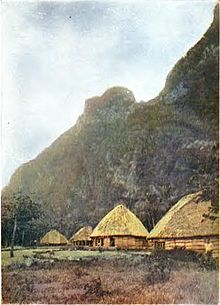

The islands of Samoa were originally inhabited by humans as early as 850 BC. After being invaded by European explorers in the 18th century, by the 20th and 21st century, the islands were incorporated into Samoa (Western Samoa, Independent Samoa) and American Samoa (Eastern Samoa).

Early history of the Polynesian people of Samoa[edit]

The pre-colonial history of Eastern Samoa (now American Samoa) is inextricably bound with the history of Western Samoa (now independent Samoa).

The Tui Manu'a is one of the oldest Samoan titles in Samoa. Traditional oral literature of Samoa and Manu'a talks of a widespread Polynesian network or confederacy (or "empire") that was prehistorically ruled by the successive Tui Manu'a dynasties. Manuan genealogies and religious oral literature also suggest that the Tui Manu'a had long been one of the most prestigious and powerful paramounts Samoa. Legends suggest that the Tui Manu'a kings ruled a confederacy of far-flung islands which included Fiji, Tonga[1] as well as smaller western Pacific chiefdoms and Polynesian outliers such as Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau, and Tuvalu. Commerce and exchange routes between the western Polynesian societies is well documented and it is speculated that the Tui Manu'a dynasty grew through its success in obtaining control over the oceanic trade of currency goods such as finely woven ceremonial mats, whale ivory "tabua", obsidian and basalt tools, chiefly red feathers, and seashells reserved for royalty (such as polished nautilus and the egg cowry).

The islands of Upolu and Savai'i were politically connected to 'Upolu island in what is now independent Samoa. It can be said that all the Samoa islands are politically connected today through the faamatai chiefly system and through family connections that are as strong as ever. This system of the faamatai and the customs of faasamoa originated with two of the most famous early chiefs of Samoa, who were both women and related, Nafanua and Salamasina.

Arrival of Western missionaries[edit]

Early Western contact included a battle in the 18th century between French explorers and islanders in Tutuila, for which the Samoans were blamed in the West, giving them a reputation for ferocity. Early 19th-century Rarotongan missionaries to the Samoa islands were followed by a group of Western missionaries led by John Williams of the (Congregationalist) London Missionary Society in the 1830s, officially bringing Christianity to Samoa. Less than a hundred years later, the Samoan Congregationalist Church became the first independent indigenous church of the South Pacific.

European and American colonial division of the Samoan archipelago[edit]

Initial American interest began midway through the 19th century when an 1838 U.S. whaling expedition reported on the commercial value of Pago Pago Bay. The U.S. was interested in gaining access to Samoan resources, particularly coconut oil and copra.

Union blockade of Confederate sugar and cotton exports during the American Civil War (1861–65) provoked expansion into Samoa. Surging global demands for Cotton and the need for economic recovery in the South following the war, made Samoa a prime candidate for Cotton plantations.[2]

Whilst, the U.S. Congress had initially been reluctant to establish a formal ties with Samoa, fears that the islands would be lost to Germany and Britain caused a shift in their attitudes. In 1872, an informal treaty was signed between the U.S. and Samoan chiefs. A second treaty was later signed in response to German and British plans to establish a protectorate over Samoa. The treaty of friendship was signed between the U.S. and Samoan leaders in 1878, which gave the U.S. rights to establish a naval coaling station at Pago Pago Bay and freedom of commerce in other Samoan ports.[3]

American Samoa is the result of the Second Samoan Civil War and an agreement made between Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom in the Tripartite Convention of 1899. The international rivalries were settled by the 1899 Treaty of Berlin in which Germany and the U.S. divided the Samoan archipelago. The eastern Samoan islands became territories of the United States and later became known as American Samoa. The U.S. formally occupied its portion, with the noted harbor of Pago Pago, the following year. The western islands are now the independent state of Samoa.

Colonization by the United States[edit]

Several chiefs of the island of Tutuila swore allegiance, and ceded the island, to the United States in the Treaty of Cession of Tutuila of 1900. The last sovereign of Manuʻa, the Tui Manuʻa Elisara, signed the Treaty of Cession of Manuʻa of 1904 following a series of US Naval trials, known as the "Trial of the Ipu", in Pago Pago, Taʻu, and aboard a Pacific Squadron gunboat. The treaties were ratified by the United States in the Ratification Act of 1929.

After World War I, during the time of the Mau movement in Western Samoa (then a New Zealand protectorate), there was a corresponding American Samoa Mau movement, led by Samuel Sailele Ripley, who was from Leone village and was a World War I war veteran. In 1921, seventeen chiefs of the American Samoa Mau were arrested and imprisoned under hard labor.

During World War II, U.S. Marines in American Samoa outnumbered the local population, having a huge cultural influence. Young Samoan men from the age of 14 and above were combat trained by US military personnel. As in World War I, American Samoans served in World War II as combatants, medical personnel, code personnel, ship repairs, etc.

Racial aspects of colonization[edit]

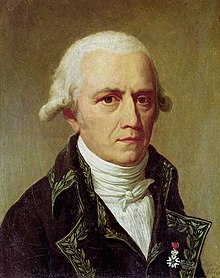

Lamarckian theory of the inheritance of acquired characteristics was applied by American officials in their categorisation of the Samoan people. When discussing the Samoans as a "race", the first governor of Samoa, B.F. Tilly charged that they were "still a patriarchal state". Other officials claimed they "lacked character" and "seriousness". The perceived inferiority of the Samoan people compared to their white American counterparts was deemed the result of environmental rather than biological factors. American officials believed that the natural environment of the Samoan islands meant that for generations they had been without hardship and required to complete little work. Consequently, they failed to develop traits present in the White Americans.[4]

American officials in Samoa also romanticised the native Samoans. In 1901, the governor praised them as "amiable" and "fine-looking and courtly". In 1904, they were described as a "gentle, kindly, simple-minded race [who] are easily governed". The Samoans were placed higher than Black people in the racial hierarchy. In 1913, the Governor of Samoa claimed "There is nothing about them to suggest the negro". He praised the physical stature of Samoan men, describing them as "a very handsome race of men".[4]

Race and reluctance to incorporate Samoa into the United States[edit]

White supremacy was important in the U.S. government's reluctance to formally annex Samoa. Under the U.S. Constitution, any new territory secured by the federal government would subsequently have to be incorporated into the United States as a state. If this were to happen, this would grant equal citizenship rights to non-white individuals in Pacific island territories. Consequently, when Samoan chiefs wrote to President Ulysses S. Grant in 1873 asking him to formally annex Samoa in order to protect their territory from Britain and Germany, this was rejected by Congress. Racism was also a key factor in Congress' initial opposition to naval expansion during the 1870s.[3]

The Insular Cases and the constitutional legitimation of American colonization[edit]

In the wake of the Spanish-American War (1898), capturing territories like Puerto Rico and the Philippines, U.S. legal actors crafted a novel approach to governing these new possessions. This territorial policy, distinct from past precedents, aimed to establish U.S. dominion without full incorporation into the domestic sphere. Initially devised by the Navy and embraced by Congress, this system's legal foundation was later solidified by the Supreme Court's "Insular Cases" (1901–1922). Scholars describe this shift as a move "from absorbing new territories into the domestic space of the nation to acquiring foreign colonies and protectorates abroad." In essence, the "Insular Cases" established a hybrid policy, merging elements of U.S. expansionism and colonial governance.[3]

The main cases include:

DeLima v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 1 (1901); Goetze v. United States, 182 U.S. 221 (1901); Armstrong v. United States, 182 U.S. 243 (1901); Downes v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 244 (1901); Huus v. New York & Porto Rico S.S. Co., 182 U.S. 392 (1901); Dooley v. United States, 183 U.S. 151 (1901); Fourteen Diamond Rings v. United States, 183 U.S. 176 (1901); Hawaii v. Mankichi, 190 U.S. 197 (1903); Kepner v. United States, 195 U.S. 100 (1904); Dorr v. United States, 195 U.S. 138 (1904); Rasmussen v. United States, 197 U.S. 516 (1905); Balzac v. Porto Rico, 258 U.S. 298 (1922).

Prior to 1898, the primary distinction between U.S. colonialism and imperialism rested on the intended future of acquired territories. Colonial acquisitions were envisioned as eventual states within the Union, while imperial ventures aimed for temporary domination without statehood aspirations. Following the Spanish-American War and the acquisition of territories like Puerto Rico and the Philippines, the "Insular Cases" (1901–1922) emerged as a unique blend of these approaches. Instead of the clear-cut categories of colonialism and imperialism, the Insular Cases established a hybrid policy incorporating elements of both. This new framework maintained U.S. sovereignty over the territories but denied them the path to statehood, marking a departure from prior colonial practices.[3] It has been since been used to rule all territories acquired after 1898, including Samoa.

The Supreme Court's Insular Cases, decided between 1901 and 1922, established a critical precedent: birth in unincorporated U.S. territories wouldn't automatically grant birthright citizenship. This meant Congress held the power to determine whether inhabitants of those territories received citizenship or not.[3]

Following the initial Insular Cases decisions, Congress responded by classifying residents of all unincorporated territories as "non-citizen nationals." However, the citizenship status of these territories later evolved through various legislative actions. While other territories eventually gained different forms of U.S. citizenship, individuals born in American Samoa currently remain classified as "non-citizen nationals" at birth, lacking automatic U.S. citizenship.[3]

In essence, the Insular Cases rulings severed the automatic link between birth in a U.S. territory and citizenship after 1898. Instead, Congress assumed the authority to grant or withhold citizenship for residents of newly acquired territories.[3]

Current status of the territory and attempts of incorporation into the United States[edit]

After the war, Organic Act 4500, a U.S. Department of Interior-sponsored attempt to incorporate American Samoa, was defeated in Congress, primarily through the efforts of American Samoan chiefs, led by Tuiasosopo Mariota. These chiefs' efforts led to the creation of a local legislature, the American Samoa Fono which meets in the village of Fagatogo, the territory's capital.

In time, the Navy-appointed governor was replaced by a locally elected one. Although technically considered "unorganized" in that the U.S. Congress has not passed an Organic Act for the territory, American Samoa is self-governing under a constitution that became effective on July 1, 1967. The U.S. Territory of American Samoa is on the United Nations list of non-self-governing territories.

The islands have been reluctant to separate from the US in any manner. The maritime boundaries of American Samoa with New Zealand (Tokelau, the Cook Islands, and Niue) have been determined in a series of treaties. Maritime boundaries with Tonga and Samoa have yet to be agreed upon.

Economy of American Samoa[edit]

Employment on the island basically falls into three relatively equally sized categories of approximately 5,000 workers each: the public sector, the tuna cannery, and the rest of the private sector. There are only a few federal employees in American Samoa and no active military personnel (there are several Army Reserve units including companies of the famed 100th Infantry Battalion; the overwhelming majority of public sector employees work for the American Samoa Government. The StarKist cannery exports several hundred million dollars worth of canned tuna to the United States.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ E. E. V. Collocott. "Journal of the Polynesian Society: An Experiment In Tongan History, By E. E. V. Collocott, P 166-184". jps.auckland.ac.nz.

- ^ Rigby, Barry (May 1988). "The Origins of American Expansion in Hawaii and Samoa, 1865–1900". The International History Review. 10 (2): 221–237. doi:10.1080/07075332.1988.9640475. ISSN 0707-5332.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dardani, Ross (2021-02-03). "Citizenship in Empire: The Legal History of U.S. Citizenship in American Samoa, 1899-1960". American Journal of Legal History. 60 (3): 328. doi:10.1093/ajlh/njaa013. ISSN 0002-9319.

- ^ a b Go, Julian (2004). Qualitative Sociology (1 ed.). Springer Science and Business Media LLC. p. 51. doi:10.1007/11133.1573-7837.

Further reading[edit]

- Campbell, Charles S. The transformation of American foreign relations, 1865-1900 (1976) pp 72–83, 311–26.

- Gray, John Alexander Clinton. Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and Its United States Naval Administration (United States Naval Institute, 1960).

- Huebner, Thorn. "Vernacular literacy, English as a language of wider communication, and language shift in American Samoa." Journal of Multilingual & Multicultural Development 7.5 (1986): 393–411.

- Kennedy, Paul. The Samoan Tangle: A Study in Anglo-German-American Relations 1878–1900 (1977).

- Pletcher, David M. The Diplomacy of Involvement: American Economic Expansion across the Pacific, 1784-1900 (2001) online.

- Siebold, Dennis J. "Delaware and the Key to the Pacific: Thomas F. Bayard, George H. Bates, and the Acquisition of American Samoa, 1886--1899" Delaware History (2008) 32#2 pp 105–148. online at Ebsco.