Sanford, Maine | |

|---|---|

Sanford in 2014 | |

| Nickname: The heart of York County | |

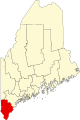

Location of city of Sanford in map of Maine | |

| Coordinates: 43°26′2″N 70°45′51″W / 43.43389°N 70.76417°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Maine |

| County | York |

| Settled | 1739 |

| Incorporated | Town: February 27, 1768 City: January 1, 2013 |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Council/Mayor |

| • Mayor | Becky A. Brink |

| • City Council |

|

| • City Manager | Steven R. Buck |

| Area | |

| • Total | 48.75 sq mi (126.27 km2) |

| • Land | 47.79 sq mi (123.78 km2) |

| • Water | 0.96 sq mi (2.50 km2) |

| Elevation | 262 ft (80 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 21,982 |

| • Density | 459.97/sq mi (177.59/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 04073 and 04083 |

| Area code | 207 |

| FIPS code | 23-65760 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0582712 |

| Website | www.sanfordmaine.org |

Sanford is a city in York County, Maine, United States. The population was 21,982 in the 2020 census, making it the seventh largest municipality in the state.[2] Situated on the Mousam River, Sanford includes the village of Springvale. The city features many lakes in wooded areas which attract campers.

Sanford is part of the Portland–South Portland–Biddeford, Maine metropolitan statistical area.

On November 6, 2012, Sanford voters approved a new charter to re-incorporate Sanford as a city and replace the town meeting format with a city council/mayor/strong manager form of government, along with other changes. The new charter took effect on January 1, 2013.[3] Sanford's new charter provides that the first mayor would be appointed from the ranks of Sanford's seven city councilors and serve interim for one-year period. On January 8, 2013, Maura A. Herlihy was appointed as Sanford's first mayor.[4]

In 2014, an elected-at-large mayor took office. On November 5, 2013, Thomas Cote was elected as mayor.[5] Beginning in 2016, the mayoral position began being elected at-large every two years during legislative election cycles.

History[edit]

Sanford is in the western portion of a tract of land purchased in 1661 from Abenaki Chief Fluellin by Major William Phillips, an owner of mills in Saco. First called Phillipstown, it was willed in 1696 by Mrs. Phillips to her former husband's son, Peleg Sanford.[6] Settlement was delayed, however, by hostilities during the French and Indian Wars. In 1724, Norridgewock, an Abenaki stronghold on the Kennebec River, was destroyed by a Massachusetts militia. Subsequently, the region became less dangerous for white settlers, and Sanford was first settled in 1739. Incorporated a town in 1768, it was named after Peleg Sanford. Until 1794, Alfred was the town's North Parish.[7]

The Mousam River provided water power for industry. In 1745, Capt. Market Morrison built a sawmill above Springvale. Following the Civil War, Sanford developed into a textile manufacturing center, connected to markets by the Portland and Rochester Railroad. Factories were built at both Springvale and Sanford villages. Products included cotton and woolen goods, carpets, shoes and lumber.[8]

In 1867, British-born Thomas Goodall established the Goodall Mills at Sanford, after selling another mill in 1865 at Troy, New Hampshire which made woolen blankets contoured to fit horses. His factory beside the Mousam River first manufactured carriage robes and blankets. It would expand to make mohair plush for upholstering railroad seats, carpets, draperies, auto fabrics, military uniform fabric and Palm Beach fabric for summer suits.[9]

The company's textiles were known for brilliant and fast colors and found buyers worldwide. From 1880 to 1910, the mill town's population swelled from 2,700 to over 9,000, some living in houses built by the company and sold to workers at cost. In 1914, the Goodall family built Goodall Park, a 784-seat roofed stadium, now a treasured historic site. They also helped build the library, town hall, hospital, airport, and golf club. A bronze statue was erected by the citizens of Sanford in 1917 to the memory of Thomas Goodall. His effigy has a place of honor in Central Park.[9] George and Henrietta Goodall's daughter, Marion C. Goodall Marland, and her husband William Marland continued the Goodall family philanthropy. A dormitory at Nasson College bears the Marland's name.

In 1954, Burlington Mills, then the nation's largest textile firm, bought Sanford Mills. After moving the looms to its Southern plants, Burlington closed Sanford Mills—leaving 3,600 unemployed and 2,000,000 square feet (190,000 m2) of empty mills. Local business owners began traveling the northeast, enticing employers to move to the area. In November 1955, NBC's Armstrong Circle Theatre dramatized Sanford's comeback on television in “The Town that Refused to Die”,[10] starring Darren McGavin and Jason Robards. The story was later featured in LIFE magazine's feature on "Community Boosters" on August 5, 1957.[11] It now has diversified industries, including manufacturing and biotech.[12] When the federal government offered money in the 1960s for urban renewal to rehabilitate aging or blighted districts, more than thirty Sanford structures were razed. In Springvale, three of four corners were leveled. Nevertheless, much fine architecture from the town's prosperous mill era survived.[9]

Sanford was the home of Belle Ashton Leavitt, the third woman attorney admitted to the Maine Bar Association. Leavitt was admitted to the Bar in 1900.[13] Leavitt operated in partnership with attorney Fred J. Allen, her brother-in-law (Allen was married to Belle's sister Ida Leavitt), and member of the Maine Legislature.[14]

The town gained national notoriety in 1984, when Scott Waterhouse, then age 18, strangled 12-year-old Gycelle Cote. Rumors of Satanism surrounded the case, and some of Waterhouse's personal belongings were deemed to be occult in nature.[15] These included a copy of The Satanic Bible and a notebook carrying Satanic drawings and poetry. The furor culminated in several tabloid stories, national television coverage, and at least one headline referring to the town as "Terrortown!".[citation needed]

The town again gained national notoriety on November 9, 2009, when the Amber Alert system was first used in the state for 2-year-old Hailey Traynham, abducted by her father.[16]

In 2003, Maine voters rejected a proposal to build a $650 million casino in South Sanford. The 362-acre (1.46 km2) development, ostensibly owned by the Penobscot and Passamaquoddy nations, would have included 4,000 slot machines, 180 gaming tables, a hotel, a 60,000-square-foot (5,600 m2) convention center and an 18-hole golf course. Proponents argued it would add 4,700 permanent jobs and direct 25% of its revenue to the state. Detractors predicted higher crime, traffic and an erosion of Maine's quality of life.[17]

On June 23, 2017, the largest mill fire Sanford firefighters have ever battled erupted. The flaming five-story back building of the former Stenton Trust Mill complex at 13 River Street brought more than 100 firefighters from 20 communities to battle the blaze.[18] The 294,000-square-foot (27,300 m2) complex, which was built in 1922 as a textile mill, includes two five-story brick and concrete buildings and a one-story connecting structure. Two days later, three boys from Sanford, two 13-year-olds and a 12-year-old, were charged with felony arson in connection with the fire.[19][20] They pleaded guilty to criminal mischief and were placed on probation for a year.[21][22]

-

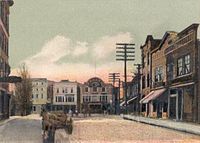

View of Sanford c. 1912

-

Central Square c. 1905

-

Goodall Mansion in 1910

-

Leavitt & Company c. 1892

Geography[edit]

Sanford is located at 43°26′23″N 70°46′23″W / 43.43972°N 70.77306°W (43.439925, −70.773304).[23] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 48.75 square miles (126.26 km2), of which 47.78 square miles (123.75 km2) is land and 0.97 square miles (2.51 km2) is water.[24] Located near foothills, Sanford is drained by the Mousam River. Mt. Hope, at an elevation of 680 feet (207 m) above sea level, is the city's highest point. The lowest elevation, which is approximately 140 feet (42.7 m) above sea level, is on the Mousam River at Old Falls Pond as it flows into Kennebunk.

Sanford borders the towns of Shapleigh, Acton, Alfred, Kennebunk, Wells, North Berwick, and Lebanon.

-

Number One Pond

-

Moon over Gowen Park

-

MacDougal Pond

Climate[edit]

The climate is humid continental, similar to that of nearby towns such as Concord, New Hampshire. The Köppen classification is Dfb.

| Climate data for Sanford (1953–2012 normals; extremes 1953–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 68 (20) |

74 (23) |

88 (31) |

92 (33) |

97 (36) |

97 (36) |

98 (37) |

101 (38) |

95 (35) |

89 (32) |

75 (24) |

73 (23) |

101 (38) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 52 (11) |

54 (12) |

65 (18) |

79 (26) |

88 (31) |

91 (33) |

92 (33) |

90 (32) |

87 (31) |

77 (25) |

67 (19) |

56 (13) |

94 (34) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 32.5 (0.3) |

36.1 (2.3) |

44.8 (7.1) |

57.8 (14.3) |

69.7 (20.9) |

78.0 (25.6) |

82.7 (28.2) |

81.3 (27.4) |

73.1 (22.8) |

61.9 (16.6) |

48.7 (9.3) |

36.8 (2.7) |

58.6 (14.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 11.6 (−11.3) |

13.8 (−10.1) |

23.1 (−4.9) |

32.8 (0.4) |

42.9 (6.1) |

52.4 (11.3) |

57.6 (14.2) |

56.1 (13.4) |

48.4 (9.1) |

37.6 (3.1) |

29.8 (−1.2) |

18.2 (−7.7) |

35.4 (1.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −9 (−23) |

−6 (−21) |

3 (−16) |

21 (−6) |

30 (−1) |

41 (5) |

48 (9) |

45 (7) |

34 (1) |

25 (−4) |

14 (−10) |

1 (−17) |

−12 (−24) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −28 (−33) |

−25 (−32) |

−13 (−25) |

10 (−12) |

22 (−6) |

31 (−1) |

38 (3) |

31 (−1) |

23 (−5) |

12 (−11) |

−1 (−18) |

−20 (−29) |

−28 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.66 (93) |

3.69 (94) |

4.43 (113) |

4.21 (107) |

4.03 (102) |

3.87 (98) |

3.76 (96) |

3.60 (91) |

3.83 (97) |

4.50 (114) |

4.98 (126) |

4.33 (110) |

48.88 (1,242) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 16.4 (42) |

12.2 (31) |

11.8 (30) |

2.3 (5.8) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

2.1 (5.3) |

14.1 (36) |

59.3 (151) |

| Source 1: Desert Research Institute[25] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA[26] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[edit]

- See also Sanford (CDP), Maine, South Sanford, Maine, and Springvale, Maine for village demographics.

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 1,799 | — | |

| 1800 | 1,363 | −24.2% | |

| 1810 | 1,492 | 9.5% | |

| 1820 | 1,831 | 22.7% | |

| 1830 | 2,327 | 27.1% | |

| 1840 | 2,233 | −4.0% | |

| 1850 | 2,330 | 4.3% | |

| 1860 | 2,221 | −4.7% | |

| 1870 | 2,397 | 7.9% | |

| 1880 | 2,734 | 14.1% | |

| 1890 | 4,201 | 53.7% | |

| 1900 | 6,078 | 44.7% | |

| 1910 | 9,049 | 48.9% | |

| 1920 | 10,691 | 18.1% | |

| 1930 | 13,392 | 25.3% | |

| 1940 | 14,886 | 11.2% | |

| 1950 | 15,177 | 2.0% | |

| 1960 | 14,962 | −1.4% | |

| 1970 | 15,812 | 5.7% | |

| 1980 | 18,020 | 14.0% | |

| 1990 | 20,463 | 13.6% | |

| 2000 | 20,806 | 1.7% | |

| 2010 | 20,798 | 0.0% | |

| 2020 | 21,982 | 5.7% | |

| [27][28][29] | |||

2010 census[edit]

As of the census[30] of 2010, 20,798 people, 8,500 households, and 5,417 families resided in the city. The population density was 435.3 inhabitants per square mile (168.1/km2). There were 9,452 housing units at an average density of 197.8 per square mile (76.4/km2). The city's racial makeup was 94.7% White, 0.6% African American, 0.4% Native American, 2.0% Asian, 0.3% from other races, and 2.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race made up 1.6% of the population.

There were 8,500 households, of which 30.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.7% were married couples living together, 13.1% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.9% had a male householder with no wife present, and 36.3% were non-families. Of all households, 28.9% were made up of individuals, and 11.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.41 and the average family size was 2.91.

The median age in the city was 40.5 years. 22.6% of residents were under the age of 18; 8.2% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 25% were from 25 to 44; 29% were from 45 to 64, and 15.1% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.9% male and 52.1% female.

2000 census[edit]

As of the census[31] of 2000, there were 20,806 people, 8,270 households, and 5,449 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 435.3 inhabitants per square mile (168.1/km2). There were 8,807 housing units at an average density of 184.3 per square mile (71.2/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 95.68% White, 0.44% Black or African American, 0.31% Native American, 2.07% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.27% from other races, and 1.21% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.96% of the population.

There were 8,270 households, out of which 33.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.5% were married couples living together, 12.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.1% were non-families. Of all households, 27.6% were made up of individuals, and 11.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.48 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the CDP the population was spread out, with 26.7% under the age of 18, 8.1% from 18 to 24, 29.0% from 25 to 44, 21.8% from 45 to 64, and 14.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.0 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $34,668, and the median income for a family was $43,021. Males had a median income of $33,115 versus $24,264 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $16,951. About 11.1% of families and 12.8% of the overall population were below the poverty line, including 17.0% of those under age 18 and 11.2% of those aged 65 or over.

Voter registration

| Voter Registration and Party Enrollment as of November 2012[32] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Total Voters | Percentage | |||

| Unenrolled | 5,496 | 40.82% | |||

| Democratic | 4,546 | 33.76% | |||

| Republican | 3,003 | 22.30% | |||

| Green Independent | 417 | 3.09% | |||

| Total | 13,462 | 100% | |||

Fire department[edit]

Sanford citizens are protected by Firefighter/EMT's working out of three fire stations located in Springvale, South Sanford, and Downtown Sanford. 3 Engines, 1 Ladder, and 1 Rescue are staffed 24 hours a day; 365 days a year. Authorized strength is 45 full-time fire personnel. SFD also provides Emergency Medical Services. All firefighters are required to have a Maine EMS license ranging from EMT-Basic to Paramedic. In 2007 SFD responded to 1,150 Fire Runs & 2,515 Medical Runs for a total of 3,665 emergencies.[citation needed]

School system[edit]

In 2018, Hutter Construction Co. workers built a new high school on a 127-acre campus in the center of town.[33] The construction cost was billed at $103 million, with the state covering the majority of the cost. It is a career-focused school,[34] separated into four wings,[35] in which students select specialized courses geared towards their preferred future career.

Sites of interest[edit]

- Louis B. Goodall Memorial Library

- Sanford-Springvale Historical Society & Museum

- Goodall Park - Baseball stadium home to the Sanford Mainers, two-time champions of the New England Collegiate Baseball League

- Mousam River

Events[edit]

- Sanford International Film Festival—an annual event that specializes in independent film

Notable people[edit]

- Frank Augustus Allen, mayor of Cambridge, Massachusetts (1877)

- Randy Brooks, musician

- Michael Richard Cote, Bishop of Norwich, Connecticut

- Nick Curran, musician

- Vic Firth, musician, businessman

- Louis B. Goodall, businessman, U.S. congressman

- Rachel Griffin-Accurso, better known as Ms. Rachel, American YouTuber, social media personality, songwriter, and educator, raised in Sanford

- Jane Lord Hersom (1840–1928), physician, suffragist

- Sumner Increase Kimball, organizer of the United States Life-Saving Service, founder of Coast Guard Academy

- Peter Kostis, golf instructor, sportscaster

- Raymond Luc Levasseur, member of the United Freedom Front

- Franz Lidz, journalist and author of the memoir Unstrung Heroes

- Mike McGinnis, composer, musician

- Patrick James McGinnis, investor, author

- Freddy Parent, Major League Baseball shortstop (1899–1911)

- Lawrence Lee Pelletier, 16th president of Allegheny College

- Amédée Wilfrid Proulx, Catholic bishop

- Joe Riggs, mixed martial arts fighter, UFC veteran

- Rachel Schneider Olympic Runner

- Charles A. Shaw, 19th-century politician, inventor

- John Storer, the namesake of Storer College

- John Tuttle, Maine state legislator

References[edit]

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Sanford city, Maine". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Shawn P. "Voter turnout the largest in years Town clerk releases Sanford's official election results". fosters.com. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ Writer, Ellen W. ToddSanford News. "Herlihy is city's first mayor". fosters.com. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Cote is Sanford's first popularly elected mayor". November 5, 2013.

- ^ Edwin Emery, William Morrell Emery, The History of Sanford, Maine 1661-1900, "Colonial Settlement" 1901 Archived 2007-09-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Coolidge, Austin J.; John B. Mansfield (1859). A History and Description of New England. Boston, Massachusetts: A.J. Coolidge. p. 291.

coolidge mansfield history description new england 1859.

- ^ Varney, George J. (1886), Gazetteer of the state of Maine. Sanford, Boston: Russell

- ^ a b c Emery, Edwin; William Morrell Emery (1901). The History of Sanford, Maine 1661-1900. Boston, Massachusetts: compiler. pp. 300–307.

History of Maine.

- ^ "Armstrong Circle Theatre (1950–1963): The Town That Refused to Die". www.imdb.com. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ^ "Community Boosters in Bootstrap Booms, Life Magazine, Aug 5, 1957". books.google.com. August 5, 1957. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ^ "Sanford Regional Economic Growth Council". sanfordgrowth.com. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ^ "LawInterview". www.lawinterview.com. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Lawyer Fred J. Allen and partner Belle Leavitt". mainememory.net. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Murder in Maine mixed Satan worship and drugs". upi.com. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Missing 2-year-old Maine girl found". bangordailynews.com. November 10, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Boston.com / News / Local / Mass. / Casino plan for Maine rejected by wide margin". www.boston.com. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ Keyes, Bob (June 23, 2017). "More than 100 firefighters battle flames that engulf Sanford mill". Portland Press Herald. Press Herald. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ "3 boys set fire to mill, 2 missing men found safe, officials say". WGME13. Sinclair Broadcast Group. June 26, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ Murphy, Edward (July 27, 2017). "Three boys charged in Sanford mill fire continue to be evaluated". Portland Press Herald. Press Herald. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ "Boys get probation for setting massive Sanford mill fire". WGME13. Sinclair Broadcast Group. October 12, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ Murphy, Edward (October 12, 2017). "Two of three boys charged in Sanford mill fire plead guilty to minor offense". Portland Press Herald. Press Herald. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ "Desert Research Institute".

- ^ "NOAA Gray".

- ^ https://www.census.gov/population/www/censusdata/cencounts/files/me190090.txt [bare URL plain text file]

- ^ Bureau, U.S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "University of Virginia Library". mapserver.lib.virginia.edu. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Registration and Party Enrollment Statistics as of November 6, 2012" (PDF). Maine Bureau of Corporations.

- ^ "Sanford High School Archives". October 12, 2018.

- ^ "About Our School Home Page". www.edlinesites.net. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013.

- ^ "After delays, crime, Sanford getting ready to open state's first $100M high school". August 28, 2018.