Mistry AM, Nakawah MO, Chitale RV, James RF, Volpi JJ, et al. (September 2017). "Mechanical Thrombectomy Outcomes With and Without Intravenous Thrombolysis in Stroke Patients: A Meta-Analysis". Stroke. 48 (9): 2450–2456. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017320. PMID 28747462. S2CID 3751956.

- ^ a b c d Demaerschalk BM, Kleindorfer DO, Adeoye OM, Demchuk AM, Fugate JE, Grotta JC, et al. (February 2016). "Scientific Rationale for the Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Intravenous Alteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association". Stroke. 47 (2): 581–641. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000086. PMID 26696642. S2CID 9381101.

- ^ a b c d Ucar EY (June 2019). "Update on Thrombolytic Therapy in Acute Pulmonary Thromboembolism". The Eurasian Journal of Medicine. 51 (2): 186–190. doi:10.5152/eurasianjmed.2019.19291. PMC 6592452. PMID 31258361.

- ^ Martin C, Sobolewski K, Bridgeman P, Boutsikaris D (December 2016). "Systemic Thrombolysis for Pulmonary Embolism: A Review". P & T. 41 (12): 770–775. PMC 5132419. PMID 27990080.

- ^ Engelberger RP, Kucher N (March 2014). "Ultrasound-assisted thrombolysis for acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review". European Heart Journal. 35 (12): 758–64. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu029. PMID 24497337.

- ^ Zhang Z, Zhai ZG, Liang LR, Liu FF, Yang YH, Wang C (March 2014). "Lower dosage of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA) in the treatment of acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Thrombosis Research. 133 (3): 357–63. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2013.12.026. PMID 24412030.

- ^ a b c Baskin JL, Reiss U, Wilimas JA, Metzger ML, Ribeiro RC, Pui CH, et al. (May 2012). "Thrombolytic therapy for central venous catheter occlusion". Haematologica. 97 (5): 641–50. doi:10.3324/haematol.2011.050492. PMC 3342964. PMID 22180420.

- ^ Hilleman D, Campbell J (October 2011). "Efficacy, safety, and cost of thrombolytic agents for the management of dysfunctional hemodialysis catheters: a systematic review". Pharmacotherapy. 31 (10): 1031–40. doi:10.1592/phco.31.10.1031. PMID 21950645. S2CID 2092899.

- ^ Parker S, Ali Y (October 2015). "Changing contraindications for t-PA in acute stroke: review of 20 years since NINDS". Current Cardiology Reports. 17 (10): 81. doi:10.1007/s11886-015-0633-5. PMID 26277361. S2CID 26427160.

- ^ a b Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P, Blackwell L, Albers G, Bluhmki E, et al. (November 2014). "Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials". Lancet. 384 (9958): 1929–35. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60584-5. PMC 4441266. PMID 25106063.

- ^ a b Campbell BC, Meretoja A, Donnan GA, Davis SM (August 2015). "Twenty-Year History of the Evolution of Stroke Thrombolysis With Intravenous Alteplase to Reduce Long-Term Disability". Stroke. 46 (8): 2341–6. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007564. PMID 26152294. S2CID 207614164.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). Executive summary: the selection and use of essential medicines 2019: report of the 22nd WHO Expert Committee on the selection and use of essential medicines. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325773. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.05. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Sun M (3 July 1987). "FDA Puts New Heart Drug on Hold: A surprise decision by the FDA to withhold approval of TPA, a potent clot-dissolving drug, highlights a scientific debate among cardiologists". Science. 237 (4810): 16–18. doi:10.1126/science.3110948. PMID 3110948.

- ^ a b Carpenter DP (2010). Reputation and power : organizational image and pharmaceutical regulation at the FDA. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 2–7. ISBN 9780691141794.

- ^ Sun M (28 July 1987). "Heart Drug in Limbo". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "Activase: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ a b Collen D, Lijnen HR (August 2009). "The tissue-type plasminogen activator story". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 29 (8): 1151–5. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179655. PMID 19605778.

- ^ a b Kleindorfer D, Broderick J, Demaerschalk B, Saver J (July 2017). "Cost of Alteplase Has More Than Doubled Over the Past Decade". Stroke. 48 (7): 2000–2002. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.116.015822. PMID 28536176. S2CID 3729672.

- ^ "Cathflo Activase Uses, Side Effects & Warnings". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Collen D, Lijnen HR (April 2004). "Tissue-type plasminogen activator: a historical perspective and personal account". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2 (4): 541–6. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7933.2004.00645.x. PMID 15102005. S2CID 42654928.

- ^ a b Khatib R, Arevalo YA, Berendsen MA, Prabhakaran S, Huffman MD (2018). "Presentation, Evaluation, Management, and Outcomes of Acute Stroke in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Neuroepidemiology. 51 (1–2): 104–112. doi:10.1159/000491442. PMC 6322558. PMID 30025394.

- ^ Misemer BS, Platts-Mills TF, Jones CW (September 2016). "Citation bias favoring positive clinical trials of thrombolytics for acute ischemic stroke: a cross-sectional analysis". Trials. 17 (1): 473. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1595-7. PMC 5039798. PMID 27677444. S2CID 9343300.

- ^ a b Strong B, Lisabeth LD, Reeves M (July 2020). "Sex differences in IV thrombolysis treatment for acute ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Neurology. 95 (1): e11–e22. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000009733. PMID 32522796. S2CID 219586256.