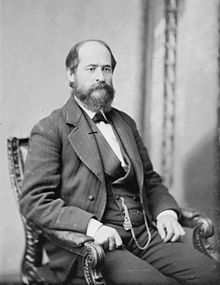

Richard P. Bland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Missouri | |

| In office March 4, 1873 – March 3, 1895 | |

| Preceded by | John B. Clark, Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Joel D. Hubbard |

| Constituency | 5th district (1873–83) 11th district (1883–93) 8th district (1893–95) |

| In office March 4, 1897 – June 15, 1899 | |

| Preceded by | Joel D. Hubbard |

| Succeeded by | Dorsey W. Shackleford |

| Constituency | 8th district |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Richard Parks Bland August 19, 1835 Hartford, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | June 15, 1899 (aged 63) Lebanon, Missouri, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Virginia Elizabeth Mitchell (1873–1899; his death); 9 children |

| Alma mater | Hartford College (Kentucky) |

| Signature | |

Richard Parks Bland (August 19, 1835 – June 15, 1899) was an American politician, lawyer, and educator from Missouri. A Democrat, Bland served in the United States House of Representatives from 1873 to 1895 and from 1897 to 1899,[1] representing at various times the Missouri 5th, 8th and 11th congressional districts. Nicknamed "Silver Dick" for his efforts to promote bimetallism, Bland is best known for the Bland–Allison Act.

Born in Kentucky, he established a legal practice in Utah Territory after working as a miner and schoolteacher. He served as the treasurer of Carson County from 1860 to 1864 during the peak years of the Comstock Lode mining rush. He settled in Missouri in 1865 and established a legal practice in Lebanon, Missouri. He was elected to the House of Representatives in 1872 and quickly established himself as a leading advocate of the free silver movement. He sponsored the Bland–Allison Act, which required the United States Department of the Treasury to buy a certain amount of silver and put it into circulation as silver dollars.[2] He also established himself as an anti-imperialist. Bland lost re-election in the 1894 election but won his seat back in 1896.

Bland was a leading candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1896, though he expressed reluctance about running for president. His marriage to a Catholic woman engendered opposition from the anti-Catholic elements of the party. Bland received the most votes on the first three ballots of the 1896 Democratic National Convention, but not enough to win the necessary majority. William Jennings Bryan, who also favored bimetallism, won the Democratic nomination on the fifth ballot and went on to lose to Republican William McKinley in the 1896 presidential election. After the convention, Bland served in the House from 1897 to his death in 1899.

Early life and education[edit]

Bland was born near Hartford, Ohio County, Kentucky to Stoughton Edward and Mary P. (Nall) Bland.[3] His father was a descendant of one of the First Families of Virginia, including statesman and Continental Congress member Richard Bland.[4] The Blands and Nalls were among the early families to emigrate from Virginia with Daniel Boone into the Kentucky wilderness.[3] Despite the family pedigree and wealth in Virginia, Richard and his three siblings were raised in relative poverty on his parents' small farm.[4] In 1842, when Richard Bland was seven years old, the situation was exacerbated by the unexpected death of his father.[3] His mother's death followed in 1849, leaving the young teenager an orphan and forcing Bland to hire himself out as a farm laborer to survive.[4][5] Despite growing up poor, he was able to attend Hartford College and graduate with a teacher's certificate. Bland then taught school in his hometown for two years before moving to Wayne County, Missouri at age 20, in 1855.

His first time of residence in Missouri was brief, Bland teaching just one term at a school in Patterson, Missouri before heading further west to California. While there he began to study law.[6] He then moved to the western portion of the Utah Territory, part of present-day western Nevada, where he taught school, and tried his hand at prospecting and mining.[5] It appears, from a eulogy delivered in Congress, that while in the West Bland was also involved in conflict with Native Americans on multiple occasions, although few details are known.[4] While teaching school he continued to study law and after passing the bar began practicing in Virginia City and Carson City.[6] It was during his time in California and Nevada he developed a lifelong interest in mining, silver in particular.[4]

Political career[edit]

Richard P. Bland's first elected office was treasurer of Carson County, Utah Territory from 1860 to 1864, the height of the Comstock Lode mining rush.[6] Left without a job following Nevada's statehood and government reorganizing, in 1865 Bland returned to Missouri and began the practice of law with his brother Charles in the town of Rolla.[3] The siblings remained in practice together until 1869 when he moved to Lebanon, Missouri, seeing the town as more commercially viable because a predecessor of the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad had recently laid track through the town.

In 1872, he was elected as a Democrat to the United States House of Representatives in the 43rd Congress. From the start of his tenure, silver would be an issue of great importance to Bland. The Panic of 1873 and Coinage Act of 1873 hit Missouri and other Midwestern farmers particularly hard, leading to foreclosures and closing of businesses dependent on agriculture.[7] In 1878, along with Iowa Republican William Allison he sponsored the Bland–Allison Act. This act mandated the use of both gold and silver as U.S. currency and allowed silver to be purchased at market rates, metals to be minted into silver dollars, and required the US Treasury to purchase between $2 million and $4 million of silver each month from western mines.[8] Vetoed by President Rutherford Hayes, Congress voted again on the measure overriding the President. The act stood until President Grover Cleveland repealed the act in 1893.[9]

Bland's nicknames -- "The Great Commoner" and "Silver Dick"— reflected his efforts to help both the common man and the silver miners. His 25-year campaign for a bimetallic standard made him a friend and advocate for agriculture and western miners. However, Bland was far more than a one-issue legislator. He frequently involved himself in debates on tariff issues, government bonds, and taxation of the citizenry. Bland strongly opposed Reconstruction Era electoral commissions and bitterly opposed the use of U.S. Marshals or Federal troops at polling places.[4] In matters of foreign policy Bland was an anti-imperialist.

He was re-elected to the House ten times, narrowly defeated in 1894, regained his seat in 1896, was re-elected in 1898, and died in office in 1899. While a member of the House he was chairman of the Committee on Mines and Mining in the 44th Congress.[6] Bland was chairman of the Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures in the 48th Congress, 49th Congress, 50th Congress, 52nd Congress, and 53rd Congress.[6]

Election of 1896[edit]

Richard Bland was a strong, if reluctant, candidate for United States President in 1896. He is quoted as saying "I have no desire in this direction. I have no ambition for this nomination and I am afraid my friends, thrusting my personality into this contest may confuse the greater question."[4] That question of course, like most tied to Bland, was currency and bimetalism. Rather than travel to the Democratic Convention in Chicago, Illinois Bland chose to remain on his 160-acre farm near Lebanon, Missouri as the political drama played out. At first the convention balloting seemed to be going Bland's way. He beat William Jennings Bryan 236 to 137 on the first ballot, 281 to 197 on the second, and 291 to 219 on the third. However, none were of the two-thirds margin to secure the nomination outright. By this time, the full impact of Bryan's Cross of Gold speech began to be felt and understood by the delegates. Bryan took the lead on the fourth ballot 280–241. Bland, not wishing to risk a split party, sent a telegram to his supporters in Chicago throwing his support behind Bryan saying "Put the cause above the man."[4] With that, the fifth ballot was a mere formality, with Bryan claiming a 652 to 11 victory. There still existed the possibility of Bland on the ticket as candidate for Vice President. He trailed considerably behind on the first ballot, but gained steam to win the second and third balloting, although again by not enough margin to earn the nomination. Bland at this time, never enthralled with the idea in the first place, declined his name being considered in any further balloting, paving the way for Arthur Sewall to become Bryan's ticketmate.

Death[edit]

Richard P. Bland died at his home in Lebanon, Missouri on June 15, 1899. He had been in failing health for some years,[4] and in the spring of 1899 returned to Lebanon from Washington, D.C. to recover from a severe throat infection, but his condition only worsened.[5] He is buried in the Calvary Catholic Cemetery in Lebanon, Missouri. A crowd of several thousand flocked to the small Missouri Ozarks town to attend Bland's funeral.[4]

Personal life[edit]

Richard Bland married Virginia Elizabeth Mitchell of Rolla on December 19, 1873.[10] Mrs. Bland was the daughter of Confederate General Ewing Young Mitchell.[4] The couple had a total of nine children,[4] six that were still living at the time of his death: Theodric, Ewing, Frances, John, George, and Virginia. The Blands marriage was somewhat unusual for the time period, he being Protestant and son of a trained Presbyterian minister, and she being Catholic.[4] The children were raised in the Catholic faith, something which along with his marriage led to derision and bigotry by opponents during his 1896 bid for the Democratic presidential nomination.[4] Replying to critics, Bland stated "Yes my wife is a Roman Catholic and I am a Protestant, and shall live and die one; but my regret is that I am not half such a Christian as the woman who bears my name and is the mother of my children."[4]

Bland was a Freemason, a member of Lodge 231 in Rolla, Missouri.[11] One of his siblings, brother Charles C. Bland, was also involved with the legal profession, eventually serving as a judge in the Missouri 18th Judicial Circuit.[3] Bland's brother-in-law Ewing Young Mitchell, Jr., with his help became a U.S. Senate page in 1886 and would remain in politics throughout his life, eventually becoming assistant Secretary of Commerce under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.[12]

Honors[edit]

Richard P. Bland is the namesake of Bland, Missouri.[13]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Honor "Silver Dick" Bland's Memory" (PDF). The New York Times. April 8, 1900. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ Ari Arthur Hoogenboom, Rutherford B. Hayes: Warrior and President (1995) pp 96-98

- ^ a b c d e "A Reminiscent History of the Ozark Region: comprising a condensed general history, a brief descriptive history of each county, and numerous biographical sketches of prominent citizens of such counties.". Goodspeed Brothers Publishers, 1894. via AccessGenealogy.com. July 6, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Memorial addresses on the life and character of Richard P. Bland". United States 56th Congress via Government Printing Office. 1900. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c Christensen, Lawrence O.,Dictionary of Missouri Biography, University of Missouri Press, 1999

- ^ a b c d e "Richard P. Bland Congressional biography". United States Congress via website. 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ Irwin Unger, The Greenback Era: A Social and Political History of American Finance, 1865-1879 (1964) pp 356-65

- ^ Acts, Bills, and Laws, 1878.U.S. History. March 14th <http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h718.html>

- ^ Agger, Eugene E. (1918). "Our Large Change: The Denominations of the Currency". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 32 (2): 257–277. doi:10.2307/1885428. JSTOR 1885428.

- ^ Brown, Frank (September 26, 2006). "Virginia Elizabeth Mitchell Bland bio". Find A Grave.com. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ Denslow, William R. (1957). 10,000 Famous Freemasons. Columbia, Missouri, USA: Missouri Lodge of Research.

- ^ "Papers of Ewing Y. Mitchell, Jr" (PDF). University of Missouri. 2014. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ Eaton, David Wolfe (1916). How Missouri Counties, Towns and Streams Were Named. The State Historical Society of Missouri. pp. 169.