| |

| Date | February 20, 2003 |

|---|---|

| Time | 11:07 p.m. (EST) |

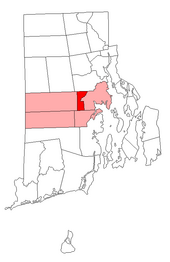

| Location | West Warwick, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 41°41′03.6″N 71°30′39.2″W / 41.684333°N 71.510889°W |

| Cause | Ignition of acoustic foam by pyrotechnics. Fireworks accident. |

| Deaths | 100[a] |

| Non-fatal injuries | 230 |

The Station nightclub fire occurred on the evening of February 20, 2003, at The Station, a nightclub and hard rock music venue in West Warwick, Rhode Island, United States, killing 100 people and injuring 230. During a concert by the rock band Great White, a pyrotechnic display ignited flammable acoustic foam in the walls and ceilings surrounding the stage. Within six minutes, the entire building was engulfed in flames. The fire was the deadliest fireworks accident in U.S. history and the fourth-deadliest nightclub fire in U.S. history. It was also the second-deadliest nightclub fire in New England, behind the 1942 Cocoanut Grove fire.

After the fire, multiple civil and criminal cases were filed. Daniel Biechele, the tour manager for Great White who had ignited the pyrotechnics, pled guilty to 100 counts of involuntary manslaughter in 2006 and was sentenced to fifteen years in prison with four to serve. Biechele was released from prison in 2008 after some families of the victims expressed their support for his parole. Jeffrey and Michael Derderian, the owners of the Station, pleaded no contest and avoided a trial: Michael received the same sentence as Biechele and was released from prison in 2009, while Jeffrey received a sentence of 500 hours of community service. Legal action against several parties, including Great White, were resolved with monetary settlements by 2008.

Station Fire Memorial Park, a permanent memorial to the victims of the fire, was opened in May 2017 at the site where the Station once stood.

Background[edit]

The Station[edit]

The Station was a nightclub that was located on the corner of Cowesett Avenue and Kulas Road in West Warwick, Rhode Island.[1] The building that would become The Station was built in 1946 and was originally used as a gin mill.[2]

Prior to being converted into a nightclub and concert venue, the Station building had been used as a restaurant and tavern.[3] A fire had previously occurred at the building in 1972 while it was used as a restaurant called Julio's.[4] No occupants were in the building during the 1972 fire, but the interior was significantly damaged.[4] Another restaurant opened in the building in 1974.[4] In 1985, it was converted to a pub, which closed sometime in the late 1980s, and a nightclub was opened in its place in 1991.[4] The nightclub was purchased by brothers Michael and Jeffrey Derderian in March 2000.[2]

In the months prior to the fire, the building had been inspected twice by West Warwick fire marshal Denis Larocque.[2] The club was cited for nine minor code violations during the first inspection in November 2002, but was not cited for the flammable polyurethane foam the venue used for soundproofing, which was against code.[2] The follow-up inspection in December 2002 also did not cite the foam, and the inspector gave the building an "All OK" rating on his inspection form.[2] Larocque later told the Rhode Island State Police that he had not spotted the polyurethane foam during the November 2002 inspection because he was upset after finding an illegal inward swinging door that he had previously asked to be removed from the building.[2]

Prior to the fire, the Station often hosted concerts by 1980s hard rock groups and tribute bands.[5] Local bands that had played at the Station prior to the fire had used pyrotechnics during their concerts without incident, including a Kiss tribute band that had set off fireballs during their show in August 2002.[6]

Great White[edit]

Great White, the headlining band of the February 20 concert, had risen to fame as part of the glam metal scene of the late 1980s and early 1990s.[7][8] They were best known for their 1989 cover of Ian Hunter's "Once Bitten, Twice Shy", which reached the top ten of the Billboard Hot 100.[9][10][8] At the time of their performance at the Station, Great White had two of its original members in its lineup: Lead singer Jack Russell and guitarist Mark Kendall.[11] For the 2003 tour, the band was billed as "Jack Russell's Great White".[12] Kendall, who had co-founded the band with Russell in 1977, had rejoined Russell's version of the group in 2002.[12] The rest of the lineup included guitarist Ty Longley, who died in the fire, bass guitarist David Filice, and drummer Eric Powers.[12] Great White's popularity had waned in the decade prior to the Station fire, and they had been performing on a touring circuit of small clubs with capacities of up to 500 people.[11] Although the band was officially known as Jack Russell's Great White at the time, and their tour was initially named after Russell's 2002 solo album For You, they were billed by the Station as simply Great White.[13]

In February 2003, Great White was on an eighteen date concert tour, and they had been using a pyrotechnic display during their performances that some club owners had denied them permission to use, citing safety concerns.[11] Dominic Santana, the owner of The Stone Pony in Asbury Park, New Jersey, told reporters that Great White had used pyrotechnics during their February 14, 2003 performance at the venue without his permission, and their contract and rider did not mention pyrotechnics displays.[14] In the aftermath of the fire, Great White and the owners of the Station disputed whether the band were allowed to use the pyrotechnic display during their concert.[8]

Great White had two opening acts for the February 20 concert: Trip, a group from Vancouver, Washington, and Fathead, a local Rhode Island band.[15][16] All the members of Trip escaped the Station without injury, but two members of Fathead, cousins Keith and Steven Mancini, along with Steven’s wife Andrea, died in the fire.[16][17]

The concert was emceed by Michael Gonsalves, a disc jockey for Providence rock radio station WHJY who was also known as "Doctor Metal".[18][19] Gonsalves was the host of the WHJY program The Metal Zone, at the time the longest-running heavy metal radio program in the United States.[20]

Fire[edit]

Ignition[edit]

Great White started their performance at 11:07 p.m. on February 20.[21] A total of 462 people were in attendance, even though the club's maximum licensed capacity was cited as 404.[2]

The fire started shortly after Great White began performing their opening number, "Desert Moon".[22] During the performance, pyrotechnics set off by tour manager Daniel Biechele ignited the flammable acoustic foam on both sides and the top center of the drummer's alcove at the back of the stage. The pyrotechnics were gerbs, cylindrical devices that produce a controlled spray of sparks.[22] Biechele used four gerbs that were set to spray sparks 15 feet (4.6 m) for fifteen seconds.[9] Two gerbs were at 45-degree angles, with the middle two pointing straight up. The flanking gerbs became the principal cause of the fire.

Sparks from the gerbs ignited the insulation foam, and flames were visible on the wall above the stage within nine seconds of their ignition.[21] The flames were initially thought to be part of the act; only as the fire reached the ceiling and smoke began to bank down did people realize it was uncontrolled.[21] Twenty seconds after the pyrotechnics ended, the band stopped playing and lead singer Jack Russell calmly remarked into the microphone, "Wow... that's not good."[23] Within 40 seconds of the ignition, Great White had stopped playing and left the stage and the venue's fire alarm began to sound, but it was not connected to the local fire department.[21] The Station did not have a sprinkler system installed.[21] Thick smoke began to fill the Station one minute after the ignition and the crowd began to escape the building.[21] The fire spread throughout the building, which was completely engulfed within six minutes of the pyrotechnic ignition.[21]

Response[edit]

By this time, the nightclub's fire alarm had activated, and although there were four possible exits, most people headed for the front door through which they had entered.[9] The ensuing crowd crush in the narrow hallway led to that exit being blocked completely and resulted in numerous deaths and injuries among the patrons and staff.[9] Multiple survivors claimed that two bouncers blocked the stage door as attendees attempted to escape the building, stating the door was only to be used by the band.[24][25]

The fire was reported to the West Warwick Fire Department by cellular phone calls to 911 within sixty seconds of ignition.[26] A West Warwick police officer who was already at the scene also reported the fire to police dispatch.[26] The first West Warwick fire engine arrived at the scene at 11:13 p.m., followed by three other trucks shortly thereafter.[26] Hundreds of firefighters responded to the fire, including every available West Warwick firefighter.[27] Fire departments in Warwick, Coventry, and Cranston rendered mutual aid to the fire site.[28] The Cowesett Inn restaurant across the street from the Station acted as an ad-hoc burn triage and command center for first responders.[29] A portion of the nightclub roof collapsed at 11:57 p.m., and a second portion in the building's sunroom collapsed at 12:07 a.m..[26] Individuals who needed medical treatment were transported to Kent Hospital, which was filled to maximum capacity due to the fire.[30] By 1:30 a.m. on February 21, all the affected individuals had been transported and the street had been cleared.[30]

Aftermath and casualties[edit]

Of the 462 people in the building for the concert, 100 were killed, 230 were injured, and 132 escaped uninjured.[31] Ninety-six individuals died at the scene, and four more died in the hospital in the following weeks.[21] Among those who died in the fire were Great White guitarist Ty Longley, and the show's emcee, WHJY DJ Mike "Dr Metal" Gonsalves.[32]

Four employees of the Station were killed in the fire.[33] In April 2003, the Derderians were fined $1.07 million for failing to carry workers' compensation insurance for their employees.[33] The fine was not resolved until 2013, ten years after the fire, when it was upheld by a judge.[34]

Providence Phoenix columnist Ian Donnis wrote of the effect that the fire had on the close-knit Rhode Island community, "The loss of so much life would represent a tragedy anywhere, but it struck especially hard in Rhode Island, the nation's smallest state, where no place is more than an hour away by car..."[5] Many of the survivors of the fire developed post-traumatic stress disorder after the event.[35]

Recording and account[edit]

The fire, from its inception, was caught on videotape by cameraman Brian Butler for WPRI-TV of Providence, and the beginning of that tape was released to national news stations.[36] Butler was there for a planned piece on nightclub safety being reported by Jeffrey A. Derderian, a WPRI news reporter who was also a part-owner of The Station.[37] The report had been inspired by the E2 nightclub stampede in Chicago that killed 21 people three days earlier.[38] Derderian had begun working for WPRI on February 17, three days before the fire.[39] WPRI-TV and Derderian were criticized for the conflict of interest in having a reporter do a report concerning his own property.[40][37] Derderian resigned from WPRI on June 30.[39]

At the scene of the fire, Butler gave this account of the tragedy:[41]

It was that fast. As soon as the pyrotechnics stopped, the flame had started on the egg crate backing behind the stage, and it just went up the ceiling. And people stood and watched it, and some people backed off. When I turned around, some people were already trying to leave, and others were just sitting there going, "Yes, that's great!" And I remember that statement, because I was, like, this is not great. This is the time to leave.

At first, there was no panic. Everybody just kind of turned. Most people still just stood there. In the other rooms, the smoke hadn't gotten to them, the flame wasn't that bad, they didn't think anything of it. Well, I guess once we all started to turn toward the door, and we got bottlenecked into the front door, people just kept pushing, and eventually everyone popped out of the door, including myself.

That's when I turned back. I went around back. There was no one coming out the back door anymore. I kicked out a side window to try to get people out of there. One guy did crawl out. I went back around the front again, and that's when you saw people stacked on top of each other, trying to get out of the front door. And by then, the black smoke was pouring out over their heads.

I noticed when the pyro stopped, the flame had kept going on both sides. And then on one side, I noticed it come over the top, and that's when I said, 'I have to leave.' And I turned around, I said, 'Get out, get out, get to the door, get to the door!' And people just stood there.

There was a table in the way at the door, and I pulled that out just to get it out of the way so people could get out easier. And I never expected it take off as fast as it did. It just -- it was so fast. It had to be two minutes tops before the whole place was black smoke.

Investigation[edit]

NIST report[edit]

A National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) investigation of the fire under the authority of the National Construction Safety Team Act, using computer simulations with FDS and a mockup of the stage area and dance floor, concluded that a fire sprinkler system would have contained the fire long enough to give everyone time to exit safely.[42][43] The Station, which was built in 1946, was exempt from a sprinkler requirement in the state fire code through a grandfather clause, which stated that buildings constructed before 1976 were not required to have a sprinkler system.[44] The NIST report was released on March 3, 2005 and was made available in two parts on June 30, 2005.[43][45]

Grand jury investigation[edit]

An investigation of the fire by a Rhode Island state grand jury was started by then-Rhode Island Attorney General Patrick Lynch on February 26, 2003.[2][46] On December 9, 2003, the grand jury announced indictments against Station owners Jeffrey and Michael Derderian and Great White road manager Daniel M. Biechele.[2] The three were each charged with 100 counts of involuntary manslaughter with criminal negligence and 100 counts of involuntary manslaughter in violation of a misdemeanor.[47] West Warwick fire marshal Denis Larocque was not charged by the grand jury, as Lynch had cited a state law that prevented charges against fire marshals without proof of bad faith.[48] The grand jury also did not return charges against the band's lead singer Jack Russell.[49][50]

Lynch told 48 Hours that his investigation found that the fire spread quickly due to the foam the Derderians had installed in the Station's walls and ceilings as a response to noise complaints.[9] The lack of usable exits was also a factor, as was the inward door that Larocque had found and asked to be removed.[9] Jeffrey Derderian said the door was also installed due to noise, and they had removed it as asked, but sometimes re-installed it if the venue was going to be loud that night, and it was used by the band to escape the building during the fire.[9] Michael Derderian told 48 Hours that it was "Undisputable" that the building's use of flammable packing foam instead of flame retardant sound foam was the cause of the fire's spread, but the brothers claimed that they had ordered sound foam and had received the packing foam instead.[9]

Other causes[edit]

The foam was sold to the Derderians by American Foam.[9] In 2005, the Rhode Island Attorney General office received a fax from Barry Warner, a former employee of American Foam who lived nearby the Station, who claimed the company had known about the dangers of polyurethane foam but did not warn their employees about it.[9] Although Warner was called to testify to a grand jury, he was not asked about the fax.[9] American Foam refuted the claims in Warner's fax.[9] In 2008, American Foam agreed to pay $6.3 million to the families of the victims of the fire.[51]

Victims' families have also cited overcrowding in the venue as a cause for the casualties during the fire.[48] Larocque had set various capacities for the Station in the years prior to the fire based on whether pool tables and other items could be moved.[48] The capacity for the Station was either 258 or 404, depending on how the building was being used.[2] The final tally by The Providence Journal of people inside the Station during the fire totaled 462.[2]

Criminal trials[edit]

Daniel Biechele[edit]

The first criminal trial was against Great White's tour manager, Daniel Michael Biechele, 26, from Orlando, Florida. This trial was scheduled to start May 1, 2006, but Biechele, against his lawyers' advice,[52] pleaded guilty to 100 counts of involuntary manslaughter on February 7, 2006, in what he said was an effort to "bring peace, I want this to be over with."[52]

Sentencing and statement[edit]

On May 10, 2006, State Prosecutor Randall White asked that Biechele be sentenced to ten years in prison, the maximum allowed under the plea bargain, citing the massive loss of life in the fire and the need to send a message.[52] Speaking to the public for the first time since the fire, Biechele stated:

For three years, I've wanted to be able to speak to the people that were affected by this tragedy, but I know that there's nothing that I can say or do that will undo what happened that night.

Since the fire, I have wanted to tell the victims and their families how truly sorry I am for what happened that night and the part that I had in it. I never wanted anyone to be hurt in any way. I never imagined that anyone ever would be.

I know how this tragedy has devastated me, but I can only begin to understand what the people who lost loved ones have endured. I don't know that I'll ever forgive myself for what happened that night, so I can't expect anybody else to.

I can only pray that they understand that I would do anything to undo what happened that night and give them back their loved ones.

I'm so sorry for what I have done, and I don't want to cause anyone any more pain.

I will never forget that night, and I will never forget the people that were hurt by it.

I am so sorry.[53]

Superior Court Judge Francis J. Darigan Jr. sentenced Biechele to fifteen years in prison, with four to serve and eleven years suspended, plus three years' probation, for his role in the fire.[54] Darigan remarked, "The greatest sentence that can be imposed on you has been imposed on you by yourself."[55] Biechele was released in March 2008.[56]

The sentence drew mixed reactions in the courtroom. Many of the families believed that the punishment was just; others had hoped for a more severe sentence.[57]

Support for parole and aftermath[edit]

On September 4, 2007, some families of the fire's victims expressed their support for Biechele's parole.[58] Leland Hoisington, whose 28-year-old daughter, Abbie, was killed in the fire, told reporters, "I think they should not even bother with a hearing—just let Biechele out ... I just don't find him as guilty of anything."[58] The state parole board received approximately twenty letters, the majority of which expressed their sympathy and support for Biechele, some going as far as to describe him as a "scapegoat" with limited responsibility. Parole board chairwoman Lisa Holley told journalists of her surprise at the forgiving attitude of the families, saying, "I think the most overwhelming part of it for me was the depth of forgiveness of many of these families that have sustained such a loss."[58]

Dave Kane and Joanne O'Neill, parents of youngest victim Nicholas O'Neill, released their letter to the board to reporters. "In the period following this tragedy, it was Mr. Biechele, alone, who stood up and admitted responsibility for his part in this horrible event ... He apologized to the families of the victims and made no attempt to mitigate his guilt," the letter said.[58] Others pointed out that Biechele had sent handwritten letters to the families of each of the 100 victims and that he had a work release position in a local charity.[58]

On September 19, 2007, the Rhode Island Parole Board announced that Biechele would be released in March 2008. Biechele was released from prison on March 19, 2008.[59]

Biechele's parole and probation expired in March 2011.[60] As of 2013[update], Biechele lived in Florida with his wife and two children.[60]

Michael and Jeffrey Derderian[edit]

Following Biechele's trial, The Station's owners, Michael and Jeffrey Derderian, were scheduled to receive separate trials. However, on September 21, 2006, Judge Darigan announced that the brothers had changed their pleas from "not guilty" to "no contest", thereby avoiding a trial.[61] Michael Derderian received fifteen years in prison, with four to serve and eleven years suspended, plus three years' probation—the same sentence as Biechele. Jeffrey Derderian received 500 hours of community service.[62]

In a letter to the victims' families, Judge Darigan wrote that he accepted the deal because he wanted to avoid "Public exposition of the tragic, explicit and horrific events experienced by the victims of this fire, both living and dead."[63] He added that the difference in the brothers' sentences reflected their respective involvement with the purchase and installation of the flammable foam.[63] Rhode Island Attorney General Patrick C. Lynch objected strenuously to the plea bargain, saying that both brothers should have received jail time and that Michael Derderian should have received more time than Biechele.[61]

In January 2008, the Parole Board decided to grant Michael Derderian an early release; he was scheduled to be released from prison in September 2009, but was granted his release in June 2009 for good behavior.[64]

Civil settlements[edit]

As of September 2008, at least $115 million in settlement agreements had been paid, or offered, to the victims or their families by various defendants:

- In September 2008, The Jack Russell Tour Group Inc. offered $1 million in a settlement to survivors and victims' relatives,[65] the maximum allowed under the band's insurance plan.[66]

- Club owners Jeffrey and Michael Derderian reached a settlement of $813,000 with survivors and victims' families in September 2008.[67]

- The State of Rhode Island and the town of West Warwick agreed to pay $10 million as settlement.[68]

- Sealed Air Corporation agreed to pay $25 million as settlement. Victims' lawyers said that Sealed Air made polyethylene foam that had been installed at the Station in 1996, which produced toxic gas when it burned during the fire.[69]

- In February 2008, Providence television station WPRI-TV and their then-owners LIN TV made an out-of-court settlement of $30 million as a result of the claim that their video journalist Brian Butler was said to be obstructing escape and not sufficiently helping people exit.[70]

- In March 2008, JBL Speakers settled out of court for $815,000. JBL was accused of using flammable foam inside their speakers. The company denied any wrongdoing.[71]

- Anheuser-Busch has offered $5 million.[72] McLaughlin & Moran, Anheuser-Busch's distributor, has offered $16 million.[72]

- Home Depot and Polar Industries, Inc. (a Connecticut-based insulation company) made a settlement offer of $5 million.[73]

- Providence radio station WHJY-FM promoted the show, which was emcee'd by its DJ, Mike "The Doctor" Gonsalves (who was one of the casualties that night). Clear Channel Broadcasting, WHJY's parent company, paid a settlement of $22 million in February 2008.[74]

- American Foam Corporation, who sold the insulation to The Station nightclub, agreed in 2008 to pay $6.3 million to settle lawsuits relating to the fire.[75]

In 2021, 48 Hours described the total civil payments to the victims and families as $176 million.[9]

Memorials and benefits[edit]

Thousands of mourners attended an interfaith memorial service at St. Gregory the Great Church in Warwick on February 24, 2003, to remember those lost in the fire.[76] Another memorial was later that night the West Warwick Civic Center.[77]

A benefit memorial concert was held in February 2008 at the Dunkin' Donuts Center in Providence and featured performances by Tesla, Twisted Sister, Winger, Gretchen Wilson, and John Rich.[78] The event raised at least $25,000 in donations for the Station Family Fund, and was broadcast in March by VH1 and VH1 Classic.[78]

On the twentieth anniversary of the fire on February 20, 2023, Rhode Island governor Dan McKee ordered flags in Rhode Island lowered to half-staff for the day and the Rhode Island State House to be illuminated in memory of the 100 victims.[79]

Station Fire Memorial Park[edit]

The site of the fire was cleared, and a multitude of crosses were placed as memorials, left by loved ones of the deceased. On May 20, 2003, nondenominational services began to be held at the site of the fire for a number of months. Access remains open to the public, and memorial services are held each February 20.[80]

A permanent memorial at the site of the fire has been erected and named the Station Fire Memorial Park.[81] In August 2016, the site was reported to have been being used as a PokeStop in Pokémon Go, to uproar from victims' families.[82] The stop was removed from the game by developer Niantic later that month.[83]

In June 2003, the Station Fire Memorial Foundation (SFMF) was formed with the purpose of purchasing the property, to build and maintain a memorial.[84] In September 2012, the owner of the land, Ray Villanova, donated the site to the SFMF.[85] By April 2016, $1.65 million of the $2 million fundraising goal had been achieved and construction of the Station Fire Memorial Park had commenced.[86][87] The memorial dedication ceremony took place on May 21, 2017.[88]

Aftermath[edit]

Great White, Jack Russell, and Mark Kendall[edit]

Russell considered disbanding Great White after the fire, but reconsidered when he decided to embark on a benefit tour.[49] The tour started five months after the fire, and each concert began with a prayer for survivors and families.[89] The band raised $185,000 for the Station Family Fund during the tour.[90] The band initially retired "Desert Moon", the song they were performing when the fire began, from their concert set list.[89] "I don't think I could ever sing that song again," said Russell.[89] Kendall said in 2005, "We haven't played that song. Things that bring back memories of that night we try to stay away from. And that song reminds us of that night. We haven't played it since then and probably never will."[91]

Two years to the day after the fire, band members Russell and Kendall, along with Great White's attorney, Ed McPherson, appeared on CNN's Larry King Live with three survivors of the fire and the father of Longley, to discuss how their lives had changed since the incident.[92]

Russell left Great White in 2010.[93] In the years following the fire, Great White split into two separate groups, one led by Russell and the other by Kendall.[94] Kendall's version of the band holds the copyright for the Great White name.[95] When Russell launched his version of the band in 2012, Kendall's group responded that Russell had no right to use the name.[93] After a 2013 legal settlement between the two parties, Kendall's band retained the Great White name, while Russell's band was allowed to use the name Jack Russell's Great White.[96] By 2013, Russell's group had resumed playing "Desert Moon".[95]

Russell performed a benefit show in February 2013 in Hermosa Beach, California, in commemoration of the tenth anniversary of the fire.[90] Russell planned to donate the proceeds to the Station Fire Memorial Foundation, but the organization asked to be disassociated from the concert, citing the animosity still felt by many of the survivors and surviving families.[97] Russell raised about $180 from the concert, but the Memorial Foundation refused the donation, a decision supported by Kendall.[49] In 2013, Kendall told The Providence Journal that he maintained amicable contact with some survivors, victims' families, and the Station Fire Memorial Foundation.[12] Russell's relation with some survivors and families has been strained, although he remains close to Longley's family.[95][49]

Neither version of Great White performed in any of the six New England states for over a decade following the fire.[94] Russell's group made its first New England appearance in twelve years at a harvest festival in Mechanic Falls, Maine, in August 2015.[94] Kendall's version of Great White was to perform at the Mohegan Sun casino in Uncasville, Connecticut, alongside Stryper and Steven Adler on March 25, 2023, but the venue indefinitely postponed the concert on March 2, citing its proximity to the twentieth anniversary of the fire.[98]

Others[edit]

41, a documentary about Nicholas O'Neill, the youngest victim of the fire, was screened at Rhode Island theaters in 2008.[99] 41 and a film based on O'Neill's play They Walk Among Us were aired by Rhode Island PBS in February 2013 in conjunction with the tenth anniversary of the fire.[100]

Gonsalves was inducted into the Rhode Island Radio and Television Hall of Fame in 2013.[101]

The Derderian brothers conducted their first television interview about the fire in 2021 for 48 Hours.[48] Some victims' families criticized the 48 Hours segment and the Derderians' involvement.[48]

Safety measures[edit]

Following the tragedy, Governor Donald Carcieri declared a moratorium on pyrotechnic displays at venues that hold fewer than 300 people.[76] The Rhode Island state fire code was changed after the fire to require every nightclub in the state with a capacity of over 150 people to have a sprinkler system installed.[3]

As numerous violations of existing codes contributed to the severity of the fire, there was immediate effort to strengthen fire code protections. Within weeks, the National Fire Protection Association committee met to regulate code for "assembly occupancies". Based upon its work, Tentative Interim Amendments (TIAs) were issued for the national standard "Life Safety Code" (NFPA 101), in July 2003. The TIAs required automatic fire sprinklers in all existing nightclubs and similar locations that accommodate more than 100 occupants, and all new locations in the same categories. The TIAs also required additional crowd manager personnel, among other things. These TIAs were subsequently incorporated into the 2006 edition of NFPA 101, along with additional exit requirements for new nightclub occupancies.[102] It is left for each state or local jurisdiction to legally enact and enforce the current code changes.

As a result of this and other similar incidents, fire chiefs, fire marshals and inspectors require trained crowd managers to comply with the International Fire Code, NFPA-101 Life Safety Code, NFPA-1 Fire Code and many local ordinances that address safety in public-assembly occupancies. However, fire professionals have few choices about what training should be provided and training programs are continually updated to incorporate new technologies as well as lessons learned from actual fire experiences.[103]

Legislation[edit]

Inspired by the fire, the Fire Sprinkler Incentive Act has been proposed United States Senate and House of Representatives since 2003.[104] The legislation would create a tax incentive for property owners to install fire sprinkler systems.[104] It was last introduced in the House in 2015 by then-U.S. Reps. James Langevin of Rhode Island and Tom Reed of New York.[104]

See also[edit]

- List of fireworks accidents and incidents

- List of nightclub fires

- 2003 E2 nightclub stampede, occurred three days prior to this event

Notes[edit]

- ^ 96 at the scene, 4 in hospitals

References[edit]

- ^ Augustine, Bernie (February 21, 2013). "The Station nightclub fire 10 years later: Healing continues as West Warwick, Rhode Island, takes next step in recovery". New York Daily News. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Parker, Paul Edward. "The Station Fire: Timeline of a tragedy". The Providence Journal. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Mooney, Tom. "Station tragedy leads to tougher fire code". The Providence Journal. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Grosshandler, William L.; Bryner, Nelson P.; Madrzykowski, Daniel M. "Report of the Technical Investigation of The Station Nightclub Fire (NIST NCSTAR 2), Volume 1". NIST.gov. National Institute of Standards and Technology. pp. 36–38. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ a b Donnis, Ian. "Beyond grief: Trying to make sense out of the Station tragedy". Providence Phoenix. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Powell, Michael; Lee, Christopher (February 24, 2003). "Devices Used at R.I. Club In Past". Washington Post. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Cromelin, Richard; Braxton, Greg (February 22, 2003). "Tragedy Catches Up to a Metal Band Past Its Prime". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c Segal, David (February 22, 2003). "Great White Fireworks Set Off a Controversy". Washington Post. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Axelrod, Jim (October 24, 2021). "The Station nightclub fire: What happened and who's to blame for disaster that killed 100?". 48 Hours. CBS News. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ "Great White: Billboard Hot 100". Billboard. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c Ratliff, Ben (February 22, 2003). "Fire in a nightclub: the band; group persevered by making circuit of smaller clubs". The New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Miller, G. Wayne. "How tragedy inspired one member of Great White". The Providence Journal. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ "Rhode Island Remembers Victims Of Deadly GREAT WHITE Concert Fire". Blabbermouth. February 24, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ "Club, band dispute permission to use fireworks - Feb. 22, 2003". www.cnn.com. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Vogt, Tom. "Memories sear survivor of fire that killed 100 in 2003". The Columbian. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Lewis, Richard. "Parents mourn loss of only child in nightclub fire, but cherish time they had after first near-death experience". New Bedford Standard-Times. The Associated Press. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Mello, Michael (March 17, 2003). "R.I. club survivors form friendships". Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 20, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Radio station to remain in fire lawsuits". UPI. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ "Clear Channel agrees to pay $22 million to nightclub fire victims". The Hour. February 14, 2008. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ Buote, Brenda. "Portraits of people who died in the R.I. nightclub fire". Boston.com. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Towne, Shaun (February 20, 2023). "Timeline: What happened the night of the Station nightclub fire?". WPRI.com. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Milkovits, Amanda. "20 years later, the effects of the Station nightclub fire still linger - The Boston Globe". Boston Globe. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Pemberton, Pat (July 15, 2013). "The Great White Nightclub Fire: Ten Years Later". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Murphy, Linda. "Station nightclub fire survivor tells how she's moved on in new book". Wicked Local. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ Killer Show chapter 12 "I'm With the Band" (pages 93-101).

- ^ a b c d Grosshandler, William L.; Bryner, Nelson P.; Madrzykowski, Daniel M. "Report of the Technical Investigation of The Station Nightclub Fire (NIST NCSTAR 2), Volume 1". NIST.gov. National Institute of Standards and Technology. pp. 39–40. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Mooney, Tom. "In West Warwick firefighters' hearts, the disaster isn't over". The Providence Journal. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Grosshandler, William L.; Bryner, Nelson P.; Madrzykowski, Daniel M. "Report of the Technical Investigation of The Station Nightclub Fire (NIST NCSTAR 2), Volume 1". NIST.gov. National Institute of Standards and Technology. pp. 61–63. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Doiron, Sarah; Montecalvo, Mike (February 20, 2023). "How a West Warwick restaurant became a triage center for burn victims". WPRI. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ a b Grosshandler, William L.; Bryner, Nelson P.; Madrzykowski, Daniel M. "Report of the Technical Investigation of The Station Nightclub Fire (NIST NCSTAR 2), Volume 1". NIST.gov. National Institute of Standards and Technology. pp. 43–44. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "20th anniversary of New England nightclub fire that killed 100". WCVB. February 20, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ "No relief from night of horror". Cranston Herald. February 25, 2003. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b "State supreme court to review penalty for employee deaths in R.I. fire - UPI.com". UPI. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "Workers comp. fine against Station Nightclub owners upheld". ABC6. March 29, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "The Station fire took emotional toll on survivors, study finds". BostonGlobe.com. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ "Tentative $30 million deal in R. I. nightclub fire". NBC News. February 2, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Bauder, David. "TV station that assigned reporter to cover his own nightclub raises ethical issue". New Bedford Standard-Times. Associated Press. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "Station Video Spurs Lawsuit - Pollstar News". Pollstar. March 14, 2006. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ a b "Nightclub owner resigns from WPRI television". Lewiston Sun Journal. Associated Press. July 1, 2003. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Elliott, Deni. "Ethics Matters". News Photographer. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. Retrieved December 7, 2007.

- ^ Butler, Brian (February 21, 2003). "Nightclub Fire Kills 39 People". CNN.

- ^ Kuntz, K.; Madrzykowski, Daniel M.; Bryner, Nelson P.; Grosshandler, William L. (June 30, 2005). "NIST Manuscript Publication Search". Nist.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ a b Grosshandler, William L.; Bryner, Nelson P.; Madrzykowski, Daniel M. "Report of the Technical Investigation of The Station Nightclub Fire (NIST NCSTAR 2), Volume 1". NIST.gov. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Lukasik, Tara. "Remembering the Station Nightclub Fire". International Code Council Building Safety Journal. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ Grosshandler, William L.; Bryner, Nelson P.; Madrzykowski, Daniel M. "Report of the Technical Investigation of The Station Nightclub Fire: Appendices (NIST NCSTAR 2), Volume 2". NIST.gov. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Lee, Christopher; Powell, Michael (February 26, 2003). "Grand Jury Convened to Probe Deadly R.I. Nightclub Fire". Washington Post. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ "3 indicted in R.I. rock concert fire - UPI Archives". UPI. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Farzan, Antonia Noori; Mooney, Tom. "The Derderians are on a 'white-wash tour' about The Station fire, says father who lost son". The Providence Journal. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Hotten, Jon (February 20, 2023). "The strange and terrible true story of Great White, and the Station nightclub fire". Loudersound. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Belluck, Pam (December 10, 2003). "3 Men Are Indicted in Fire At Rhode Island Nightclub". The New York Times. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ Tucker, Eric (June 26, 2008). "Foam company offers Station nightclub fire plaintiffs $6.3M settlement". The Sun Chronicle. The Associated Press. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c Peoples, Steve (May 10, 2006). "Prosecutor wants 10 years for Biechele". The Providence Journal. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013.

- ^ "DAN BIECHELE SPEAKS Pre-Sentencing Statement GREAT WHITE TOUR MANAGER Station Nightclub Fire RI". YouTube.

- ^ Perry, Jack (May 10, 2006). "Biechele gets 4 years to serve". The Providence Journal. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011.

- ^ Mehren, Elizabeth (May 11, 2006). "Fury, Tears and 4-Year Term in Deadly Blaze". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ "Band manager who ignited deadly Rhode Island nightclub fire freed from prison". statesboroherald.com.

- ^ "Manager Sentenced for Rhode Island Nightclub Fire". The New York Times. May 10, 2006. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Tucker, Eric. "Many families of Station fire victims supporting parole for band manager". New Bedford Standard-Times. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ "Band manager who ignited R.I. club fire is freed". NBC News. The Associated Press. March 19, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Ziner, Karen Lee (February 12, 2013). "After prison, Biechele rebuilding life in Fla". The Providence Journal. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Breton, Tracy (September 21, 2006). "Derderians will plead; AG says he opposes sentencing deal". The Providence Journal.

- ^ Belluck, Pam (September 21, 2006). "2 Brothers to Plead No Contest in R.I. Nightclub Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Holusha, John (September 29, 2006). "Judge Accepts Plea Deal in Rhode Island Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ Tucker, Eric (January 17, 2008). "Co-owner of R.I. club where 100 died to be released early". The Boston Globe. Associated Press.

- ^ "Band to pay $1M in case over deadly club fire". Archived from the original on September 3, 2008. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ^ Tucker, Eric (September 2, 2008). "Great White offers $1M to settle fatal fire suits". Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

Great White's insurer is covering the settlement. The insurer has previously said that $1 million was the maximum amount of the band's insurance policy.

- ^ "Derderians reach settlement in nightclub fire". WJAR. September 3, 2008. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "Governments offer $20 million in RI nightclub fire". Archived from the original on August 22, 2008. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ^ "Packaging company settles in R.I. nightclub fire". NBC News. The Associated Press. June 13, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Estes, Andrea (February 2, 2008). "Tentative deal set in R.I. fire case". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on July 6, 2010 – via Wayback Machine.

- ^ "JBL Settles On Station Fire Lawsuit". Archived from the original on May 6, 2008. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- ^ a b PBN staff (May 27, 2008). "McLaughlin & Moran, Anheuser-Busch offer $21M settlement in Station fire case". Providence Business News. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

'Under the proposal, the carriers would pay $16 million for settlement of all claims against McLaughlin & Moran.' The other $5 million would be paid by St. Louis-based Anheuser-Busch, the nation's largest brewer.

- ^ "Home Depot Settles In R.I. Nightclub Fire". Associated Press. February 13, 2008. Archived from the original on February 1, 2008. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

Home Depot Inc. and a Connecticut insulation company have tentatively agreed to a $5 million settlement in lawsuits brought by survivors of a 2003 nightclub fire and relatives of the 100 people killed, a lawyer for the families said Wednesday.

- ^ PBN staff (February 13, 2008). "WHJY, Clear Channel offer $22M Station fire settlement". Providence Business News. Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

Local radio station 94 WHJY-FM and parent company Clear Channel Communications Inc. (NYSE: CCU) have reached a tentative $22 million settlement of lawsuits brought by victims and survivors of the fatal nightclub fire five years ago in West Warwick, Clear Channel said today.

- ^ Henson, Shannon. "Foam Company Settles Club Fire Claims". Law360. LexisNexis. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ a b "Service recalls victims of nightclub fire - Feb. 25, 2003". CNN. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ "Families visit scene of deadly nightclub fire - Feb. 24, 2003". www.cnn.com. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b "Concert for nightclub fire survivors nets $25K". The Worcester Telegram & Gazette. Associated Press. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ "Governor McKee Statement on 20th Anniversary of Station Nightclub Fire | Governor's Office, State of Rhode Island". State of Rhode Island. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ Laguarda, Ignacio (March 22, 2015). "Station Nightclub Fire Memorial On Track For 2016 Opening". Hartford Courant. Associated Press. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ^ "Timeline: Station Nightclub Fire, 15 year anniversary". Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ "'Pokemon Go' stop at site of deadly nightclub fire upsets families". WCVB Boston. August 9, 2016. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016.

- ^ "Station nightclub site will no longer be Pokemon Go destination". The Providence Journal. The Associated Press. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "Our Mission". The Station Fire Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on July 11, 2007. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ^ Smith, Michelle R. (December 28, 2012). "Owner of burned RI club donates land for memorial". AP. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ^ Beacon staff writers (April 5, 2016). "Job Lot customers respond to Station Fire Memorial drive". Warwick Beacon. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ^ "SFM Park". The Station Fire Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on May 26, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ^ Towne, Shaun (May 21, 2017). "Memorial park dedicated to victims of Station Nightclub Fire". WPRI. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c Arsenault, Paul (July 31, 2003). "Great White: Performing again is the right thing". The Providence Journal. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ a b "Providence nightclub fire charity rebuffs Great White singer". MassLive. The Associated Press. January 18, 2013. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ Mervis, Scott (March 25, 2005). "After the fire: Great White, survivors live with the horror of Rhode Island tragedy". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ Episode Transcripts (February 9, 2005). "Rhode Island Club Fire Tragedy Revisited with Members of Rock Band Great White". Larry King Live. CNN. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ^ a b Shaw, Zach (December 14, 2011). "Now There's Two Versions Of Great White | Metal Insider". Metal Insider. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c Christopher, Michael (August 4, 2015). "After The Fire: Feelings mixed and emotions high as Jack Russell's Great White return to New England". Vanyaland. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ a b c Valencia, Milton J.; Arsenault, Mark. "A decade of disconnect, drugs, decline". Boston.com. Boston Globe. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ "Great White And Jack Russell Reach Agreement Over Use Of Band Name". Sleaze Roxx. July 23, 2013. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ "Great White singer's fire memorial concert nixed". Los Angeles Times. January 18, 2013. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013.

- ^ Doiron, Sarah (March 3, 2023). "Mohegan Sun postpones Great White concert booked close to Station fire anniversary". WPRI. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ "Documentary on youngest Station victim to be aired". The Sun Chronicle. February 20, 2008. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ "Films by RIC Alum Are Among Station Nightclub Fire Tributes". Rhode Island College. February 12, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ "2013 Inductees". rirtvhof.com. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ "Station Night Club Fire". nfpa.org. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ^ "Crowd Manager Training". www.iafc.org. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c Brown, Jeremy (September 24, 2015). "Langevin introduces fire sprinkler act". WPRI.com. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

Further reading[edit]

- James, Scott (2020). Trial by Fire: A Devastating Tragedy, 100 Lives Lost, and a 15-Year Search for Truth. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 9781250131263. OCLC 1157465705. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Barylick, John (2012). Killer Show: The Station Nightclub Fire, America's Deadliest Rock Concert. New Hampshire: University Press of New England. ISBN 9781611682045. OCLC 774697199. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

External links[edit]

- The Boston Globe: "Portraits of People Who Died in the R.I. Nightclub Fire" (2003)

- National Fire Protection Association web page "Nightclubs/assembly occupancies": Includes a report on the fire, links to nightclub safety tips, information on safe use of pyrotechnics, and other relevant information.

- NIST simulations of the fire: without sprinklers; with sprinklers

- Full NIST government investigation

- Guide to the Station Nightclub Victims' Collection from the Rhode Island State Archives Archived August 31, 2018, at the Wayback Machine