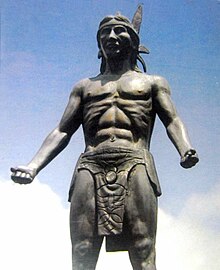

Nahua community in Rivas, Nicaragua. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 20,000+ | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Western Nicaragua and northwestern Costa Rica | |

| Estimated 20,000[1][2] | |

| ~1000 | |

| Languages | |

| Nawat, Nicaraguan Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Nahuas, Pipil people, Mexica | |

The Nicarao are a Nahua people who live in western Nicaragua and northwestern Costa Rica.[3][4][5][6][7][8] They spoke the Nahuat language before it went extinct in both countries.[9][10]

The Nicarao are descended from Toltecs who migrated from North America and central and southern Mexico over the course of several centuries from approximately 700 CE onwards.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19] There is some evidence to suggest this branch of the Nahua originated in Chiapas and the Yucatan.[20][21][22][23] Around 1200 CE, the Nicarao split from the Pipil people and moved into what is now Nicaragua.[24] The migration of the Nicarao has been linked to the collapse of the important central-Mexican cities of Teotihuacan and Tula, as well as the Classic Maya collapse. The Nicarao settled throughout western Nicaragua, such as Rivas, Jinotega, Chinandega, Nueva Segovia, Tiger Lagoon, Lake Xolotlan, Lake Nicaragua, Ometepe Island, Zapatera Island, Matagalpa, Esteli, and parts of Leon, Granada and Managua.[25][26][27][28][29][30] The Nicarao also settled in Bagaces, Costa Rica after displacing the Huetar people who were already there, resulting in tribal warfare between the Nahuas and the Huetares which lasted until Spanish arrival.[31][32] As a Mesoamerican group, the Nicarao shared many blended cultural traits with both indigenous North American and Mexican belief systems as well as their Toltec parent tribe, including an identical Toltec calendar, similar organizational treaties, the use of screenfold books, the worship of the Great Spirit and closely related sky deities, Nagual mysticism, the practice of animal and Tonal spirituality, and expertise in medical practice.[33][34][35][36][37]

History and Spanish contact[edit]

After the Nicarao split from their sister tribe and migrated further south into what is now western Nicaragua and northwestern Costa Rica, they waged war and displaced many neighboring tribes including the Cacaopera, the Chorotega, and the Huetares.[38][39][40] The Nicaraos also enslaved and captured Cacaoperas for human sacrifice and further displaced them from Jinotega, Esteli, Boaco, and parts of Matagalpa, particularly the Sebaco valley, one of the most fertile areas in Nicaragua which the Nicarao still inhabit today.[41][42][43][44] Although the Nicarao displaced rival tribes through warfare, they also developed trade relations with smaller tribes, maintaining hegemony over the region through military superiority and commerce.[45] At the time of Spanish contact the Nicarao were ruled by a cacique that the Spanish called Nicarao, whose real name was Macuilmiquiztli, meaning "Five Deaths" in the Nahuatl language.[46][47][48][49] Macuilmiquiztli governed the Nicarao from his capital Quauhcapolca, not far from the modern town of Rivas.[50] Seemingly not understanding the threat, Macuilmiquiztli initially welcomed the Spanish and their Tlaxcalan translators, but later waged war against the invaders. Nicarao warriors forced the Spanish to withdraw back to Panama.[51][52] The Nicarao hegemony over the region came to an end during the Spanish conquest of Nicaragua in 1524 CE, resulting in the Nicarao experiencing a devastating demographic and societal collapse from a combination of disease, war against the Spanish and their Tlaxcalan allies, and being sold into slavery.[53][54]

Origin and distribution[edit]

The Nicarao people migrated south from North America and central and southern Mexico over the course of several centuries from approximately 700 CE onwards. Around 1200 CE, the Nicarao split from the Pipil people and moved into what is now Nicaragua. The beginning of this series of migrations was likely to have been linked to the collapse of the great central-Mexican city of Teotihuacan, and later with the collapse of the Toltec city of Tula.[55] The dating of Nicarao arrival in what is now Nicaragua has also been linked to the Classic Maya collapse, with the cessation of Maya influence in the region, and the rise of cultural traits originating in the Valley of Mexico.[56] The Nicarao had a sizeable population concentrated in nucleated villages all over western Nicaragua and what is now northwestern Costa Rica.[57][58] They displaced both the Chorotega and the Cacaopera that had previously settled the region.[59] The Nicarao appear to have seized control of the most productive land around the western portions of Lake Nicaragua, and the Gulf of Fonseca.[60] The area now covered by Rivas Department appears to have been conquered by the Nicarao shortly before the Spanish conquest.[61][34]

A remnant Nahuat-speaking population existed as late as the mid-19th century, but the Nicarao as a tribal Confederation are now extinct.[57] Today Nicaragua is estimated to have around 20,000 Nicarao people. In Costa Rica the Nicarao population ranges from several hundred to 1000 and are primarily located in the Bagaces Canton, with smaller pockets inhabiting other parts of Guanacaste. Some of their practices and beliefs continue to survive among their descendants within the Nahua communities of Nicaragua and Costa Rica.

Major settlements[edit]

At the time of contact with the Spanish, the Nicarao were governed from their capital at Quauhcapolca, near the modern town of Rivas. Other principal settlements included Ometepe, Asososca Lagoon (Managua), Mistega, Ochomogo, Oxmorio, Papagayo, Tecoatega, Teoca, Totoaca, and Xoxoyota.[62]

Culture[edit]

Like most other Nahua groups, the Nicarao were agriculturalists, and cultivated maize, cacao, tomatoes, avocados, squash, beans, and chili.[63][64][65][66][67] Chocolate was fundamental to Nicarao culture as it was drank during special ceremonies in addition to cocoa beans being used as their currency.[68] The Nicarao also dined on various meats such as turkey, deer, iguana, mute dogs, and fish from the sea, rivers, lakes and lagoons.[69][70] The Nicarao had elaborate markets and permanent temples indicating some level of expertise in architecture, which have since been completely destroyed by the Spanish.[71][72] Although not much is known about Nicarao military structure, they did in fact have a warrior tradition. Nicarao warriors wore thick padded cotton armor, fought with spears, atlatls, bow and arrows, clubs edged with stone blades and macanas, a wooden sword edged with obsidian blades similar to the Aztec macahuitl.[73][74] Spanish chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, writing soon after the conquest, recorded that the Nicarao practised cranial modification, by binding the heads of young children between two pieces of wood. Archaeologists have unearthed pre-Columbian burials in the former Nicarao region with evidence of both cranial and dental modification.[75] The Nicarao possessed a number of cultural traits in common with North American tribes as well as the Toltecs of central Mexico, including an identical calendar, the use of screenfold books, worship of the Great Spirit and a Toltec pantheon of deities such as sky spirits, animal spirits and Tonal mythology, Nagual mysticism, and treaties.[76][77][35] They also, in common with their Mexican cousins from Aztec culture, practiced ritual confession, and the volador (flying men) ritual.[78][79]

Legacy[edit]

Despite their massive decrease in population and the loss of their native language, the Nicarao, and their culture, are still an integral part of Nicaraguan identity. Most Nicaraguans have Nahua ancestry, as proven through DNA analysis.[80][81] Towns, lakes, islands, and volcanoes bear their place names.[82] Nicaraguan Spanish has been heavily influenced by their native language.[83][84][85][86][87][88] Nicaraguan cuisine such as the nacatamal which originated from the Nicarao has also cemented itself in the legacy of Nicaraguan gastronomy.[89][90][91]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Indigenous peoples in Nicaragua".

- ^ Nicaragua. https://minorityrights.org/country/nicaragua/

- ^ Newson, Linda A.; Bonilla, Adolfo (2021). Las culturas indígenas y su medioambiente. Uol Insti for the Study of the Americas. pp. 21–54. ISBN 978-1-908857-87-3. JSTOR j.ctv1qr6sk7.7.

- ^ "Central American Nahua".

- ^ "The Kingdom of this world".

- ^ Peralta, De; M, Manuel (1901). "The Aboriginals of Costa Rica". Journal de la Société des Américanistes. 3 (2): 125–139. doi:10.3406/jsa.1901.3365.

- ^ "Do you know the origin of the word Guanacaste". 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Guanacaste is a practically autonomous ethnolinguistic area and different from the rest of the country". 22 July 2020.

- ^ Mc Callister, Rick (2013). "Náwat – y no náhuatl. El náwat centroamericano y sus sabores: Náwat pipil y náwat nicarao". Revista Caratula.

- ^ Constenla Umaña, Adolfo (1994). "Las lenguas de la Gran Nicoya". Revista Vínculos. 18–19. Museo Nacional de Costa Rica: 191–208.

- ^ "Nicarao".

- ^ "Migraciones de lengua Náhuatl hacia Centroamérica".

- ^ Brinton, Daniel G. (1887). "Were the Toltecs an Historic Nationality". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 24 (126): 229–241. JSTOR 983071.

- ^ "Las migraciones nahuas de México a Nicaragua según las fuentes históricas". 29 April 2006.

- ^ "The pre-Hispanic Indigenous cultures of Nicaragua and Costa Rica" (PDF).

- ^ "The pre-Hispanic World of Nicaragua" (PDF).

- ^ "Ensayos Nicaragüenses" (PDF).

- ^ "National Autonomous University of Nicaragua" (PDF).

- ^ "The Toltecs".

- ^ Campbell, Lyle (January 1, 1985). The Pipil Language of El Salvador. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 10–12. ISBN 978-3-11-088199-8.

- ^ Macri, Martha J.; Looper, Matthew G. (2003). "NAHUA IN ANCIENT MESOAMERICA: Evidence from Maya inscriptions". Ancient Mesoamerica. 14 (2): 285–297. doi:10.1017/S0956536103142046. JSTOR 26308175. S2CID 162601312.

- ^ "Chichen Itza: The Tollan of the Yucatan".

- ^ "Toltec".

- ^ Fowler 1985, p. 37.

- ^ "National Autonomous University of Nicaragua" (PDF).

- ^ "Nahoas. Territorio indígena y gobernanza".

- ^ "Laguna de Asososca: The Ultimate Guide to This Hidden Gem". 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Laguna de Asososca o Laguna del Tigre".

- ^ "Nicaraguan Anthropology". 31 March 2007. Archived from the original on 2016-08-09.

- ^ "Culture of Esteli". 26 August 2020.

- ^ Brinton, Daniel G. (1897). "The Ethnic Affinities of the Guetares of Costa Rica". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 36 (156): 496–498. JSTOR 983406.

- ^ Rojas, Eugenia Ibarra (2011). "The Nicarao, The Voto Indians and the Huetares In Conflict". Cuadernos de Antropología. 21.

- ^ Eagle, Obsidian (2020-11-25). "Who Were The Toltecs?". Medium. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- ^ a b Manion, Jessica (2016). "Remembering the Ancestors: Mortuary Practices and Social Memory in Pacific Nicaragua" (PDF). University of Calgary. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Frost, Melissa June (August 10, 2017). "Herbs That Madden, Herbs That Cure: A History of Hallucinogenic Plant Use in Colonial Mexico" (PDF). University of Virginia. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ Fowler, William R. (1989-01-01). "The Cultural Evolution of Ancient Nahua Civilizations The Pipil Nicarao of Central America". The Cultural Evolution of Ancient Nahua Civilizations the Pipil Nicarao of Central America.

- ^ De Burgos, Hugo (2014). "Contemporary Transformations of Indigenous Medicine and Ethnic Identity". Anthropologica. 56 (2): 399–413. JSTOR 24467313.

- ^ Brinton, Daniel G. (1897). "The Ethnic Affinities of the Guetares of Costa Rica". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 36 (156): 496–498. JSTOR 983406.

- ^ Rojas, Eugenia Ibarra (2011). "The Nicarao, The Voto Indians and the Huetares In Conflict". Cuadernos de Antropología. 21.

- ^ Fowler, William R. (1985). "Ethnohistoric Sources on the Pipil-Nicarao of Central America: A Critical Analysis". Ethnohistory. 32 (1): 37–62. doi:10.2307/482092. JSTOR 482092.

- ^ Ibarra Rojas, 1994, p. 236

- ^ "Nahoas. Territorio indígena y gobernanza".

- ^ "Naked Boaco".

- ^ "Culture of Esteli". 26 August 2020.

- ^ "Nicarao".

- ^ "Nicarao"

- ^ "Encuentro"

- ^ Sánchez, Edwin (October 3, 2016). "De Macuilmiquiztli al Güegüence pasando por Fernando Silva" [From Macuilmiquizli to Güegüence through Fernando Silva]. El 19 (in Spanish). Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ Silva, Fernando (March 15, 2003). "Macuilmiquiztli". El Nuevo Diario (in Spanish). Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ McCafferty and McCafferty 2009, p. 186.

- ^ "Fruit and Axes of Gold Consuming Indigenous Heritages in Nicaragua".

- ^ "The Testimonies and Origins of the Nicaraos" (PDF).

- ^ "The Tlaxcalan Memory of the Conquest".

- ^ "Nicarao".

- ^ Fowler 1985, p. 37. Healy 1980, 2006a, p. 339.

- ^ Healy 1980, 2006a, p. 337.

- ^ a b Fowler 1985, p. 38.

- ^ Healy 1980, 2006a, p.338.

- ^ McCafferty and McCafferty 2009, p. 186.

- ^ Salamanca 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Healy 1980, 2006a, p. 336.

- ^ Healy 1980, 2006b, p. 21.

- ^ Fowler, 1989

- ^ "Chocolate in Mesoamerica A Cultural History of Cacao" (PDF).

- ^ "Costa Rican Archaeology and Mesoamerica" (PDF).

- ^ Bergmann, John F. (1969). "The Distribution of Cacao Cultivation in Pre-Columbian America". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 59 (1): 85–96. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1969.tb00659.x. JSTOR 2569524.

- ^ "NICARAO AND CHOROTEGA GASTRONOMY OF THE 16TH CENTURY" (PDF).

- ^ "NICARAO AND CHOROTEGA GASTRONOMY OF THE 16TH CENTURY" (PDF).

- ^ "NICARAO AND CHOROTEGA GASTRONOMY OF THE 16TH CENTURY" (PDF).

- ^ "Nicaraguan Themes" (PDF).

- ^ "The Kingdom Of This World".

- ^ "Costa Rican Archaeology and Mesoamerica" (PDF).

- ^ Fowler, William R. (1989-01-01). "The Cultural Evolution of Ancient Nahua Civilizations The Pipil Nicarao of Central America". The Cultural Evolution of Ancient Nahua Civilizations the Pipil Nicarao of Central America.

- ^ "Costa Rican Archaeology and Mesoamerica" (PDF).

- ^ McCafferty and McCafferty 2009, p. 188.

- ^ McCafferty 2015, p. 111.

- ^ Manion, Jessica (2016). "Remembering the Ancestors: Mortuary Practices and Social Memory in Pacific Nicaragua" (PDF). University of Calgary. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ Healy 1980, 2006b, p. 31.

- ^ Frühsorge, Lars (2010). "Unwrapping the Sacred Bundle: Problems of Cultural Continuity and Regional Diversity in the Study of Ancient Maya Deities". University of Hamburg. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ Nuñez, C.; Baeta, M.; Sosa, C.; Casalod, Y.; Ge, J.; Budowle, B.; Martínez-Jarreta, B. (2010). "Reconstructing the population history of Nicaragua by means of mtDNA, Y-chromosome STRs, and autosomal STR markers". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 143 (4): 591–600. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21355. PMID 20721944.

- ^ "Reconstructing the Population History of Nicaragua by Means of mtDNA, Y-Chromosome STRs, and Autosomal STR Markers" (PDF).

- ^ "Nahuatl Placenames In Nicaragua". 25 August 2018.

- ^ "Pipil Words Identified in Nicaraguan Speech" (PDF).

- ^ Elliott, A. M. (1884). "The Nahuatl-Spanish Dialect of Nicaragua". The American Journal of Philology. 5 (1): 54–67. doi:10.2307/287421. JSTOR 287421.

- ^ "2 Ways Nahuatl Helped Shape Nicaraguan Spanish".

- ^ Úbeda, Zobeyda Catalina Zamora. "Current situation of the Nahuatl substrate in Nicaraguan Spanish". Revista Lengua y Literatura. 6 (1): 43–51.

- ^ Zamora Úbeda, Zobeyda C. (2022). "El sustrato náhuatl en el español de Nicaragua según el Diccionario de la lengua española". Lengua y Sociedad. 21 (2): 13–26. doi:10.15381/lengsoc.v21i2.22516.

- ^ "Situación actual del sustrato náhuatl en el español de Nicaragua".

- ^ "THE ACCULTURATION OF THE NICARAO NATIVES IN NICARAGUA".

- ^ "The Nicaraguan Nacatamal".

- ^ "Five Traditional Nicaraguan Food You Must Try".

References[edit]

- Fowler, William R. Jr. (Winter 1985). "Ethnohistoric Sources on the Pipil-Nicarao of Central America: A Critical Analysis". Ethnohistory. Duke University Press. 32 (1): 37–62. ISSN 0014-1801. JSTOR 482092. OCLC 478130795. Retrieved 2017-06-27. (Full text via JSTOR.)

- Isla de Ometepe, la mayor isla del mundo en un lago de agua dulce. https://www.visitcentroamerica.com/visitar/isla-ometepe/

- Healy, Paul (2006a) [1980]. A Proposed Culture History of the Rivas Region in Archaeology of the Rivas Region, Nicaragua. pp. 329–341. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-094-7. (Full text via Project MUSE.)

- Healy, Paul (2006b) [1980]. A Brief History of the Culture Subarea in Archaeology of the Rivas Region, Nicaragua. pp. 19–34. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-094-7. (Full text via Project MUSE.)

- McCafferty, Geoffrey G.; and McCafferty, Sharisse D. (2009). "Crafting the Body Beautiful: Performing Social Identity at Santa Isabel, Nicaragua" in Halperin, Christina T., Katherine A. Faust, Rhonda Taube, Aurore Giguet, Elizabeth M. Brumfiel, and Lisa Overholtzer (eds.). Mesoamerican Figurines. pp. 297–323. Gainesville, Florida, US: University Press of Florida. Archived from the original on 2017-07-17. ISBN 978-0-8130-3330-3.

- Nahoas. Territorio Indigena y Gobernanza. https://www.territorioindigenaygobernanza.com/web/nnic_09/

- McCafferty, Geoffrey (2015). "The Mexican Legacy in Nicaragua, or Problems when Data Behave Badly". Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 25 (1): 110–118. *Salamanca, Danilo (2012) "Los dos rostros indígenas de Nicaragua y Centroamérica". Wani, Revista del Caribe Nicaragüense. 65: 6–23. Bluefields, Nicaragua: Bluefields Indian & Caribbean University/Centro de Investigaciones y Documentacion de la Costa Atlántica (BICU/CIDCA). ISSN 2308-7862. (in Spanish)