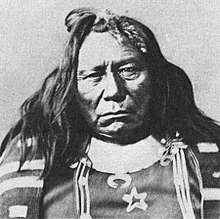

Colorow was a Ute chief of the Ute Mountain Utes, skilled horseman, and warrior. He was involved in treaty negotiations with the U.S. government. In 1879, he fought during the Meeker Massacre. Eight years later, his family members were attacked during Colorow's War.[1] He was placed in the Jefferson County Hall of Fame in recognition of for the contributions that "he made to our county and, indeed, our state and nation."[2]

Early life[edit]

Colorow was born a Comanche about 1810. Five years later there was a battle in Northern New Mexico which resulted in him being kidnapped by the Muache band of Utes. He received the nickname "Red" or "Colorado" for his particularly red skin, as compared to the Utes.[1] His name is spelled with a 'w' at the end, which is a reflection of english language speakers who would have heard the Spanish pronunciation of his name, "Colorao", which is a regional accent in Colorado and New Mexico Spanish where the 'd' in an 'ado' ending word is often softened or dropped, thus, Colorado would be spoken as Colorao, which to a non-Spanish speaker would sound like Colorow.[3]

Career[edit]

Colorow was a skilled horseman and warrior. He traveled across the trails of Colorado, having known many chiefs of other tribes, fur trappers, military men, and the Spanish.[1] He visited Colorado towns.[4] He engaged in battles with the Arapaho, one near Aspen where he was called a hero and another in 1839 against the Arapaho and Cheyenne in the future valley of Golden, Colorado that was so severe that the Utes and plains tribes carefully avoided the valley, making it effectively a Demilitarized zone.[5] In the 1840s he thought to surprise Black Kettle and his band he found camped at a spring where the Golden Mill stands today (1012 Ford Street) in the valley, but was thwarted when Black Kettle made an overnight tactical withdrawal to the top of North Table Mountain to be found the next morning upon the rim with his men shaking their blankets at Colorow in defiance.[6] In 1856, a band of Arapaho and Cheyenne stole about 40 Ute horses. With Nevava and Ouray, Colorow fought for the stolen horses and although outnumbered eight-to-one were able to retrieve them and killed four of the enemy.[1]

Colorow traveled with the band and more than 1,000 horses and goats to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains near present-day Denver. A camp was first established on Lookout Mountain until fresh pastures were required. They then moved to Rooney Valley, east of Dinosaur Ridge near Morrison. They stayed near mineral springs, called "Iron Spring". Other Native American tribes—Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Companche—visited the springs, but the visits were always peaceful there. Colorow held tribal councils at "Inspirational Tree" or "Council Tree" at the foot of Dinosaur Ridge.[1][7] He used a cave near Morrison for temporary shelter, which was named for him, Colorow's Cave.[4] The town of Mount Vernon was built in the area in 1860, and Rooney Ranch that was built in their grazing area.[1] The Ute and Colorow had friendly relations with the Rooney family as they kept their word to them and the other tribes on letting them continue to use Iron Spring, and at Mt. Vernon when friend and mainstay resident William Matthews brought his new wife Frances from far away England on April 20, 1871 the band turned out to see her in what remains a largest recorded wedding reception in Jefferson County history, seen en route through Golden dressed in "rich attire."[8] Colorow and the Ute also had friendly and productive relations with Golden, Colorado, visiting the town seasonally around May and late summer,[9] trading with its merchants,[10] having wrestling and gambling contests with the townspeople including Golden Globe editor Edgar Watson Howe,[11] with Colorow himself dining multiple times with Jefferson County Sheriff W.L. Smith and wife Sophrona,[12] and with family socially visiting with Golden Transcript editor George West.[13] Although West faced Colorow in hostilities later in 1887 as Adjutant General of the Colorado National Guard, West, late in life, told the public he considered Colorow his "more or less esteemed and somewhat obese friend."[14] Lookout Mountain and Indian Gulch at Golden were named because of Colorow, the mountain being a place where he camped, and Indian Gulch was where Colorow came to trade ponies with the townspeople.[15] Colorow also spent part of each summer with his band in the Roaring Fork Valley between Aspen and Gunnison, Colorado.[4]

He was a sub-chief by 1868 and was considered for the chief of the Northern Ute. He was involved in treaty negotiations with the United States government and met with President Ulysses S. Grant at a reception in Denver in 1873. He identified himself as a Yampa and Grand River Ute when he signed the 1878 treaty.[1] During the Meeker Massacre (1879), he first tried to negotiate for peace[1] and ultimately was said to have stabbed Nathan Meeker in the mouth to stop his lies.[4] The conflict led to Utes being put on reservations. Colorow left for the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation in August 1881, and under a treaty he continued to hunt in western Colorado and did not spend much time on the reservation.[1]

In 1887, some minor incidents occurred near Meeker, Colorado, which caused a Rio Blanco County sheriff to establish a posse and hunt down Utes. He burned down Chipeta's camp and injured many of Colorow's family members, include sons, sons-in-law, and grandsons. Utes had begun to return to Utah when a state militia of about 1,000 men began shooting at them. They were rescued by Buffalo Soldiers from Fort Duchesne. The incident, which caused the loss of more than $30,000 (equivalent to $1,017,333 in 2023) in property, was called Colorow's War.[1]

Personal life[edit]

He married three women, who may all have been sisters. His first wife, Recha, gave birth to three of his children Uncompahgre Colorow, Patchoorowits "Gus", and a girl named Topollywack. Recha died when riding a horse; she fell off the horse and her foot was caught in the stirrup and she was dragged to her death. He had six other children with sisters Poopa and Siha by 1857.[1]

He died on the Ouray Reservation on December 11, 1888, and was buried three days later.[1]

Places named for him[edit]

- Colorow's Cave, Morrison, Colorado[4]

- Colorow Elementary School, Jefferson County Public Schools (Colorado)[1]

- Colorow Mountain, Rio Blanco County, Colorado[16]

- Colorow Point Park, Golden, Colorado[1]

- Chief Colorow Park, Littleton, Colorado

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Beth Simmons (February 2016). "Introducing Colorow, a Jefferson County Legend" (PDF). Historoic Jefferson County. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "Colorow" (PDF). Historoic Jefferson County. February 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ Quintero, Blanca (2020-05-25). "Spanish Pronunciation - All about Silent D + Examples". Spanish Pronunciation and Accent Reduction | Blanca Quintero. Retrieved 2024-01-15.

- ^ a b c d e Nelson, Sarah M.; Carillo, Richard F.; Clark, Bonnie J.; Rhodes, Lori E.; Saitta, Dean (January 2, 2009). Denver: An Archaeological History. University Press of Colorado. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-0-87081-984-1.

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". August 21, 1862 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". April 21, 1904 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ "Rooney Ranch". Colorado Encyclopedia. 24 August 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". April 26, 1871 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". August 12, 1929 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". January 16, 1867 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". July 23, 1873 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ "Avalanche-Echo". September 28, 1911 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". May 25, 1870 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". July 27, 1905 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". June 11, 1936 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ Bright, William (2004). Colorado Place Names. Big Earth Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-55566-333-9.