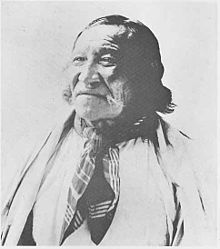

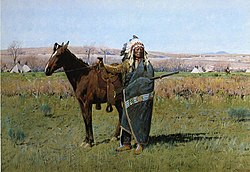

| Chief Crow Dog | |

|---|---|

| Brulé, Lakota | |

| |

| Born | c. 1833 Horse Stealing Creek |

| Died | August 1912 (aged 78–79)[1] Rosebud Indian Reservation, South Dakota, United States |

| Spouse | Catches Her Jumping Elk |

Crow Dog (also Kȟaŋǧí Šúŋka, Jerome Crow Dog; c. 1833 – August 1912) was a Brulé Lakota subchief, born at Horse Stealing Creek, Montana Territory.

Family[edit]

He was the nephew of former principal chief Conquering Bear, who was killed in 1854 in an incident which would be known as the Grattan massacre. He was the great-grandfather of Leonard Crow Dog (1942–2021), a practitioner of traditional herbal medicine, a leader of Sun Dance ceremonies, and preserver of Lakota traditions.

Life[edit]

Crow Dog was a traditionalist and one of the leaders who helped popularize the Ghost Dance. After receiving a vision, Jerome warned several dancers to stay away from a large gathering of tribes in 1890 thus saving them from being victims of the Wounded Knee Massacre.

Murder trial[edit]

On August 5, 1881, after a long-simmering feud, Crow Dog shot and killed principal chief Spotted Tail (who was also at the Grattan massacre), on the Rosebud Indian Reservation. A grand jury was convened and he was tried and convicted in Dakota Territorial court in Deadwood, South Dakota, and sentenced to death which was to be carried out on January 14, 1884. He was imprisoned in Deadwood pending the outcome of his appeals. According to historian Dee Brown in his bestselling book, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee:

White officials... dismissed the killing as the culmination of a quarrel over a woman, but Spotted Tail's friends said that it was the result of a plot to break the power of the chiefs...[2]

In 1883, writs of habeas corpus and certiorari were filed on his behalf by lawyers who volunteered to represent him pro bono; his case was argued in November 1883 before the U.S. Supreme Court in Ex parte Crow Dog. On December 17, 1883, the court ruled in a unanimous decision that according to the provisions of the Treaty of Fort Laramie, signed on April 29, 1868, and approved by Congress on February 28, 1877, the Dakota Territorial court had no jurisdiction over the Rosebud reservation and subsequently overturned his conviction.[3][4] This ruling cited a previous Supreme Court ruling in Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515 (1832), a case brought by the Cherokee tribe against the state of Georgia, in which the court ruled that Native Americans were entitled to federal protection from the actions of state governments which would infringe on the tribe's sovereignty.

Major Crimes Act[edit]

In response to the ruling in Ex parte Crow Dog, the U.S. Congress passed the Major Crimes Act (18 U.S.C. § 1153) in 1885. It places 15 major crimes under federal jurisdiction if they occur on Native territory, even if both perpetrator and victim are Native American, beginning a legal doctrine limiting tribal sovereignty.

Later life[edit]

Crow Dog returned to the Rosebud Indian Reservation, where he remained for the rest of his life. He died there in August 1912.[5]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Wishart, David J. (2004). Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. U of Nebraska Press. p. 451. ISBN 0-8032-4787-7.

- ^ Brown, Dee (1970), Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, Bantam Books, ISBN 0-553-11979-6

- ^ Harring, Sidney L. (1994). Crow Dog's Case: American Indian Sovereignty, Tribal Law, and United States Law in the Nineteenth Century. Studies in North American Indian History. Cambridge University Press. p. 107. ISBN 0-521-46715-2.

- ^ Bailey, Frankie Y.; Chermak, Steven M. (2004). Famous American Crimes and Trials: 1860–1912. Praeger. pp. 101–105. ISBN 0-275-98335-8.

- ^ "Death of Crow Dog". Sioux City Journal. Sioux Falls, South Dakota. 1912-09-01. p. 6. Retrieved 2020-06-12 – via Newspapers.com.