Oak Hill Industrial Academy (also known as the Alice Lee Elliott Memorial Academy or Elliott Academy) was founded as a day school and later became a boarding school for Choctaw Freedmen. It existed from 1878 to 1936. It was located in the far southeastern corner of the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma. The original location was in the southwest corner of Section 27 near the present-day Valliant, Oklahoma.[1] But in 1902 it was rebuilt in the northeast quarter of section 29 near the western line of McCurtain County, Indian Territory.[2] The school closed in 1936, and no evidence of it other than a historical marker remains.

Curriculum[edit]

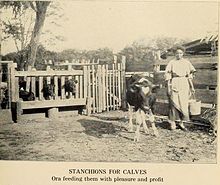

Oak Hill was developed to provide training in farming and domestic trades, and to teach Christianity to the former Choctaw slave children.[3] According to the school's founders, "[These young people] are transplanted for a time, where they may receive Bible instruction, industrial training and a foretaste of the privileges of an enlightened christian civilization".[4] As was typical of American Indian boarding schools the farming model was implemented, where students both learned agricultural and animal husbandry skills and grew their own food.[5] The students cultivated land, hauled water (as their well had run dry), and tended large herds of pigs and cattle.[6] In the early days, focus was on vocational training and the educational portion was minimal, as schooling beyond an eighth grade education was not offered.[7]

Shortly after Oklahoma's statehood, the school implemented a public school model for classes which included algebra, arithmetic, astronomy, bookkeeping, botany, chemistry, civics, composition, economics, geography, geology, geometry, grammar, history, literature, rhetoric, stenography, surveying, telegraphy, trigonometry, typewriting and zoology. In addition to the classroom studies, technical trades offered included agriculture, animal husbandry, apiculture, carpentry, cobbling, concrete work, domestics, gardening, laundry work, poultry raising, and sewing.[8] Though standardization of education was required, so was segregation. State laws passed in 1907 (the same year as statehood), provided that any person who included any quantum of African blood had to attend a colored school and imposed fines for anyone who allowed students of different racial mixtures to attend the same schools. All students without negro blood were to be considered white and identical separate but equal facilities were to be maintained.[9]

By 1912, the school was offering 6+1⁄2 to 7 hours of classroom study followed by 3 hours in the fields, sawing and splitting wood, or in the shop for boys and in the kitchen, laundry or sewing room for girls.[10] Bible study was required and students were expected to memorize one verse and read one chapter daily.[7] Between 1908 and 1912, 270 acres (1.1 km2) of land had been acquired and was under cultivation[11] and academic instruction was being offered up to the 12th grade.[8] In the early period of Oklahoma schooling there were few high schools and Elliott was listed as the only institution offering high school education to Choctaw freedmen's children.[12]

History[edit]

After the Civil War, Presbyterians established a church to do mission work among the Choctaw at Oak Hill around 1869, expanding it to include Sunday School in 1876.[13] When the Choctaw Nation freed their slaves and offered them citizenship, children of freedmen were entitled to benefit from the tribe's education fund.[14] The Choctaw nation allocated $2 for each Indian or Freedman student who "actually" attended school at least 15 days of every month. School attendance was mandatory and their system imposed fines of 10 cents per day on parents who did not send their children to school. The Nation provided all supplies and books and paid full or partial board for students who had to attend school away from their home communities.[15] White students were barred from attending the Indian schools and if, because of necessity, they attended the neighborhood schools (as opposed to agency assisted schools), they were charged full tuition.[16]

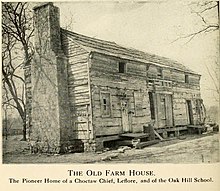

In 1878, a carpenter, George M. Dallas, was hired by the Presbyterian Board of Missions for Freedmen to build a schoolhouse and upon its completion began teaching a day school in the building.[14] In 1884, because there was an inadequate water supply, the school was transferred to a log house in section 29, about a mile and a half northwest of the original location.[17] In 1886, the Mission Board hired a teacher, Eliza Hartford from Steubenville, Ohio to take over instruction at the school. Hartford had previously taught in Cedar City, Utah[18] from 1881 to 1885.[19] With her arrival, the school relocated yet again to a log home which had formerly been the home of Chief LeFlore. Rather than stay with a church member and make the 3-mile journey to and from the school daily, Hartford moved into the school with 24 students on 15 April 1886, beginning the boarding school.[20] Due to illness Hartford resigned in 1889[21] but the girl's hall she had advocated for was completed.[22] In 1893 a boy's hall was completed and by 1895 both a laundry and smokehouse were built. In 1902, the schoolhouse was moved and a second story was added, so that it would be nearer the railway and water would not have to be hauled the 1+1⁄2 miles from the nearest water source,[23] Clear Creek, as the well on the property had run dry.[24]

In 1904, the school was closed during the Choctaw allotment and an arrangement made to secure 80 acres, 40 acres from two allottees, to reopen the school the following term.[25] When the school reopened in February 1905, in addition to the newly painted dorms, there were farm buildings supporting cattle, a dairy, a hen house, a farm, a garden, an orchard, and a piggery, which had been built and were maintained by the students.[26] In preparation for statehood, the Curtis Act of 1898 had provided that all tribal laws were to be abolished by 4 March 1906; however, as the state was not prepared to take over the educational system, Congress passed an Act on 26 April 1906 known as the Five Civilized Tribes Act, which effectively transferred supervision of all tribal schools to the Secretary of the Interior.[27] Effectively, this created a system whereby the eastern and western parts of the state continued to develop differently. In the east, the Five Civilized Tribes, including the Choctaw, did not have a ready means to tax land as the state education provisions required.[28] Due to this funding difference, missionary schools were phased out in western Indian schools by the time of statehood,[29] but continued in the eastern part of the state for many years.[30]

On 8 November 1908, the boy's dormitory was lost to fire and a temporary replacement was built by the students in 1909. In 1910, construction began on the permanent replacement building. The students and superintendent built the first steel reinforced concrete foundation in the territory, using sand from a nearby creek, rocks and bricks from previously burned buildings and iron from the "scrap pile".[31] On 13 March 1910, the girl's dormitory also burned and the students were forced to relocate to the original log house, which had been the first home of the boarding school. A donation of $5,000 was made by David Elliott[32] a prominent farmer from Lafayette, Indiana[33] for the replacement of the school buildings in the name of his deceased wife Alice Lee Elliott. Upon completion of Elliott Hall, the school was renamed the Alice Lee Elliott Memorial Academy, commonly called Elliott Academy, and was dedicated on 13 June 1912.[32] That same year, the first black administrator of the institution, William H. Carroll, was appointed superintendent.[34]

A Department of the Interior Bulletin published in 1916 lists the academy as a private school, at that time being wholly funded by the Presbyterian Mission Board. The school had 120 students, of whom 60 were boarders and 1 was above the 8th grade. It was also noted that of the 300 acres of land, only part of it was under cultivation for commercial purposes only and that it was not being used for educational purposes.[35] By the 1920 census there were 58 students under the age of 20 boarding at the school[36] but by 1930 only 10 boarding students remained.[37] Though the federal government's management of schools in the eastern part of the state was supposed to continue for only a few years, it did not fully cease for schools with Indian attendance until 1948.[38] The school was closed in 1936 and no evidence of it other than a historical marker remains.[39]

Notable alumni[edit]

- Reverend Wiley Homer, founder of Beaver Dam Church in Grant, Indian Territory[40]

- Edward D. Jones,[41] continued his education at the Leonard Medical School of Raleigh, NC[42] and became a physician in Nowata, Oklahoma[43]

- Johnson Shoals, continued his education at Tuskegee and Iowa State Agricultural College before returning to teach at Oak Hill Academy[44]

References[edit]

- ^ Flickinger, Robert Elliott (1914). The Choctaw Freedmen and The Story of Oak Hill Industrial Academy. Presbyterian Board of Missions for Freedmen. pp. 101–102. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ Flickinger (1914), pp 220–221

- ^ Flickinger (1914), p 135

- ^ Flickinger (1914), p 152

- ^ Bosworth, Dee Ann. "American Indian Boarding Schools: An Exploration of Global, Ethnic & Cultural Cleansing" (PDF). www.sagchip.org. Mount Pleasant, Michigan: The Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture & Lifeways. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ Flickinger (1914), pp 136–140

- ^ a b Greene, Hazel B. (17 February 1938). "An Interview with Mr. Jordan D. Folsom" (PDF). Indian and Pioneer Papers (12967). University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma: Western History Collections: 11–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ a b Flickinger (1914), p 270

- ^ Miller, Henry J. (compiler) (1912). School Laws of Oklahoma 1912. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: Jasper Sipes Company. pp. 56–58. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ Flickinger (1914), pp 162–166

- ^ Flickinger (1914), p 203

- ^ Goins, Charles Robert; Goble, Danney (2006). Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (4. ed.). Norman, Okla.: Univ. of Oklahoma Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8061-3482-6.

- ^ Baker, Terri M.; Henshaw, Connie Oliver, eds. (2007). Women who pioneered Oklahoma : stories from the WPA narratives. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-8061-3845-9. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ a b Flickinger (1914), p 103

- ^ Wellemeyer, John Fletcher (August 1914). "The Development of the Educational System in Oklahoma". University of Chicago Libraries. pp. 16–18. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ Wellemeyer (1914), p 26

- ^ Flickinger (1914), p 104

- ^ "Chapter 15: Religious Expression" (PDF). J. Willard Marriott Digital Library, University of Utah: History of Iron County (Utah). p. 273. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ Burton, Fred (compiler) (19 October 2006). "Teachers of Presbyterian Schools in Utah and Idaho" (PDF). Westminster College. Salt Lake City, Utah. pp. 35–36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ Flickinger (1914), pp 107–110

- ^ Flickinger (1914), p 112

- ^ Flickinger (1914), p 132

- ^ Flickinger (1914), pp 135–136

- ^ Flickinger (1914), p 139

- ^ Flickinger (1914), p 154

- ^ Flickinger (1914), pp 158–159

- ^ Wellemeyer (1914), p 44

- ^ Wellemeyer (1914), pp 52–55

- ^ Thiesen, Barbara A (June 2006). "Every Beginning Is Hard: Darlington Mennonite Mission, 1880–1902". Mennonite Life. 61 (2). Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ Jackson, Joe C. (1951). "Survey of Education in Eastern Oklahoma from 1917 to 1915" (PDF). Chronicles of Oklahoma. 29 (2). Oklahoma State University: Oklahoma Historical Society: 217. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Flickinger (1914), p 208

- ^ a b Flickinger (1914), pp 210–215

- ^ Biographical record and portrait album of Tippecanoe County, Indiana. Chicago, Illinois: Lewis Publishing Company. 1888. pp. 522–523. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ Cassity, Michael; Goble, Danney (2009). Divided hearts : the Presbyterian Journey Through Oklahoma History. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-8061-3848-0.

- ^ "Negro Education: A Study of the Private and Higher Schools for Colored People in the United States—Oklahoma". The Education of Racial Groups. II (39). Washington, DC: Department of the Interior Bureau of Education: 466–467. 1916. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "1920 United States Census, Wilson Township, McCurtain County, OK". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. U.S. National Archives. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "1930 Census of the United States, Wilson Township, McCurtain County, Oklahoma". archive.org. U. S. National Archives. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Jackson (1951), p 208

- ^ Walton-Raji, Angela Y. (27 February 2011). "Remembering Oak Hill Academy for Choctaw Freedmen". The African-Native American Genealogy Blog. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Flickinger (1914), pp362-369 103

- ^ Flickinger (1914), pp 149–150

- ^ "Twenty-Eighth Annual Catalog Of The Officers And Students Leonard Medical School". Raleigh, North Carolina: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company. 1908. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ "Edward Dager Jones United States World War I Draft Registration Cards". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. U.S. National Archives. 12 September 1918. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ Flickinger (1914), p 149