Richard Morris Hunt | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 31, 1827 Brattleboro, Vermont, U.S. |

| Died | July 31, 1895 (aged 67) Newport, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Alma mater | École des Beaux-Arts |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse | Catharine Clinton Howland |

| Buildings | John N. A. Griswold House Chateau-sur-Mer New York Tribune Building William K. Vanderbilt House Marble House Biltmore Estate |

| Signature | |

Richard Morris Hunt (October 31, 1827 – July 31, 1895) was an American architect of the nineteenth century and an eminent figure in the history of architecture of the United States. He helped shape New York City with his designs for the 1902 entrance façade and Great Hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Fifth Avenue building, the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty (Liberty Enlightening the World), and many Fifth Avenue mansions since destroyed.[1]

Hunt is also renowned for his Biltmore Estate, America's largest private house, near Asheville, North Carolina, and for his elaborate summer cottages in Newport, Rhode Island, which set a new standard of ostentation for the social elite and the newly minted millionaires of the Gilded Age.

Early life[edit]

Hunt was born at Brattleboro, Vermont into the prominent Hunt family. His father, Jonathan Hunt, was a lawyer and U.S. congressman, whose own father, Jonathan Hunt, senior, was lieutenant governor of Vermont.[2] Hunt's mother, Jane Maria Leavitt, was the daughter of Thaddeus Leavitt, Jr., a merchant, and a member of the influential Leavitt family of Suffield, Connecticut.

Richard Morris Hunt was named for Lieut. Richard Morris, an officer in the U.S. Navy, a son of Hunt's aunt,[3][4] whose husband Lewis Richard Morris was a U.S. Congressman from Vermont and the nephew of Gouverneur Morris, author of large parts of the U.S. Constitution.[5] Hunt was the brother of the Boston painter William Morris Hunt, and the photographer and lawyer Leavitt Hunt.

Following the death of his father in Washington, D.C. in 1832 at the age of 44, Hunt's mother moved her family to New Haven, then in 1837 to New York, and then in the spring of 1838 to Boston.[6] There, Hunt enrolled in the Boston Latin School, while his brother William enrolled in Harvard College. However, in the summer of 1842, William left Harvard, transferring to a school in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, while Richard was sent to school in Sandwich, Massachusetts.[7]

European education[edit]

In October 1843, out of concern for William's health, Mrs. Hunt and her five children sailed from New York to Europe, eventually settling in Rome.[8] There, Hunt studied art, but was encouraged by his mother and brother William to pursue architecture.[9] In May 1844, Hunt enrolled in Mr. Briquet's boarding school in Geneva, and the following year, while continuing to board with Mr. Briquet, arranged to study with the Geneva architect Samuel Darier.[10]

In October 1846, Hunt entered the Paris atelier of the architect Hector Lefuel, while studying for the entrance examinations of the École des Beaux-Arts.[11] According to the historian David McCullough, "Hunt was the first American to be admitted to the school of architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts – the finest school of architecture in the world – and the subsequent importance of his influence on the architecture of his own country can hardly be overstated."[12]

In 1853, Hunt's mentor Lefuel was placed in charge of the ambitious project of completing the Louvre, following the death of the project's architect, Louis-Tullius-Joachim Visconti. Lefuel engaged Hunt to help supervise the work, and to help design the Pavillon de la Bibliothèque ("Library Pavilion"), prominently situated opposite the Palais-Royal.[13] Hunt would later regale the sixteen-year-old future architect Louis Sullivan with stories of his work on the Nouveau Louvre in Lefuel's atelier libre.[14]

Career in America[edit]

New York early years[edit]

Hunt spent Christmas 1855 in Paris, after which he returned to the United States. In March 1856, he accepted a position with the architect Thomas Ustick Walter helping Walter with the renovation and expansion of the U.S. Capitol, and the following year moved to New York to establish his own practice. Hunt's first substantial project was the Tenth Street Studio Building, where he rented space, and where in 1858 he founded the first American architectural school, beginning with a small group of students, including George B. Post, William Robert Ware, Henry Van Brunt, and Frank Furness.[15] Ware, who was deeply influenced by Hunt, went on to found America's first two university programs in architecture: at MIT in 1866, and at Columbia in 1881.

Hunt's first New York project, a pair of houses on 37th Street for Thomas P. Rossiter and his father-in-law Dr. Eleazer Parmly, required Hunt to sue Parmly for non-payment of the supervisory portion of his services. The jury awarded Hunt a 2-1/2% commission, at the time the minimum fee typically charged by architects.[16] According to the editors of Engineering Magazine, writing in 1896, the case, "helped to establish a uniform system of charges by percentage."[17]

It was in these early years that Hunt suffered his greatest professional setback, the rejection of his formal, classical proposal for the "Scholars' Gate", the entrance to New York's Central Park at 60th Street and Fifth Avenue.[18] According to Central Park historian Sarah Cedar Miller, the influential Central Park commissioner Andrew Haswell Green supported Hunt's design, but when the park commissioners adopted it, the park's designers, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux (advocates of a more informal design), protested and resigned their positions with the Central Park project. Hunt's plan was ultimately rejected, and Olmsted and Vaux rejoined the project.[19] Nevertheless, one work of Hunt's can be found in the park, albeit a minor one: the rusticated Quincy granite pedestal on which John Quincy Adams Ward's bronze statue The Pilgrim stands, on Pilgrim Hill overlooking the park's East Drive at East 72nd Street.[20][21][22][23]

Hunt's extroverted personality, a factor in his successful career, is well-documented. After meeting Hunt in 1869 the philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in his journal of "one remarkable person new to me, Richard Hunt the architect. His conversation was spirited beyond any I remember, loaded with matter, and expressed with the vigour and fury of a member of the Harvard boat or ball club relating the adventures of one of their matches; inspired, meantime, throughout, with fine theories of the possibilities of art."[24] Hunt was said to be popular with his workmen, and legend has it that during a final walk-through of the William K. Vanderbilt house on Fifth Avenue, Hunt discovered a mysterious tent-like object in one of the ballrooms. Investigating, he found it covering a life-sized statue of himself, dressed in stonecutters' clothes, carved in secret as a tribute by the project's stonecutters. Vanderbilt permitted the statue to be placed on the roof over the entrance to the house. Hunt was said to be pragmatic; his son Richard quoted him as having said, "the first thing you've got to remember is that it's your client's money you're spending. Your goal is to achieve the best results by following their wishes. If they want you to build a house upside down standing on its chimney, it's up to you to do it."[25]

Hunt's professional trajectory gained impetus from his extensive social connections at Newport, Rhode Island, the resort where in 1859 Hunt's brother William bought a house. There in 1860 Hunt met the woman he would marry, Catharine Clinton Howland, the daughter of Samuel S. Howland, a New York shipping merchant, and his wife, Joanna Hone.[26] On April 2, 1861, they married at the Church of the Ascension, on Fifth Avenue at Tenth street,[27] and according to a newspaper reporter, the bride brought a dowry to the marriage of $400,000.[28] Many of Hunt's early wood-frame houses, and many of his later more substantial masonry houses, were built at Newport, some of the latter for the Vanderbilts, the family of railroad tycoons with whom Hunt had a long and rewarding relationship.

New York later years[edit]

Beginning in the 1870s, Hunt acquired more substantial commissions, including New York's Tribune Building (built 1873–75, one of the earliest buildings with an elevator), and the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty (built 1881–86). Hunt devoted much of his practice to institutional work, including the Theological Library and Marquand Chapel at Princeton; the Fogg Museum of Art at Harvard; and the Scroll and Key clubhouse at Yale, all of which except the last have been demolished.

Before Hunt's Lenox Library was completed in 1877 on Fifth Avenue, none of his American works were designed in the Beaux-Arts style with which he is usually associated, of which his entrance façade for the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Fifth Avenue building (completed posthumously in 1902) is perhaps the chief example. Late in life he joined the consortium of architects selected to plan Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, considered to be an exemplar of Beaux-Arts design.[29] Hunt's design for the fair's Administration Building won a gold medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects.

The last surviving New York City buildings entirely by Hunt are the Jackson Square Library and a charity hospital he designed for the Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females, completed in 1883 at Amsterdam Avenue between 103rd and 104th Streets. The red-brick building was renovated in the late 20th century and is now a youth hostel.

The Jackson Square Library, built in 1887 with funds from George Vanderbilt III (Grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt) still exists as well. This particular library — one of the very first purpose-built free and open public library buildings in New York (only the Ottendorfer Library on Second Avenue in the East Village is extant and older) — was also one of the very first libraries to introduce the innovation of open stacks. This allowed the public to actually pick books off the shelves themselves, rather than having to find a card number in a catalog and ask a librarian to retrieve the book for them, which was to this point standard practice, based in part upon fear of theft. The building continued to operate as a library until it was decommissioned in the early 1960s.[30]

Professional advocacy[edit]

Referring to Hunt's efforts to elevate his chosen profession, the architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote in The New York Times that Hunt was "American architecture's first, and in many ways its greatest, statesman."[31] In 1857, Hunt co-founded the New York Society of Architects, which soon became the American Institute of Architects, and from 1888 to 1891 served as the institute's third president. Hunt advocated tirelessly for the improved status of architects, arguing that they should be treated, and paid, as legitimate and respected professionals equivalent to doctors and lawyers. In 1893, Hunt co-founded New York's Municipal Art Society, an outgrowth of the City Beautiful Movement, and served as the society's first president.[32]

Many of Hunt's proteges had successful careers. Among the employees who worked in his firm was the Franco-American architect and École des Beaux-Arts graduate Emmanuel Louis Masqueray who went on to become Chief of Design at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Hunt encouraged artists and craftsmen, frequently employing them to embellish his buildings, most notably the sculptor Karl Bitter who worked on many of Hunt's projects.

Death and legacy[edit]

Hunt died at Newport, Rhode Island in 1895, and was buried at Newport's Common Burying Ground and Island Cemetery. In 1898, the Municipal Art Society commissioned the Richard Morris Hunt Memorial, designed by the architect Bruce Price, with a bust of Hunt and two caryatids (one representing art, the other architecture) sculpted by Daniel Chester French.[33] The memorial was installed in the wall of Central Park along Fifth Avenue near 70th Street, across the avenue from Hunt's Lenox Library, which has since been replaced by the Frick Collection.

Following Hunt's death, his son Richard Howland Hunt continued the practice his father had established,[34] and in 1901 his brother Joseph Howland Hunt joined him to form the successor firm Hunt & Hunt. They completed many of their father's projects, including the 1902 wing of The Met Fifth Avenue. The new wing (for which the father, a museum trustee, had made the initial sketches in 1894) included the Fifth Avenue entrance facade, the entrance hall and grand staircase.[35][36][37]

Selected works[edit]

Houses[edit]

- Thomas P. Rossiter/Eleazer Parmly Houses, New York City (1855–1857).

- J.N.A. Griswold House, Newport, Rhode Island (1863–1864).

- Everett-Dunn House, Tenafly, New Jersey (1867).[38]

- William F. Coles House, The Lodge, Newport, Rhode Island (1869–1870), demolished.

- Martin Brimmer Houses, Boston Massachusetts (1870).

- Richard Baker Jr. House, Westcliff, Newport, Rhode Island (alterations about 1870)

- Richard Morris Hunt House, Hypotenuse, Newport, Rhode Island (alterations about 1870).

- Thomas Gold Appleton House, Newport, Rhode Island (1870–1871), destroyed by fire about 1920.

- Henry Marquand House, Linden Gate, Newport, Rhode Island (1872–1873), destroyed by fire in 1973.

- H.B. Hollins Estate, Meadow Farm, East Islip, New York.

- Jacob Haskell House, Orient Street, Swampscott, Massachusetts (1871–1873).[39]

- Howland Circulating Library, Beacon, New York (1871–72).

- Marshall Field House, Prairie Avenue, Chicago, Illinois (1873–1876), demolished 1955.

- G.P. Wetmore House, Chateau-sur-Mer, Newport, Rhode Island (alterations 1870–1873 and 1876–1880).[40]

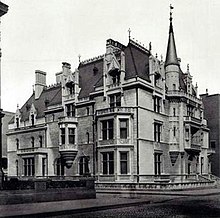

- William K. Vanderbilt House, Petit Chateau, Fifth Avenue, New York City (1878–1882), demolished 1926.[41]

- William Kissam and Alva Vanderbilt House, Idle Hour, Suffolk County, New York (1878–1882), destroyed by fire in 1899.[42]

- Charles W. Shields House, Netherecliffe, Newport, Rhode Island (1881–1883).

- Henry Marquand House, Madison Avenue, New York City (1881–1884), demolished.[43]

- Château de Montméry (built for Theodore Haviland), Ambazac, Haute-Vienne, France (1885).

- James Pinchot House, Grey Towers, Milford, Pennsylvania (1884–1886).

- Ogden Mills House, Fifth Avenue, New York City (1885–1887), demolished.

- William Borden House, Chicago, Illinois (1884–1889), demolished.

- Archibald Rogers Estate, Hyde Park, New York (1886–1889).

- William Kissam Vanderbilt House, Marble House, Newport, Rhode Island (1888–1892).

- J.R. Busk House, Indian Springs, currently known as Wrentham House, Newport, Rhode Island (1889–1892).

- Ogden Goelet House, Ochre Court, Newport, Rhode Island (1888–1893).

- Dorsheimer-Busk House, Newport, Rhode Island (1890–1893).

- Oliver Belmont House, Belcourt, Newport, Rhode Island (1891–1894).

- John Jacob Astor IV House, Fifth Avenue, New York City, (1891–1895), demolished 1926.

- George Washington Vanderbilt House, Biltmore Estate, Asheville, North Carolina (1890–1895), the largest private house in America.

- Cornelius Vanderbilt II house, The Breakers, Newport, Rhode Island (1892–1895).

- Elbridge Gerry House, Fifth Avenue, New York City (1895), demolished 1929.

Public buildings[edit]

- Tenth Street Studio Building, New York City (1857), demolished in 1956.

- Stuyvesant Apartments, 142 East 18th Street, New York City (1869), demolished about 1959.

- Scroll and Key Secret Society, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut (1869).

- East Divinity Hall (Edwards Hall), Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut (1869), demolished.

- Marquand Chapel, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut (1871), demolished.

- Presbyterian Hospital, New York City (1869–1872), demolished.

- Travers Block, Bellevue Avenue, Newport, Rhode Island (1870–1872).

- Howland Cultural Center, Beacon, New York (1872), designed as the Howland Library for Hunt's brother-in-law Joseph Howland.

- First Presbyterian Church, Beacon, New York (1872), partly burned.

- Virginia Hall (and other buildings), Hampton Institute (now Hampton University), Hampton, Virginia (1874).

- New York Tribune Building, New York City (1875), demolished in 1966.

- Lenox Library, Fifth Avenue, New York City (1871–1877), demolished in 1912.

- Lenox Theological Library, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey (1879), demolished about 1956.

- St. Mark's Episcopal Church, Islip, New York (1879–1880).

- Marquand Chapel, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey (1881–1882), destroyed by fire in 1920.

- Association Residence Nursing Home, Amsterdam Avenue, New York City (1881–1883).

- Statue of Liberty (Liberty Enlightening the World) pedestal, Liberty Island (1881–1886).

- Aaron Burr Hall, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey (1891).

- Clark Hall, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio (1891–1892).

- Administration Building, World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, Illinois (1892–1893), demolished.[44]

- Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1892–1895), demolished and replaced in 1925.

- Southern Railway, Biltmore Station, One Biltmore Plaza, Asheville, North Carolina (1896).[45]

- Cathedral of All Souls, Biltmore Village, Asheville, North Carolina (1896).

- The Met Fifth Avenue Main Wing (entrance façade, entrance hall and grand stairway), Fifth Avenue, New York City (completed posthumously in 1902).

Urban design[edit]

- Master plan for Columbia University's Morningside Heights campus, New York City (1892), a losing entry in a three-way competition won by McKim, Mead & White.

Statue pedestal[edit]

- Pedestal to The Pilgrim (statue), Pilgrim Hill, Central Park, New York City (1884)

Gallery[edit]

-

John N. A. Griswold House, Newport, Rhode Island (1861–1863)

-

East Divinity Hall, Yale College (built 1869; demolished)

-

Scroll and Key Tomb, Yale University (1869)

-

Hunt's own house, "Hypotenuse", Newport, Rhode Island (alteration c. 1870)

-

Travers Block, Newport, Rhode Island (1870–71)

-

Marquand Chapel, Yale College (built 1871; demolished)

-

Henry G. Marquand House, Newport, Rhode Island (1872–73)

-

New York Tribune Building, New York City (built 1875; doubled in size in 1905; demolished 1966)

-

Chateau-sur-Mer, Newport, Rhode Island (enlarged and altered in 1870–1873 and 1876–1880)

-

William K. Vanderbilt House, Fifth Avenue, New York City (built 1878–1882; demolished in 1926)

-

Association Residence Nursing Home, Amsterdam Avenue, New York City (built 1883)

-

Henry G. Marquand House, Madison Avenue, New York City (built 1884; demolished)

-

Statue of Liberty (Liberty Enlightening the World) pedestal (built 1881–1886)

-

Jackson Square Library, New York City (1887)

-

Marble House, Newport, Rhode Island (built 1888–1892)

-

Ochre Court, Newport, Rhode Island (built 1888–1893)

-

Biltmore Estate, America's largest private house, designed for George Washington Vanderbilt II (built 1890–1895)

-

Vanderbilt Mausoleum, Staten Island, New York (built 1885–1886)

-

Administration Building, World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago (completed 1893, demolished)

-

The Elbridge Gerry House, Fifth Avenue, New York City (completed in 1895; demolished)

-

The Fogg Museum of Art, Harvard University (completed in 1895; demolished in 1925)

-

Entrance wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City (completed posthumously in 1902)

Awards and honors[edit]

- Honorary Doctorate, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts (first architect to receive the honor)[46]

- Royal Gold Medal, Royal Institute of British Architects, 1893 (first American architect to be so honored)

- Honorary member, Académie française

- Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, France[47]

See also[edit]

- Thaddeus Leavitt

- Jarvis Hunt

- Jonathan Hunt (Vermont Representative)

- Jonathan Hunt (Vermont Lieutenant Governor)

- Leavitt Hunt

- William Morris Hunt

- Richard Sharp Smith

References[edit]

Notes

- ^ "The Harvard Graduates' Magazine". Harvard Graduates' Magazine Association. March 30, 1893 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dwight, Benjamin Woodbridge (March 30, 1874). The History of the Descendants of John Dwight, of Dedham, Mass. J. F. Trow & son, printers and bookbinders. ISBN 9781981482658 – via Google Books.

- ^ Catharine Howland Hunt, Unpublished Biography of Richard Morris Hunt (1896–1906), page 1.

- ^ Lewis Richard Morris was married to Ellen Hunt, a sister of Richard Morris Hunt's father. See General Lewis R. Morris House, Springfield, Vt., National Register, Connecticut River Joint Commissions, crjc.org

- ^ Obituary of Richard Morris Hunt, The New York Times, August 1, 1895

- ^ Catharine Howland Hunt, Unpublished Biography of Richard Morris Hunt (1896–1906), page 16.

- ^ Catharine Howland Hunt, Unpublished Biography of Richard Morris Hunt (1896–1906), pages 19,20.

- ^ Catharine Howland Hunt, Unpublished Biography of Richard Morris Hunt (1896–1906), pages 19,20.

- ^ Puritan Boston & Quaker Philadelphia, Edward Digby Baltzell, Published by Transaction Publishers, 1996 ISBN 1-56000-830-X

- ^ Catharine Howland Hunt, Unpublished Biography of Richard Morris Hunt (1896–1906), pages 23,24.

- ^ Catharine Howland Hunt, Unpublished Biography of Richard Morris Hunt (1896–1906), pages 25.

- ^ McCullough, David (2011). The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781416576891.

- ^ Dwight, Benjamin Woodbridge (March 30, 1874). The History of the Descendants of John Dwight, of Dedham, Mass. J. F. Trow & son, printers and bookbinders. ISBN 9781981482658 – via Google Books.

- ^ Morrison, Hugh (March 30, 2018). Louis Sullivan, Prophet of Modern Architecture. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393730234 – via Google Books.

- ^ Catharine Howland Hunt, Unpublished Biography of Richard Morris Hunt (1896–1906), pages 99-110.

- ^ Catharine Howland Hunt, Unpublished Biography of Richard Morris Hunt (1896–1906), page 103.

- ^ Engineering Magazine, Vol. 10, The Engineering Magazine Co., New York, 1896

- ^ SOUZA, J. DA C. G. DE.; FRANCO, J. L. DE A. «Frederick Law Olmsted: Landscape Architecture and North American National Parks». Topoi, (Rio J.), Rio de Janeiro. v.21 (n.45): p. 754-774, sept./dec. 2020.

- ^ Miller, Sara Cedar: Central Park, An American Masterpiece p. 57. Harry N. Abrams, Inc, 2003 ISBN 0-8109-3946-0.

- ^ "Pilgrim : NYC Parks". Central Park Monuments. June 26, 1939. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ "Pilgrim Hill". www.centralpark.com. April 3, 2019. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ "Pilgrim Hill". Central Park Conservancy. July 28, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ Carroll, R.; Berenson, R.J. (2008). The Complete Illustrated Map and Guidebook to Central Park. Sterling Publishing Company, Incorporated. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-4027-5833-1. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ Ralph Waldo Emerson (1914). Edward Waldo Emerson and Waldo Emerson Forbes (ed.). Journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1864–1876. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 280.

- ^ van Pelt, A Monograph of the William K. Vanderbilt House, 10, cited in Vanderbilt, Arthur T. Fortune's Children. William Morrow and Co., 1989, 89.

- ^ Catharine Howland Hunt, Unpublished Biography of Richard Morris Hunt (1896–1906), page 127.

- ^ Catharine Howland Hunt, Unpublished Biography of Richard Morris Hunt (1896–1906), page 131.

- ^ Hartford Courant, April 10, 1861, page 2.

- ^ Moseley, D.S. (1893). Picturesque Chicago and Guide to the World's Fair. p. 192. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ "Jackson Square Library: An Exquisite Building, and once a church of 'Exquisite Panic'". Village Preservation. July 6, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (May 22, 1986). "ARCHITECTURE: TWO RICHARD MORRIS HUNT SHOWS". The New York Times.

- ^ "To Make the City Beautiful," The New York Times, April 20, 1893, page 6.

- ^ "The Municipal Art Society of New York". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 11, 2007. History of the Municipal Art Society (official site)

- ^ Anonymous (October 1, 2009). Prominent Families of New York. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 9781115372305 – via Google Books.

- ^ "New Art Museum Wing," The New York Times, December 22, 1902, page 6.

- ^ MacKay, Robert B.; Baker, Anthony K.; Traynor, Carol A. (March 30, 1997). Long Island Country Houses and Their Architects, 1860-1940. Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities in association with, W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393038569 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Finding aid for the Henry Gurdon Marquand Papers, 1852-1903" (PDF). libmma.org.

- ^ "Everett – Dunn House Historical Marker". hmdb.org.

- ^ Thompson, Waldo (1885). Swampscott: Historical Sketches of the Town. p. 205.

- ^ llc, CC inspire. "Chateau-sur-Mer - Architecture & Design". www.newportmansions.org.

- ^ Craven, Wayne (2009). Gilded Mansions: Grand Architecture and High Society. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 111–126. ISBN 978-0-393067-54-5.

- ^ "VANDERBILT VILLA BURNED; Flames Cut Short W.K. Vanderbilt, Jr.'s, Honeymoon at Idle Hour. NARROW ESCAPE WITH BRIDE Flames Started While Household Slept -- Incendiary, Mr. Vanderbilt Says -- Bad Flue, Perhaps". The New York Times. April 12, 1899. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Henry Gurdon Marquand joined Charles McKim as a pallbearer at Hunt's funeral.

- ^ Gold medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects.

- ^ Potter, Janet Greenstein (1996). Great American Railroad Stations. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 266. ISBN 978-0471143895.

- ^ "The Harvard Graduates' Magazine". Harvard Graduates' Magazine Association. March 30, 1893 – via Google Books.

- ^ Rybczynski, Witold (March 30, 2018). The Look of Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195156331 – via Google Books.

Bibliography

- Baker, Paul, Richard Morris Hunt, MIT Press, 1980

- Durante, Dianne, Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan: A Historical Guide (New York University Press, 2007): brief summary of Hunt's career and description of Daniel Chester French's Hunt memorial in Central Park, New York.

- Great Buildings Online

- Kvaran. Einar Einarsson, Architectural Sculpture of America

- Stein, Susan Editor, The Architecture of Richard Morris Hunt, University of Chicago Press, 1986

Further reading

- Exploration, Vision & Influence: The Art World of Brattleboro's Hunt Family, Catalogue, Museum Exhibition, The Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont, June 23 – December 31, 2005, Paul R. Baker, Sally Webster, David Hanlon, and Stephen Perkins

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Richard Morris Hunt at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Richard Morris Hunt at Wikimedia Commons

- Richard Morris Hunt at Find a Grave

- Death of Richard Morris Hunt, One of the Foremost Architects of the United States, The New York Times, August 1, 1895

- Additional obituary, Richard Morris Hunt, The New York Times, August 1, 1895

- nyc-architecture.com

- Richard Morris Hunt collection, The Octagon Museum, The Museum of The American Architectural Foundation, Washington, D.C.