| Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | POTS |

| |

| Acrocyanosis in a male Norwegian POTS patient | |

| Specialty | Cardiology, neurology |

| Symptoms | More often with standing: lightheadedness, trouble thinking, tachycardia, weakness,[1] palpitations, heat intolerance, acrocyanosis |

| Usual onset | Most common (modal) age of onset is 14 years[2] |

| Types | Neuropathic POTS, Hyperadrenergic POTS, Secondary POTS. |

| Causes | Antibodies against the Alpha 1 adrenergic receptor and muscarinic acetylcholine M4 receptor[3][4][5] |

| Risk factors | Family history,[1] Ehlers Danlos Syndrome |

| Diagnostic method | An increase in heart rate by 30 beats/min with standing[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Dehydration, heart problems, adrenal insufficiency, epilepsy, Parkinson's disease,[6] anemia |

| Treatment | Avoiding factors that bring on symptoms, increasing dietary salt and water, compression stockings, exercise, medications[1] |

| Medication | Off label Medications: Beta blockers, Ivabradine, midodrine, and fludrocortisone.[1] |

| Prognosis | c. 90% improve with treatment,[7] 25% of patients unable to work[8] |

| Frequency | ~ 1,000,000 ~ 3,000,000 (US)[9] |

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a condition characterized by an abnormally large increase in heart rate upon sitting up or standing.[1] POTS is a disorder of the autonomic nervous system that can lead the individual to experience a variety of symptoms.[10] Symptoms may include lightheadedness, brain fog, blurred vision, weakness, fatigue, headaches, heart palpitations, exercise intolerance, nausea, diminished concentration, tremulousness (shaking), syncope (fainting), coldness or pain in the extremities, chest pain and shortness of breath.[1][11][12] Other conditions associated with POTS include migraine headaches, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, asthma, autoimmune disease, vasovagal syncope and mast cell activation syndrome.[10][13] POTS symptoms may be treated with lifestyle changes such as increasing fluid, electrolyte, and salt intake, wearing compression stockings, gentler and slow postural changes, avoiding prolonged bedrest, medication, and physical therapy.

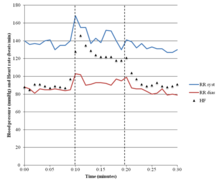

The causes of POTS are varied.[14] POTS may develop after a viral infection, surgery, trauma, or pregnancy.[7] It has been shown to emerge in previously healthy patients after COVID-19,[15][16] or in rare cases after COVID-19 vaccination.[17] POTS is more common among people who got infected with SARS-CoV-2 than among those who got vaccinated against COVID-19.[18] Risk factors include a family history of the condition.[1] POTS in adults is characterized by a heart rate increase of 30 beats per minute within ten minutes of standing up, accompanied by other symptoms.[1] This increased heart rate should occur in the absence of orthostatic hypotension (>20 mm Hg drop in systolic blood pressure)[19] to be considered POTS. A spinal fluid leak (called spontaneous intracranial hypotension) may have the same signs and symptoms as POTS and should be excluded.[20] Prolonged bedrest may lead to multiple symptoms, including blood volume loss and postural tachycardia.[21] Other conditions which can cause similar symptoms, such as dehydration, orthostatic hypotension, heart problems, adrenal insufficiency, epilepsy, and Parkinson's disease, must not be present.[6]

Treatment may include avoiding factors that bring on symptoms, increasing dietary salt and water, small and frequent meals,[22] avoidance of immobilization,[22] wearing compression stockings, and taking medications.[23][24][1][25] Medications used may include beta blockers,[26] pyridostigmine,[27] midodrine[28] or fludrocortisone.[1] More than 50% of patients whose condition was triggered by a viral infection get better within five years.[7] About 80% of patients have symptomatic improvement with treatment, while 25 percent of patients are so disabled they are unable to work.[8][7] A retrospective study on patients with adolescent-onset has shown that five years after diagnosis, 19% of patients had a full resolution of symptoms.[29]

It is estimated that 1–3 million people in the United States have POTS.[30] The average age for POTS onset is 20 years, and it occurs about five times more frequently in females than in males.[1]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

POTS is a complex and multifaceted clinical disorder, the etiology and management of which remain incompletely understood. This syndrome is typified by a diverse array of nonspecific symptoms, making it a challenging condition to describe.[31]

Individuals living with POTS experience a diminished quality of life compared to healthy individuals, due to disruptions in various domains such as standing, playing sports, symptom anxiety, and impacts on school, work, or spiritual (religious) domains—these disruptions affect their daily life and overall well-being.[32]

In adults, the primary manifestation is an increase in heart rate of more than 30 beats per minute within ten minutes of standing up.[1][33] The resulting heart rate is typically more than 120 beats per minute.[1] For people between ages 12 and 19, the minimum increase for a POTS diagnosis is 40 beats per minute.[34] POTS is often accompanied by common features of orthostatic intolerance—in which symptoms that develop while upright are relieved by reclining.[33] These orthostatic symptoms include palpitations, light-headedness, chest discomfort, shortness of breath,[33] nausea, weakness or "heaviness" in the lower legs, blurred vision, and cognitive difficulties.[1] Symptoms may be exacerbated with prolonged sitting, prolonged standing, alcohol, heat, exercise, or eating a large meal.[citation needed]

Up to one-third of POTS patients experience fainting for many reasons, including but not limited to standing, physical exertion, or heat exposure.[1] POTS patients may also experience orthostatic headaches.[35] Some POTS patients may develop blood pooling in the extremities, characterized by a reddish-purple color of the legs and/or hands upon standing.[36][37][38][39] 48% of people with POTS report chronic fatigue and 32% report sleep disturbances.[40][41][42][43] Other POTS patients only exhibit the cardinal symptom of orthostatic tachycardia.[38] Additional signs and symptoms are varied, and may include excessive sweating, lack of sweating, heat intolerance, digestive issues such as nausea, indigestion, constipation or diarrhea, post-exertional malaise, coat-hanger pain, brain fog, and syncope or presyncope.[44]

Whereas POTS is primarily characterized by its profound impact on the autonomic and cardiovascular systems, it can lead to substantial functional impairment. This impairment, often manifesting as symptoms such as fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and sleep disturbances, can significantly diminish the patient's quality of life.[32]

Brain fog[edit]

One of the most disabling and prevalent symptoms in POTS is "brain fog",[11] a term used by patients to describe the cognitive difficulties they experience. In one survey of 138 POTS patients, brain fog was defined as "forgetful" (91%), "difficulty thinking" (89%), and "difficulty focusing" (88%). Other common descriptions were "difficulty processing what others say" (80%), "confusion" (71%), "getting lost" (64%), and "thoughts moving too quickly" (40%).[12] The same survey described the most common triggers of brain fog to be fatigue (91%), lack of sleep (90%), prolonged standing (87%), and dehydration (86%).[citation needed]

Neuropsychological testing has shown that a POTS patient has reduced attention (Ruff 2&7 speed and WAIS-III digits forward), short-term memory (WAIS-III digits back), cognitive processing speed (Symbol digits modalities test), and executive function (Stroop word color and trails B).[45][46][47]

A potential cause for brain fog is a decrease in cerebral blood flow (CBF), especially in upright position.[48][49][50]

There may be a loss of neurovascular coupling and reduced functional hyperemia in response to cognitive challenge under orthostatic stress – perhaps related to a loss of autoregulatory buffering of beat-by-beat fluctuations in arterial blood flow.[51]

Causes[edit]

The pathophysiology of POTS is not attributable to a single cause or unified hypothesisem—it is the result of multiple interacting mechanisms, each contributing to the overall clinical presentation; the mechanisms may include autonomic dysfunction, hypovolemia, deconditioning, hyperadrenergic states, etc.[31]

The symptoms of POTS can be caused by several distinct pathophysiological mechanisms.[33] These mechanisms are poorly understood,[34] and can overlap, with many patients showing features of multiple POTS types.[33] Many people with POTS exhibit low blood volume (hypovolemia), which can decrease the rate of blood flow to the heart.[33] To compensate for low blood volume, the heart increases its cardiac output by beating faster (reflex tachycardia),[52] leading to the symptoms of presyncope.

In the 30% to 60% of cases classified as hyperadrenergic POTS, norepinephrine levels are elevated on standing,[1] often due to hypovolemia or partial autonomic neuropathy.[33] A smaller minority of people with POTS have (typically very high) standing norepinephrine levels that are elevated even in the absence of hypovolemia and autonomic neuropathy; this is classified as central hyperadrenergic POTS.[33][39] The high norepinephrine levels contribute to symptoms of tachycardia.[33] Another subtype, neuropathic POTS, is associated with denervation of sympathetic nerves in the lower limbs.[33] In this subtype, it is thought that impaired constriction of the blood vessels causes blood to pool in the veins of the lower limbs.[1] Heart rate increases to compensate for this blood pooling.[53]

In up to 50% of cases, there was an onset of symptoms following a viral illness.[54] It may also be linked to physical trauma, concussion, pregnancy, surgery or psychosocial stress.[55][22][38] It is believed that these events could act as a trigger for an autoimmune response that result in POTS.[56] It has been shown to emerge in previously healthy patients after COVID-19,[57][15][16] or after COVID-19 vaccination.[17] A 2023 review found that the chances of being diagnosed with POTS within 90 days after mRNA vaccination were 1.33 times higher compared to 90 days before vaccination, still, the results are inconclusive due to a small sample size; only 12 cases of newly diagnosed POTS after mRNA vaccination were reported, all these 12 patients having autoimmune antibodies. However, the risk of POTS-related diagnoses was 5.35 times higher after getting infected with SARS-CoV-2 compared to after mRNA vaccination.[58] Possible mechanisms for COVID-induced POTS are hypovolemia, autoimmunity/inflammation from antibody production against autonomic nerve fibers, and direct toxic effects of COVID-19, or secondary sympathetic nervous system stimulation.[57]

POTS is more common in females than males. POTS also has been linked to patients with a history of autoimmune diseases,[55] Long Covid,[59] irritable bowel syndrome, anemia, hyperthyroidism, fibromyalgia, diabetes, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and cancer. Genetics likely plays a role, with one study finding that one in eight POTS patients reported a history of orthostatic intolerance in their family.[52]

Autoimmunity[edit]

There is an increasing number of studies indicating that POTS is an autoimmune disease.[55][5][60][3][61][62] A high number of patients has elevated levels of autoantibodies against the adrenergic alpha 1 receptor and against the muscarinic acetylcholine M4 receptor.[63][4][64]

Elevations of autoantibodies targeting adrenergic α1 receptor has been associated with symptoms severity in patients with POTS.[63]

More recently, autoantibodies against other targets have been identified in small cohorts of POTS patients.[65] Signs of innate immune system activation with elaboration of pro-inflammatory cytokines has also been reported in a cohort of POTS patients.[66]

Secondary POTS[edit]

If POTS is caused by another condition, it may be classified as secondary POTS.[7] Chronic diabetes mellitus is one common cause.[7] POTS can also be secondary to gastrointestinal disorders that are associated with low fluid intake due to nausea or fluid loss through diarrhea, leading to hypovolemia.[1] Systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases have also been linked to POTS.[55]

There is a subset of patients who present with both POTS and mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), and it is not yet clear whether MCAS is a secondary cause of POTS or simply comorbid, however, treating MCAS for these patients can significantly improve POTS symptoms.[23]

POTS can also co-occur in all types of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (EDS),[38] a hereditary connective tissue disorder marked by loose hypermobile joints prone to subluxations and dislocations, skin that exhibits moderate or greater laxity, easy bruising, and many other symptoms. A trifecta of POTS, EDS, and mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) is becoming increasingly more common, with a genetic marker common among all three conditions.[67][68][69][70] POTS is also often accompanied by vasovagal syncope, with a 25% overlap being reported.[71] There are some overlaps between POTS and chronic fatigue syndrome, with evidence of POTS in 10–20% of CFS cases.[72][71] Fatigue and reduced exercise tolerance are prominent symptoms of both conditions, and dysautonomia may underlie both conditions.[71]

POTS can sometimes be a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with cancer.[73]

There are case reports of people developing POTS and other forms of dysautonomia post-COVID.[16][74][75][76] There is no good large-scale empirical evidence yet to prove a connection, so for now the evidence is preliminary.[77]

Diagnosis[edit]

POTS is a complex disorder with a multifactorial etiology, and the diagnostics of POTS is challenging.[31]

POTS is most commonly diagnosed by a cardiologist (41%), cardiac electrophysiologist (15%), or neurologist (19%).[2] The average number of physicians seen before receiving diagnosis is seven, and the average delay before diagnosis is 4.7 years.[2]

Diagnostic criteria[edit]

A POTS diagnosis requires the following characteristics:[10]

- For patients age 20 or older, a sustained increase in heart rate ≥30 bpm within ten minutes of upright posture (tilt table test or standing) from a supine position.

- For patients age 12–19, heart rate increase must be >40 bpm.

- Associated with frequent symptoms of lightheadedness, palpitations, tremulousness, generalized weakness, blurred vision, or fatigue that are worse with upright posture and that improve with recumbence.

- An absence of orthostatic hypotension (i.e. no sustained systolic blood pressure drop of 20 mmHg or more).

- Chronic symptoms that have lasted for longer than three months.

- In the absence of other disorders, medications, or functional states that are known to predispose to orthostatic tachycardia.

Alternative tests to the tilt table test are also used, such as the NASA Lean Test[78] and the adapted Autonomic Profile (aAP)[79] which require less equipment to complete.

Orthostatic intolerance[edit]

An increase in heart rate upon moving to an upright posture is known as orthostatic (upright) tachycardia (fast heart rate). It occurs without any coinciding drop in blood pressure, as that would indicate orthostatic hypotension.[33] Certain medications to treat POTS may cause orthostatic hypotension. It is accompanied by other features of orthostatic intolerance—symptoms that develop in an upright position and are relieved by reclining.[33] These orthostatic symptoms include palpitations, light-headedness, chest discomfort, shortness of breath,[33] nausea, weakness or "heaviness" in the lower legs, blurred vision, and cognitive difficulties.[1]

Differential diagnoses[edit]

A variety of autonomic tests are employed to exclude autonomic disorders that could underlie symptoms, while endocrine testing is used to exclude hyperthyroidism and rarer endocrine conditions.[38] Electrocardiography is normally performed on all patients to exclude other possible causes of tachycardia.[1][38] In cases where a particular associated condition or complicating factor are suspected, other non-autonomic tests may be used: echocardiography to exclude mitral valve prolapse, and thermal threshold tests for small-fiber neuropathy.[38]

Testing the cardiovascular response to prolonged head-up tilting, exercise, eating, and heat stress may help determine the best strategy for managing symptoms.[38] POTS has also been divided into several types (see § Causes), which may benefit from distinct treatments.[80] People with neuropathic POTS show a loss of sweating in the feet during sweat tests, as well as impaired norepinephrine release in the leg,[81] but not arm.[1][80][82] This is believed to reflect peripheral sympathetic denervation in the lower limbs.[81][83][1] People with hyperadrenergic POTS show a marked increase of blood pressure and norepinephrine levels when standing, and are more likely to have from prominent palpitations, anxiety, and tachycardia.[84][85][54][80]

People with POTS can be misdiagnosed with inappropriate sinus tachycardia (IST) as they present similarly. One distinguishing feature is those with POTS rarely exhibit >100 bpm while in a supine position, while patients with IST often have a resting heart rate >100 bpm. Additionally patients with POTS display a more pronounced change in heart rate in response to postural change.[7]

Treatment[edit]

Despite numerous therapeutic interventions proposed for the management of POTS, none have received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for this indication, and no effective treatment strategies have been identified that would have been confirmed by large clinical trials.[31]

POTS treatment involves using multiple methods in combination to counteract cardiovascular dysfunction, address symptoms, and simultaneously address any associated disorders.[38] For most patients, water intake should be increased, especially after waking, in order to expand blood volume (reducing hypovolemia).[38] Eight to ten cups of water daily are recommended.[23] Increasing salt intake, by adding salt to food, taking salt tablets, or drinking sports drinks and other electrolyte solutions is an effective way to raise blood pressure by helping the body retain water. Different physicians recommend different amounts of sodium to their patients.[86] Combining these techniques with gradual physical training enhances their effect.[38] In some cases, when increasing oral fluids and salt intake is not enough, intravenous saline or the drug desmopressin is used to help increase fluid retention.[38][39]

Large meals worsen symptoms for some people. These people may benefit from eating small meals frequently throughout the day instead.[38] Alcohol and food high in carbohydrates can also exacerbate symptoms of orthostatic hypotension.[34] Excessive consumption of caffeine beverages should be avoided, because they can promote urine production (leading to fluid loss) and consequently hypovolemia.[38] Exposure to extreme heat may also aggravate symptoms.[23]

Prolonged physical inactivity can worsen the symptoms of POTS.[38] Techniques that increase a person's capacity for exercise, such as endurance training or graded exercise therapy, can relieve symptoms for some patients.[38] Aerobic exercise performed for 20 minutes a day, three times a week, is sometimes recommended for patients who can tolerate it.[86] Exercise may have the immediate effect of worsening tachycardia, especially after a meal or on a hot day.[38] In these cases, it may be easier to exercise in a semi-reclined position, such as riding a recumbent bicycle, rowing, or swimming.[38]

When changing to an upright posture, finishing a meal, or concluding exercise, a sustained hand grip can briefly raise the blood pressure, possibly reducing symptoms.[38] Compression garments can also be of benefit by constricting blood pressures with external body pressure.[38]

Aggravating factors include exertion (81%), continued standing (80%), heat (79%), and after meals (42%).[87]

Medication[edit]

If nonpharmacological methods are ineffective, medication may be necessary.[38] Medications used may include beta blockers, pyridostigmine, midodrine,[88] or fludrocortisone.[89][1] As of 2013, no medication has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat POTS, but a variety are used off-label.[23] Their efficacy has not yet been examined in long-term randomized controlled trials.[23]

Fludrocortisone may be used to enhance sodium retention and blood volume, which may be beneficial not only by augmenting sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction, but also because a large subset of POTS patients appear to have low absolute blood volume.[90] However, fludrocortisone may cause hypokalemia.[91]

While people with POTS typically have normal or even elevated arterial blood pressure, the neuropathic form of POTS is presumed to constitute a selective sympathetic venous denervation.[90] In these patients the selective Alpha-1 adrenergic receptor agonist midodrine may increase venous return, enhance stroke volume, and improve symptoms.[90] Midodrine should only be taken during the daylight hours as it may promote supine hypertension.[90]

Sinus node blocker Ivabradine can successfully restrain heart rate in POTS without affecting blood pressure, demonstrated in approximately 60% of people with POTS treated in an open-label trial of ivabradine experienced symptom improvement.[92][93][90]

Pyridostigmine has been reported to restrain heart rate and improve chronic symptoms in approximately half of people. However, it may cause GI side effects that limit its use in around 20% of its patient population.[94][23]

The selective alpha-1 agonist phenylephrine has been used successfully to enhance venous return and stroke volume in some people with POTS.[95] However, this medication may be hampered by poor oral bioavailability.[96]

| POTS subtypes | Therapeutic action | Goal | Drug(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropathic POTS | Alpha-1 adrenergic receptor agonist | Constrict the peripheral blood vessels aiding venous return. | Midodrine[28][97][98][99] |

| Splanchnic–mesenteric vasoconstriction | Splanchnic vasoconstriction | Octreotide[100][101] | |

| Hypovolemic POTS | Synthetic mineralocorticoid | Forces the body to retain salt. Increase blood volume | Fludrocortisone (Florinef)[102][103] |

| Vasopressin receptor agonist | Helps retain water, Increase blood volume | Desmopressin (DDAVP) [104] | |

| Hyperadrenergic POTS | Beta-blockers (non-selective) | Decrease sympathetic tone and heart rate. | Propranolol (Inderal)[105][106][107] |

| Beta-blockers (selective) | Metoprolol (Toprol),[97][108] Bisoprolol[109][102] | ||

| Selective sinus node blockade | Directly reducing tachycardia. | Ivabradine[92][93][110][111][112] | |

| Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist | Decreases blood pressure and sympathetic nerve traffic. | Clonidine,[23] Methyldopa[23] | |

| Anticholinesterase inhibitors | Splanchnic vasoconstriction. Increase blood pressure. | Pyridostigmine[27][113][114] | |

| Other (refractory POTS) | Psychostimulant | Improve cognitive symptoms (brain fog) | Modafinil[115][116] |

| Central nervous system stimulant | Tighten blood vessels. Increases alertness and improves brain fog. | Methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta)[117] | |

| Direct and indirect α1-adrenoreceptor agonist. | Increased blood flows | Ephedrine and Pseudoephedrine[118] | |

| Norepinephrine precursor | Improve blood vessel contraction | Droxidopa (Northera)[118][119] | |

| Alpha-2 adrenergic antagonist | Increase blood pressure | Yohimbine[120] |

Prognosis[edit]

POTS has a favorable prognosis when managed appropriately.[38] Symptoms improve within five years of diagnosis for many patients, and 60% return to their original level of functioning.[38] Approximately 90% of people with POTS respond to a combination of pharmacological and physical treatments.[7] Those who develop POTS in their early to mid teens will likely respond well to a combination of physical methods as well as pharmacotherapy.[121] Outcomes are more guarded for adults newly diagnosed with POTS.[52] Some people do not recover, and a few even worsen with time.[7] The hyperadrenergic type of POTS typically requires continuous therapy.[7] If POTS is caused by another condition, outcomes depend on the prognosis of the underlying disorder.[7]

Epidemiology[edit]

The prevalence of POTS is unknown.[38] One study estimated a minimal rate of 170 POTS cases per 100,000 individuals, but the true prevalence is likely higher due to underdiagnosis.[38] Another study estimated that there are at least 500,000 cases in the United States.[6] POTS is more common in women than men, with a female-to-male ratio of 4:1.[80][122] Most people with POTS are aged between 20 and 40, with an average onset of 21.[2][80] Diagnoses of POTS beyond age 40 are rare, perhaps because symptoms improve with age.[38]

As recently stated,[123] up to one-third of POTS patients also present with Vasovagal Syncope (VVS). This ratio is probably higher if pre-Syncope patients, patients that report the symptoms of Syncope without overt fainting, were included. Given the difficulty with current autonomic measurements in quantitatively isolating and differentiating Parasympathetic (Vagal) activity from Sympathetic activity without assumption or approximation, the current direction of research and clinical assessment is understandable: perpetuating uncertainty regarding underlying cause, prescribing beta-blockers and proper daily hydration as the only therapy, not addressing the orthostatic dysfunction as the underlying cause, and recommending acceptance and associated lifestyle changes to cope.

Direct measures of Parasympathetic (Vagal) activity obviates the uncertainty and lack of true relief of POTS as well as VVS. For example, the hypothesis that POTS is an auto-immune disorder may be an indication that a significant number of POTS cases are indeed co-morbid with VVS. Remember the Parasympathetic Nervous System is the memory for, and controls and coordinates, the immune system. If Parasympathetic (Vagal) over-, or prolonged-, activation is chronic then portions of the immune system may remain active beyond the limits of the infection. Given that portions of the immune system are not of self, these portions remain active and continue to “feed.” Once the only source of “feed” is self, the immune system begins to attack the host. This is the definition of autoimmune. This is a counter-hypothesis that may provide a simpler explanation with a more immediate plan for therapy and relief. For it may be that relieving the Vagal over-activation, will retires the self-attacking portion of the immune system, thereby relieving the autoimmunity.

Another example may be “Hyperadrenergic POTS.” A counter hypothesis and perhaps a simpler explanation that leads to more direct therapy and improved outcomes is again the fact that POTS and VVS may be co-morbid. It is well known that Parasympathetic (Vagal) over-activation may cause secondary Sympathetic over-activation. Without direct Parasympathetic (Vagal) measures, the resulting assumption is that the secondary Sympathetic over-activation (the definition of “hyperadrenergic”) is actually the primary autonomic dysfunction. Simply treating the (secondary) Sympathetic over-activation may be just treating a symptom in these cases, which may work for a while but then the body compensates and more medication is needed or the patient become unresponsive and the permanent degraded lifestyles are considered the only option. Again, this is unfortunate. Given that cases of POTS with VVS involves different portions of the nervous system (Parasympathetic and Sympathetic), and that both branches may be treated simultaneously, albeit differently, true relief of both conditions, as needed, is quite possible, and the cases of these newer hypothesized causes may be relieved with current, less expensive, and shorter-term therapy modalities.

Co-morbidities[edit]

Conditions that are commonly reported with POTS include:[10][13]

- Migraine headaches (40%)

- Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (18–25%)[124]

- Asthma (20%)

- Autoimmune disease (16%)

- Vasovagal syncope (13%)

- Mast cell activation disorder (9%)

Research directions[edit]

A key area for further exploration of POTS management is the autonomic nervous system and its response to the orthostatic challenge. The autonomic nervous system plays a crucial role in maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis during changes in posture. A deeper understanding of its function and the alterations that occur in POTS could provide valuable insights into potential therapeutic targets and the mechanisms of POTS treatment.[31]

History[edit]

In 1871, physician Jacob Mendes Da Costa described a condition that resembled the modern concept of POTS. He named it irritable heart syndrome.[38] Cardiologist Thomas Lewis expanded on the description, coining the term soldier's heart because it was often found among military personnel.[38] The condition came to be known as Da Costa's syndrome,[38] which is now recognized as several distinct disorders, including POTS.[citation needed]

Postural tachycardia syndrome was coined in 1982 in a description of a patient who had postural tachycardia, but not orthostatic hypotension.[38] Ronald Schondorf and Phillip A. Low of the Mayo Clinic first used the name postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, POTS, in 1993.[38][125]

Notable cases[edit]

British politician Nicola Blackwood revealed in March 2015 that she had been diagnosed with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome in 2013 and that she had later been diagnosed with POTS.[126] She was appointed Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Life Science by Prime Minister Theresa May in 2019 and given a life peerage that enabled her to take a seat in Parliament. As a junior minister, it is her responsibility to answer questions in parliament on the subjects of Health and departmental business. When answering these questions, it is customary for ministers to sit when listening to the question and then to rise to give an answer from the despatch box, thus standing up and sitting down numerous times in quick succession throughout a series of questions. On 17 June 2019, she fainted during one of these questioning sessions after standing up from a sitting position four times in the space of twelve minutes,[127] and it was suggested that her POTS was a factor in her fainting. Asked about the incident, she stated: "I was frustrated and embarrassed my body gave up on me at work ... But I am grateful it gives me a chance to shine a light on a condition many others are also living with."[128]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Benarroch EE (December 2012). "Postural tachycardia syndrome: a heterogeneous and multifactorial disorder". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 87 (12): 1214–1225. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.013. PMC 3547546. PMID 23122672.

- ^ a b c d Shaw BH, Stiles LE, Bourne K, Green EA, Shibao CA, Okamoto LE, et al. (October 2019). "The face of postural tachycardia syndrome - insights from a large cross-sectional online community-based survey". Journal of Internal Medicine. 286 (4): 438–448. doi:10.1111/joim.12895. PMC 6790699. PMID 30861229.

- ^ a b Miller AJ, Doherty TA (October 2019). "Hop to It: The First Animal Model of Autoimmune Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome". Journal of the American Heart Association. 8 (19): e014084. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.014084. PMC 6806054. PMID 31547756.

- ^ a b Gunning WT, Kvale H, Kramer PM, Karabin BL, Grubb BP (September 2019). "Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome Is Associated With Elevated G-Protein Coupled Receptor Autoantibodies". Journal of the American Heart Association. 8 (18): e013602. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.013602. PMC 6818019. PMID 31495251.

- ^ a b Fedorowski A, Li H, Yu X, Koelsch KA, Harris VM, Liles C, et al. (July 2017). "Antiadrenergic autoimmunity in postural tachycardia syndrome". Europace. 19 (7): 1211–1219. doi:10.1093/europace/euw154. PMC 5834103. PMID 27702852.

- ^ a b c Bogle JM, Goodman BP, Barrs DM (May 2017). "Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome for the otolaryngologist". The Laryngoscope. 127 (5): 1195–1198. doi:10.1002/lary.26269. PMID 27578452. S2CID 24233032.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Grubb BP (May 2008). "Postural tachycardia syndrome". Circulation. 117 (21): 2814–2817. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.761643. PMID 18506020.

- ^ a b Busmer L (2011). "Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: Lorna Busmer explains how nurses in primary care can recognise the symptoms of this poorly understood condition and offer effective treatment". Primary Health Care. 21 (9): 16–20. doi:10.7748/phc2011.11.21.9.16.c8794.

- ^ "Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS)". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. December 21, 2022. Archived from the original on November 13, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, Grubb BP, Fedorowski A, Stewart JM, Arnold AC, Pace LA, Axelsson J, Boris JR, Moak JP, Goodman BP, Chémali KR, Chung TH, Goldstein DS (November 2021). "Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): State of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health Expert Consensus Meeting - Part 1". Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. 235: 102828. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828. ISSN 1566-0702. PMC 8455420. PMID 34144933.

- ^ a b Wells R, Paterson F, Bacchi S, Page A, Baumert M, Lau DH (June 2020). "Brain fog in postural tachycardia syndrome: An objective cerebral blood flow and neurocognitive analysis". Journal of Arrhythmia. 36 (3): 549–552. doi:10.1002/joa3.12325. PMC 7280003. PMID 32528589.

- ^ a b Ross AJ, Medow MS, Rowe PC, Stewart JM (December 2013). "What is brain fog? An evaluation of the symptom in postural tachycardia syndrome". Clinical Autonomic Research. 23 (6): 305–311. doi:10.1007/s10286-013-0212-z. PMC 3896080. PMID 23999934.

- ^ a b Raj SR, Fedorowski A, Sheldon RS (March 14, 2022). "Diagnosis and management of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". CMAJ. 194 (10): E378–E385. doi:10.1503/cmaj.211373. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 8920526. PMID 35288409.

- ^ Ferri FF (2016). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1019.e2. ISBN 978-0-323-44838-3. Archived from the original on 2023-09-06. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- ^ a b Raj SR, Arnold AC, Barboi A, Claydon VE, Limberg JK, Lucci VM, et al. (June 2021). "Long-COVID postural tachycardia syndrome: an American Autonomic Society statement". Clinical Autonomic Research. 31 (3): 365–368. doi:10.1007/s10286-021-00798-2. PMC 7976723. PMID 33740207.

- ^ a b c Blitshteyn S, Whitelaw S (April 2021). "Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other autonomic disorders after COVID-19 infection: a case series of 20 patients". Immunologic Research. 69 (2): 205–211. doi:10.1007/s12026-021-09185-5. PMC 8009458. PMID 33786700.

- ^ a b Blitshteyn S, Fedorowski A (12 December 2022). "The risks of POTS after COVID-19 vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 infection: it's worth a shot". Nature Cardiovascular Research. 1 (12): 1119–1120. doi:10.1038/s44161-022-00180-z. ISSN 2731-0590. S2CID 254617706.

- ^ Yong SJ, Halim A, Liu S, Halim M, Alshehri AA, Alshahrani MA, Alshahrani MM, Alfaraj AH, Alburaiky LM, Khamis F, Muzaheed, AlShehail BM, Alfaresi M, Al Azmi R, Albayat H, Al Kaabi NA, Alhajri M, Al Amri KA, Alsalman J, Algosaibi SA, Al Fares MA, Almanaa TN, Almutawif YA, Mohapatra RK, Rabaan AA (November 2023). "Pooled rates and demographics of POTS following SARS-CoV-2 infection versus COVID-19 vaccination: Systematic review and meta-analysis". Auton Neurosci. 250: 103132. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2023.103132. PMID 38000119. S2CID 265383080.

- ^ Sheldon RS, Grubb BP, Olshansky B, Shen WK, Calkins H, Brignole M, et al. (June 2015). "2015 heart rhythm society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope". Heart Rhythm. 12 (6): e41–e63. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029. PMC 5267948. PMID 25980576.

- ^ Graf N (2018). "Clinical Symptoms and Results of Autonomic Function Testing Overlap in Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension and Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome" (PDF). Cephalalgia Reports. 1: 1–6. doi:10.1177/2515816318773774. S2CID 79542947. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-04. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ Knight J (2018). "Effects of Bedrest: Introduction and the Cardiovascular System". Nursing Times. 114 (12): 54–57. Archived from the original on 2022-08-10. Retrieved 2022-08-10 – via EMAP.

- ^ a b c Fedorowski A (April 2019). "Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: clinical presentation, aetiology and management". Journal of Internal Medicine. 285 (4): 352–366. doi:10.1111/joim.12852. PMID 30372565.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Raj SR (June 2013). "Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS)". Circulation. 127 (23): 2336–2342. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.144501. PMC 3756553. PMID 23753844.

- ^ Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, Richer L, Schondorf R, Seifer C, et al. (March 2020). "Canadian Cardiovascular Society Position Statement on Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) and Related Disorders of Chronic Orthostatic Intolerance". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 36 (3): 357–372. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024. PMID 32145864.

- ^ Kizilbash SJ, Ahrens SP, Bruce BK, Chelimsky G, Driscoll SW, Harbeck-Weber C, et al. (2014). "Adolescent fatigue, POTS, and recovery: a guide for clinicians". Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care. 44 (5): 108–133. doi:10.1016/j.cppeds.2013.12.014. PMC 5819886. PMID 24819031.

- ^ Thieben MJ, Sandroni P, Sletten DM, Benrud-Larson LM, Fealey RD, Vernino S, et al. (March 2007). "Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: the Mayo clinic experience". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 82 (3): 308–313. doi:10.4065/82.3.308. PMID 17352367.

- ^ a b Kanjwal K, Karabin B, Sheikh M, Elmer L, Kanjwal Y, Saeed B, Grubb BP (June 2011). "Pyridostigmine in the treatment of postural orthostatic tachycardia: a single-center experience". Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 34 (6): 750–755. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03047.x. PMID 21410722. S2CID 20405336.

- ^ a b Chen L, Wang L, Sun J, Qin J, Tang C, Jin H, Du J (2011). "Midodrine hydrochloride is effective in the treatment of children with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". Circulation Journal. 75 (4): 927–931. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-10-0514. PMID 21301135.

- ^ Bhatia R, Kizilbash SJ, Ahrens SP, Killian JM, Kimmes SA, Knoebel EE, et al. (June 2016). "Outcomes of Adolescent-Onset Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome". The Journal of Pediatrics. 173: 149–153. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.02.035. PMID 26979650.

- ^ "Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS)". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 21 December 2022. Archived from the original on 13 November 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Lyonga Ngonge A, Nyange C, Ghali JK (February 2024). "Novel pharmacotherapeutic options for the treatment of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 25 (2): 181–188. doi:10.1080/14656566.2024.2319224. PMID 38465412.

- ^ a b Frye WS, Greenberg B (April 2024). "Exploring quality of life in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: A conceptual analysis". Auton Neurosci. 252: 103157. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2024.103157. PMID 38364354.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Mar PL, Raj SR (2014). "Neuronal and hormonal perturbations in postural tachycardia syndrome". Frontiers in Physiology. 5: 220. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00220. PMC 4059278. PMID 24982638.

- ^ a b c Freeman R, Wieling W, Axelrod FB, Benditt DG, Benarroch E, Biaggioni I, et al. (April 2011). "Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome". Clinical Autonomic Research. 21 (2): 69–72. doi:10.1007/s10286-011-0119-5. PMID 21431947. S2CID 11628648.

- ^ Khurana RK, Eisenberg L (March 2011). "Orthostatic and non-orthostatic headache in postural tachycardia syndrome". Cephalalgia. 31 (4): 409–415. doi:10.1177/0333102410382792. PMID 20819844. S2CID 45348885.

- ^ Stewart JM (May 2002). "Pooling in chronic orthostatic intolerance: arterial vasoconstrictive but not venous compliance defects". Circulation. 105 (19): 2274–2281. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000016348.55378.C4. PMID 12010910. S2CID 11618433.

- ^ Abou-Diab J, Moubayed D, Taddeo D, Jamoulle O, Stheneur C (2018-04-24). "Acrocyanosis Presentation in Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome". International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics. 7 (1–2): 13–16. doi:10.14740/ijcp293w. S2CID 55840690.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Mathias CJ, Low DA, Iodice V, Owens AP, Kirbis M, Grahame R (December 2011). "Postural tachycardia syndrome--current experience and concepts". Nature Reviews. Neurology. 8 (1): 22–34. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2011.187. PMID 22143364. S2CID 26947896.

- ^ a b c Raj SR (April 2006). "The Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): pathophysiology, diagnosis & management". Indian Pacing and Electrophysiology Journal. 6 (2): 84–99. PMC 1501099. PMID 16943900.

- ^ Mallien J, Isenmann S, Mrazek A, Haensch CA (2014-07-07). "Sleep disturbances and autonomic dysfunction in patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". Frontiers in Neurology. 5: 118. doi:10.3389/fneur.2014.00118. PMC 4083342. PMID 25071706.

- ^ Bagai K, Song Y, Ling JF, Malow B, Black BK, Biaggioni I, et al. (April 2011). "Sleep disturbances and diminished quality of life in postural tachycardia syndrome". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 7 (2): 204–210. doi:10.5664/jcsm.28110. PMC 3077350. PMID 21509337.

- ^ Haensch CA, Mallien J, Isenmann S (2012-04-25). "Sleep Disturbances in Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): A Polysomnographic and Questionnaires Based Study (P05.206)". Neurology. 78 (1 Supplement): P05.206. doi:10.1212/WNL.78.1_MeetingAbstracts.P05.206.

- ^ Pederson CL, Blettner Brook J (2017-04-12). "Sleep disturbance linked to suicidal ideation in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". Nature and Science of Sleep. 9: 109–115. doi:10.2147/nss.s128513. PMC 5396946. PMID 28442939.

- ^ "POTS: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 2021-11-12. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- ^ Raj V, Opie M, Arnold AC (December 2018). "Cognitive and psychological issues in postural tachycardia syndrome". Autonomic Neuroscience. 215: 46–55. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2018.03.004. PMC 6160364. PMID 29628432.

- ^ Arnold AC, Haman K, Garland EM, Raj V, Dupont WD, Biaggioni I, et al. (January 2015). "Cognitive dysfunction in postural tachycardia syndrome". Clinical Science. 128 (1): 39–45. doi:10.1042/CS20140251. PMC 4161607. PMID 25001527.

- ^ Anderson JW, Lambert EA, Sari CI, Dawood T, Esler MD, Vaddadi G, Lambert GW (2014). "Cognitive function, health-related quality of life, and symptoms of depression and anxiety sensitivity are impaired in patients with the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS)". Frontiers in Physiology. 5: 230. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00230. PMC 4070177. PMID 25009504.

- ^ Low PA, Novak V, Spies JM, Novak P, Petty GW (February 1999). "Cerebrovascular regulation in the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS)". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 317 (2): 124–133. doi:10.1016/s0002-9629(15)40486-0. PMID 10037116.

- ^ Novak P (2016). "Cerebral Blood Flow, Heart Rate, and Blood Pressure Patterns during the Tilt Test in Common Orthostatic Syndromes". Neuroscience Journal. 2016: 6127340. doi:10.1155/2016/6127340. PMC 4972931. PMID 27525257.

- ^ Ocon AJ, Medow MS, Taneja I, Clarke D, Stewart JM (August 2009). "Decreased upright cerebral blood flow and cerebral autoregulation in normocapnic postural tachycardia syndrome". American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 297 (2): H664–H673. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00138.2009. PMC 2724195. PMID 19502561.

- ^ Stewart JM, Del Pozzi AT, Pandey A, Messer ZR, Terilli C, Medow MS (March 2015). "Oscillatory cerebral blood flow is associated with impaired neurocognition and functional hyperemia in postural tachycardia syndrome during graded tilt". Hypertension. 65 (3): 636–643. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04576. PMC 4326551. PMID 25510829.

- ^ a b c Johnson JN, Mack KJ, Kuntz NL, Brands CK, Porter CJ, Fischer PR (February 2010). "Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: a clinical review". Pediatric Neurology. 42 (2): 77–85. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.07.002. PMID 20117742.

- ^ Kavi L, Gammage MD, Grubb BP, Karabin BL (June 2012). "Postural tachycardia syndrome: multiple symptoms, but easily missed". The British Journal of General Practice. 62 (599): 286–287. doi:10.3399/bjgp12X648963. PMC 3361090. PMID 22687203.

- ^ a b Kanjwal K, Saeed B, Karabin B, Kanjwal Y, Grubb BP (2011). "Clinical presentation and management of patients with hyperadrenergic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. A single center experience". Cardiology Journal. 18 (5): 527–531. doi:10.5603/cj.2011.0008. PMID 21947988.

- ^ a b c d Vernino S, Stiles LE (December 2018). "Autoimmunity in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: Current understanding". Autonomic Neuroscience. Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS). 215: 78–82. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2018.04.005. PMID 29909990.

- ^ Wilson RG (November 4, 2015). "Understanding POTS, Syncope and Other Autonomic Disorders". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Mallick D, Goyal L, Chourasia P, Zapata MR, Yashi K, Surani S. (March 31, 2023). "COVID-19 Induced Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): A Review". Cureus. 15 (3): e36855. doi:10.7759/cureus.36955. PMC 10065129. PMID 37009342.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gómez-Moyano E, Rodríguez-Capitán J, Gaitán Román D, Reyes Bueno JA, Villalobos Sánchez A, Espíldora Hernández F, González Angulo GE, Molina Mora MJ, Thurnhofer-Hemsi K, Molina-Ramos AI, Romero-Cuevas M, Jiménez-Navarro M, Pavón-Morón FJ (2023). "Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome and other related dysautonomic disorders after SARS-CoV-2 infection and after COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccination". Front Neurol. 14: 1221518. doi:10.3389/fneur.2023.1221518. PMC 10467287. PMID 37654428.

- ^ Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ (March 2023). "Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 21 (3): 133–146. doi:10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2. PMC 9839201. PMID 36639608. S2CID 255800506.

- ^ Dahan S, Tomljenovic L, Shoenfeld Y (April 2016). "Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS)--A novel member of the autoimmune family". Lupus. 25 (4): 339–342. doi:10.1177/0961203316629558. PMID 26846691.

- ^ Li H, Zhang G, Zhou L, Nuss Z, Beel M, Hines B, et al. (October 2019). "Adrenergic Autoantibody-Induced Postural Tachycardia Syndrome in Rabbits". Journal of the American Heart Association. 8 (19): e013006. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.013006. PMC 6806023. PMID 31547749.

- ^ Miglis MG, Muppidi S (February 2020). "Is postural tachycardia syndrome an autoimmune disorder? And other updates on recent autonomic research". Clinical Autonomic Research. 30 (1): 3–5. doi:10.1007/s10286-019-00661-5. PMID 31938977.

- ^ a b Kharraziha I, Axelsson J, Ricci F, Di Martino G, Persson M, Sutton R, et al. (August 2020). "Serum Activity Against G Protein-Coupled Receptors and Severity of Orthostatic Symptoms in Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome". Journal of the American Heart Association. 9 (15): e015989. doi:10.1161/JAHA.120.015989. PMC 7792263. PMID 32750291.

- ^ Gunning WT, Stepkowski SM, Kramer PM, Karabin BL, Grubb BP (February 2021). "Inflammatory Biomarkers in Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome with Elevated G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Autoantibodies". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 10 (4): 623. doi:10.3390/jcm10040623. PMC 7914580. PMID 33562074.

- ^ Yu X, Li H, Murphy TA, Nuss Z, Liles J, Liles C, et al. (April 2018). "Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor Autoantibodies in Postural Tachycardia Syndrome". Journal of the American Heart Association. 7 (8). doi:10.1161/JAHA.117.008351. PMC 6015435. PMID 29618472.

- ^ Gunning WT, Stepkowski SM, Kramer PM, Karabin BL, Grubb BP (February 2021). "Inflammatory Biomarkers in Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome with Elevated G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Autoantibodies". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 10 (4): 623. doi:10.3390/jcm10040623. PMC 7914580. PMID 33562074.

- ^ Bonamichi-Santos R, Yoshimi-Kanamori K, Giavina-Bianchi P, Aun MV (August 2018). "Association of Postural Tachycardia Syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome with Mast Cell Activation Disorders". Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. Mastocytosis. 38 (3): 497–504. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2018.04.004. PMID 30007466. S2CID 51628256.

- ^ Cheung I, Vadas P (2015). "A New Disease Cluster: Mast Cell Activation Syndrome, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 135 (2): AB65. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1146.

- ^ Kohn A, Chang C (June 2020). "The Relationship Between Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS)". Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 58 (3): 273–297. doi:10.1007/s12016-019-08755-8. PMID 31267471. S2CID 195787615.

- ^ Chang AR, Vadas P (2019). "Prevalence of Symptoms of Mast Cell Activation in Patients with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome and Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 143 (2): AB182. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2018.12.558.

- ^ a b c Carew S, Connor MO, Cooke J, Conway R, Sheehy C, Costelloe A, Lyons D (January 2009). "A review of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". Europace. 11 (1): 18–25. doi:10.1093/europace/eun324. PMID 19088364.

- ^ Dipaola F, Barberi C, Castelnuovo E, Minonzio M, Fornerone R, Shiffer D, et al. (August 2020). "Time Course of Autonomic Symptoms in Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) Patients: Two-Year Follow-Up Results". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17 (16): 5872. doi:10.3390/ijerph17165872. PMC 7460485. PMID 32823577.

- ^ McKeon A, Lennon VA, Lachance DH, Fealey RD, Pittock SJ (June 2009). "Ganglionic acetylcholine receptor autoantibody: oncological, neurological, and serological accompaniments". Archives of Neurology. 66 (6): 735–741. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2009.78. PMC 3764484. PMID 19506133.

- ^ Prior R (13 September 2020). "Months after Covid-19 infection, patients report breathing difficulty and fatigue". CNN. Archived from the original on 2020-09-26. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

Gahan and others with long-haul Covid-19 symptoms face a condition called postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, which refers to a sharp rise in heart rate that occurs when moving from a reclining to standing position. The pull of gravity causes blood to pool in the legs. This condition can cause dizziness, lightheadedness and fainting.

- ^ Eshak N, Abdelnabi M, Ball S, Elgwairi E, Creed K, Test V, Nugent K (October 2020). "Dysautonomia: An Overlooked Neurological Manifestation in a Critically ill COVID-19 Patient". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 360 (4): 427–429. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2020.07.022. PMC 7366085. PMID 32739039.

- ^ Parker W, Moudgil R, Singh T (2021-05-11). "Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome in six patients following covid-19 infection". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 77 (18_Supplement_1): 3163. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(21)04518-6. PMC 8091396.

- ^ "COVID-19 and POTS: What You Should Know". WebMD. Archived from the original on 2021-07-31. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ^ Lee J, Vernon SD, Jeys P, Ali W, Campos A, Unutmaz D, et al. (August 2020). "Hemodynamics during the 10-minute NASA Lean Test: evidence of circulatory decompensation in a subset of ME/CFS patients". Journal of Translational Medicine. 18 (1): 314. doi:10.1186/s12967-020-02481-y. PMC 7429890. PMID 32799889.

- ^ Sivan M, Corrado J, Mathias C (2022-08-08). "The adapted Autonomic Profile (aAP) home-based test for the evaluation of neuro-cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction" (PDF). ACNR, Advances in Clinical Neuroscience and Rehabilitation. doi:10.47795/qkbu6715. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-06-03. Retrieved 2023-05-16.

- ^ a b c d e Low PA, Sandroni P, Joyner M, Shen WK (March 2009). "Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS)". Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 20 (3): 352–358. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01407.x. PMC 3904426. PMID 19207771.

- ^ a b Jacob G, Shannon JR, Costa F, Furlan R, Biaggioni I, Mosqueda-Garcia R, et al. (April 1999). "Abnormal norepinephrine clearance and adrenergic receptor sensitivity in idiopathic orthostatic intolerance". Circulation. 99 (13): 1706–1712. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.99.13.1706. PMID 10190880.

- ^ Jacob G, Costa F, Shannon JR, Robertson RM, Wathen M, Stein M, et al. (October 2000). "The neuropathic postural tachycardia syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 343 (14): 1008–1014. doi:10.1056/NEJM200010053431404. PMID 11018167.

- ^ Lambert E, Lambert GW (2014). "Sympathetic dysfunction in vasovagal syncope and the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". Frontiers in Physiology. 5: 280. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00280. PMC 4112787. PMID 25120493.

- ^ Zhang Q, Chen X, Li J, Du J (December 2014). "Clinical features of hyperadrenergic postural tachycardia syndrome in children". Pediatrics International. 56 (6): 813–816. doi:10.1111/ped.12392. PMID 24862636. S2CID 20740649.

- ^ Crnošija L, Krbot Skorić M, Adamec I, Lovrić M, Junaković A, Mišmaš A, et al. (February 2016). "Hemodynamic profile and heart rate variability in hyperadrenergic versus non-hyperadrenergic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". Clinical Neurophysiology. 127 (2): 1639–1644. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2015.08.015. PMID 26386646. S2CID 6008891.

- ^ a b Grubb BP, Kanjwal Y, Kosinski DJ (January 2006). "The postural tachycardia syndrome: a concise guide to diagnosis and management". Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 17 (1): 108–112. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00318.x. PMID 16426415. S2CID 38915192.

- ^ Sandroni P, Opfer-Gehrking TL, McPhee BR, Low PA (November 1999). "Postural tachycardia syndrome: clinical features and follow-up study". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 74 (11): 1106–1110. doi:10.4065/74.11.1106. PMID 10560597.

- ^ Deng W, Liu Y, Liu AD, Holmberg L, Ochs T, Li X, et al. (April 2014). "Difference between supine and upright blood pressure associates to the efficacy of midodrine on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) in children". Pediatric Cardiology. 35 (4): 719–725. doi:10.1007/s00246-013-0843-9. PMID 24253613. S2CID 105235.

- ^ Nogués M, Delorme R, Saadia D, Heidel K, Benarroch E (August 2001). "Postural tachycardia syndrome in syringomyelia: response to fludrocortisone and beta-blockers". Clinical Autonomic Research. 11 (4): 265–267. doi:10.1007/BF02298959. PMID 11710800. S2CID 9596669.

- ^ a b c d e "2015 Heart Rhythm Society Expert Consensus Statement on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Postural Tachycardia Syndrome, Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia, and Vasovagal Syncope". Archived from the original on 2017-03-03. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- ^ Rahman M, Anjum F (April 27, 2023). Fludrocortisone. PMID 33232001. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ a b McDonald C, Frith J, Newton JL (March 2011). "Single centre experience of ivabradine in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". Europace. 13 (3): 427–430. doi:10.1093/europace/euq390. PMC 3043639. PMID 21062792.

- ^ a b Tahir F, Bin Arif T, Majid Z, Ahmed J, Khalid M (April 2020). "Ivabradine in Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: A Review of the Literature". Cureus. 12 (4): e7868. doi:10.7759/cureus.7868. PMC 7255540. PMID 32489723.

- ^ Kanjwal K (March 16, 2011). "Pyridostigmine in the Treatment of Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: A Single-Center Experience". Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 34 (6): 750–755. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03047.x. PMID 21410722. S2CID 20405336. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ "Central Adelaide Multidisciplinary Ambulatory Consulting Service (MACS) Outpatient Service" (PDF). Government of South Australia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-03-03. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- ^ "Meta-analysis suggests oral phenylephrine may be ineffective for nasal congestion as measured by nasal airway resistance". Archived from the original on 2017-03-03. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- ^ a b Lai CC, Fischer PR, Brands CK, Fisher JL, Porter CB, Driscoll SW, Graner KK (February 2009). "Outcomes in adolescents with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome treated with midodrine and beta-blockers". Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 32 (2): 234–238. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2008.02207.x. PMID 19170913. S2CID 611824.

- ^ Yang J, Liao Y, Zhang F, Chen L, Junbao DU, Jin H (2014-01-01). "The follow-up study on the treatment of children with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". International Journal of Pediatrics (in Chinese). 41 (1): 76–79. ISSN 1673-4408. Archived from the original on 2022-02-23. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- ^ Chen L, Du JB, Jin HF, Zhang QY, Li WZ, Wang L, Wang YL (September 2008). "[Effect of selective alpha1 receptor agonist in the treatment of children with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome]". Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi = Chinese Journal of Pediatrics. 46 (9): 688–691. PMID 19099860.

- ^ Khan M, Ouyang J, Perkins K, Somauroo J, Joseph F (2015). "Treatment of Refractory Postural Tachycardia Syndrome with Subcutaneous Octreotide Delivered Using an Insulin Pump". Case Reports in Medicine. 2015: 545029. doi:10.1155/2015/545029. PMC 4452321. PMID 26089909.

- ^ Hoeldtke RD, Bryner KD, Hoeldtke ME, Hobbs G (December 2006). "Treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome: a comparison of octreotide and midodrine". Clinical Autonomic Research. 16 (6): 390–395. doi:10.1007/s10286-006-0373-0. PMID 17036177. S2CID 22288783.

The two drugs had similar potencies; combination therapy was not significantly better than monotherapy.

- ^ a b Freitas J, Santos R, Azevedo E, Costa O, Carvalho M, de Freitas AF (October 2000). "Clinical improvement in patients with orthostatic intolerance after treatment with bisoprolol and fludrocortisone". Clinical Autonomic Research. 10 (5): 293–299. doi:10.1007/BF02281112. PMID 11198485. S2CID 20843222.

- ^ Gall N, Kavi L, Lobo MD (2021). Postural tachycardia syndrome: a concise and practical guide to management and associated conditions. Cham: Springer. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-3-030-54165-1. OCLC 1204143485.[page needed]

- ^ Coffin ST, Black BK, Biaggioni I, Paranjape SY, Orozco C, Black PW, et al. (September 2012). "Desmopressin acutely decreases tachycardia and improves symptoms in the postural tachycardia syndrome". Heart Rhythm. 9 (9): 1484–1490. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.05.002. PMC 3419341. PMID 22561596.

- ^ Fu Q, Vangundy TB, Shibata S, Auchus RJ, Williams GH, Levine BD (August 2011). "Exercise training versus propranolol in the treatment of the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". Hypertension. 58 (2): 167–175. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.172262. PMC 3142863. PMID 21690484.

- ^ Arnold AC, Okamoto LE, Diedrich A, Paranjape SY, Raj SR, Biaggioni I, Gamboa A (May 2013). "Low-dose propranolol and exercise capacity in postural tachycardia syndrome: a randomized study". Neurology. 80 (21): 1927–1933. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318293e310. PMC 3716342. PMID 23616163.

- ^ Raj SR, Black BK, Biaggioni I, Paranjape SY, Ramirez M, Dupont WD, Robertson D (September 2009). "Propranolol decreases tachycardia and improves symptoms in the postural tachycardia syndrome: less is more". Circulation. 120 (9): 725–734. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.846501. PMC 2758650. PMID 19687359.

- ^ Chen L, Du JB, Zhang QY, Wang C, Du ZD, Wang HW, et al. (December 2007). "[A multicenter study on treatment of autonomous nerve-mediated syncope in children with beta-receptor blocker]". Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi = Chinese Journal of Pediatrics. 45 (12): 885–888. PMID 18339272.

- ^ Moon J, Kim DY, Lee WJ, Lee HS, Lim JA, Kim TJ, et al. (July 2018). "Efficacy of Propranolol, Bisoprolol, and Pyridostigmine for Postural Tachycardia Syndrome: a Randomized Clinical Trial". Neurotherapeutics. 15 (3): 785–795. doi:10.1007/s13311-018-0612-9. PMC 6095784. PMID 29500811.

- ^ Barzilai M, Jacob G (July 2015). "The Effect of Ivabradine on the Heart Rate and Sympathovagal Balance in Postural Tachycardia Syndrome Patients". Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal. 6 (3): e0028. doi:10.5041/RMMJ.10213. PMC 4524401. PMID 26241226.

- ^ Hersi AS (August 2010). "Potentially new indication of ivabradine: treatment of a patient with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". The Open Cardiovascular Medicine Journal. 4 (1): 166–167. doi:10.2174/1874192401004010166. PMC 2995161. PMID 21127745.

- ^ Taub PR, Zadourian A, Lo HC, Ormiston CK, Golshan S, Hsu JC (February 2021). "Randomized Trial of Ivabradine in Patients With Hyperadrenergic Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 77 (7): 861–871. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.029. PMID 33602468. S2CID 231964388.

- ^ Raj SR, Black BK, Biaggioni I, Harris PA, Robertson D (May 2005). "Acetylcholinesterase inhibition improves tachycardia in postural tachycardia syndrome". Circulation. 111 (21): 2734–2740. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.497594. PMID 15911704.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT00409435 for "A Study of Pyridostigmine in Postural Tachycardia Syndrome" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Kpaeyeh J, Mar PL, Raj V, Black BK, Arnold AC, Biaggioni I, et al. (December 2014). "Hemodynamic profiles and tolerability of modafinil in the treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 34 (6): 738–741. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000221. PMC 4239166. PMID 25222185.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT01988883 for "Modafinil and Cognitive Function in POTS" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Kanjwal K, Saeed B, Karabin B, Kanjwal Y, Grubb BP (January 2012). "Use of methylphenidate in the treatment of patients suffering from refractory postural tachycardia syndrome". American Journal of Therapeutics. 19 (1): 2–6. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181dd21d2. PMID 20460983. S2CID 11453764.

- ^ a b Fedorowski A (2018). Camm JA, Lüscher TF, Maurer G, Serruys PW (eds.). Orthostatic intolerance: orthostatic hypotension and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/med/9780198784906.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-182714-3.

- ^ Ruzieh M, Dasa O, Pacenta A, Karabin B, Grubb B (2017). "Droxidopa in the Treatment of Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome". American Journal of Therapeutics. 24 (2): e157–e161. doi:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000468. PMID 27563801. S2CID 205808005.

- ^ Goldstein DS, Smith LJ (2002). NDRF Hans. The National Dysautonomia Research Foundation. Archived from the original on 2021-05-04. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ Agarwal AK, Garg R, Ritch A, Sarkar P (July 2007). "Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 83 (981): 478–480. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2006.055046. PMC 2600095. PMID 17621618.

- ^ Boris JR, Bernadzikowski T (December 2018). "Utilisation of medications to reduce symptoms in children with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". Cardiology in the Young. 28 (12): 1386–1392. doi:10.1017/S1047951118001373. PMID 30079848. S2CID 51922967.

- ^ Cui YX, DU JB, Zhang QY, Liao Y, Liu P, Wang YL, Qi JG, Yan H, Xu WR, Liu XQ, Sun Y, Sun CF, Zhang CY, Chen YH, Jin HF (October 2022). "[A 10-year retrospective analysis of spectrums and treatment options of orthostatic intolerance and sitting intolerance in children]". Beijing da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban (in Chinese). 54 (5): 954–960. doi:10.19723/j.issn.1671-167X.2022.05.024. PMC 9568388. PMID 36241239.

- ^ Wallman D, Weinberg J, Hohler AD (May 2014). "Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome and Postural Tachycardia Syndrome: A relationship study". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 340 (1–2): 99–102. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2014.03.002. ISSN 0022-510X. PMID 24685354. S2CID 37278826. Archived from the original on 2024-03-08. Retrieved 2023-12-18.

- ^ Schondorf R, Low PA (January 1993). "Idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: an attenuated form of acute pandysautonomia?". Neurology. 43 (1): 132–137. doi:10.1212/WNL.43.1_Part_1.132. PMID 8423877. S2CID 43860206.

- ^ Rodgers K (31 March 2015). "Nicola Blackwood: I'm battling a genetic mobility condition EhlersDanlos". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ "Hospitals: Listeria: Volume 798". hansard.parliament.uk. House of Lords Hansard. 17 June 2019. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2020. Baroness Blackwood of North Oxford makes four speeches (thus standing up four times) between 5:52 PM and 6:04 PM.

- ^ "House of Lords collapse 'no big deal'". BBC News. 25 June 2019. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

Further reading[edit]

- Kress S (2018). Power Over POTS. Bookbaby. ISBN 978-1-5439-0681-3.

- Goldstein DS (2016). Principles of Autonomic Medicine (PDF). Archived from the original on 2023-09-06. Retrieved 2020-09-15.

- Freeman M (2015). The Dysautonomia Project. Bardolf. ISBN 978-1-938842-24-5.