| Battle of Yellow House Canyon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Buffalo Hunters' War, Apache Wars | |||||||

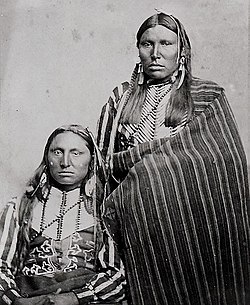

Comanche warriors circa 1870 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Comanche Apache | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Black Horse (Comanche) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 46 militia | ~300 warriors[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

12 killed 8 wounded[1] |

21 killed 22 wounded[1] | ||||||

Location within Texas | |||||||

The Battle of Yellow House Canyon was a battle between a force of Comanches and Apaches against a group of American bison hunters that occurred on March 18, 1877, near the site of the present-day city of Lubbock, Texas. It was the final battle of the Buffalo Hunters' War, and was the last major fight involving the United States and Native Americans on the High Plains of Texas.[2][1]

Background[edit]

The 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty reserved the area between the Arkansas River and the Canadian River as Indian hunting grounds. Yet, since 1873, several buffalo hunting parties operated in the Texas Panhandle, supplied out of Adobe Walls, Texas by Charlie Mayer and Charlie Rath. These incursions already led to the Second Battle of Adobe Walls in 1874.[3]

In December 1876, a group of Comanche under Black Horse received a permit, through the Indian agent at Fort Sill, to allow them to hunt in Texas. But Black Horse had other interests in mind; he was angry that overhunting by settlers had radically thinned herds of American bison (buffalo), and planned to camp in Yellow House Canyon and attack whatever hunters he saw. Earlier in the winter of 1876, buffalo hunter Marshall Sewell had, along with a group of skinners, set up camp below the Caprock in Garza County, near the head of the Salt Fork Brazos River. On February 1, 1877, Sewell discovered a herd of buffalo, and after setting up the station, picked the animals off one-by-one with his rifle before running out of ammunition. Black Horse witnessed this, and with his warriors, surrounded the hunter on his way back to camp. They tortured and double-scalped him before cutting open his stomach and placing pieces of his rifle tripod in the wounds.[1] The action was witnessed by the three skinners who had accompanied Sewell and by another hunter, all of whom were close to a mile away. They hurried to Rath City, the nearest settlement of any size, to report the murder.[3]: 34

Sewell appears to have been popular among local buffalo hunters,[1] and as a result, the reaction came quickly; about 40 men rode to the site of the murder and buried the hunter, after which they picked up the Comanches' trail. The two parties met in a brief skirmish, in which a half-breed hunter named Spotted Jack was wounded by the Texans, who then returned to Rath City. Black Horse took close to 170 warriors, among whom was captive Herman Lehmann, and began plundering hunters' camps in the region. Among those targeted were Pat Garrett and Willis Glenn. Needless to say, the affair caused great consternation among buffalo hunters, and they demanded action be taken.[2]

Battle[edit]

A group of 46 men set out from Rath City on March 4, with the express purpose of finding Black Horse and his men. Jim White was elected captain; a former comanchero from New Mexico, named José, acted as guide. Twenty-six of the men rode horses; the others came by wagon. Two nights into the journey, White began to suffer from bleeding in his lungs, and he was required to turn back to Rath City; one of his lieutenants, Jim Smith, was elevated to captain. The band found the site where Sewell had been captured and there picked up the Comanche's trail, following it westward to just northwest of the present-day city of Post; here, the guide predicted Black Horse and his Comanches would be found in Yellow House Canyon. They did, and they entered the canyon at the site of Buffalo Springs Lake, where they killed a sentry. Scouts sighted the Comanche camp later that same day, and the band began an overnight march to reach it, in the process leaving provisions and wagons at the spring.[2]

The Texans reached the canyon fork, today in Mackenzie State Recreation Area, sometime in the early hours of March 18; for a time, they mistakenly followed the north fork before turning south. Moving west, they found a combined Comanche and Apache camp in Hidden Canyon, a site now marked by Lubbock Lake. By then, much of the day was gone, but the buffalo hunters nevertheless decided to mount an attack. They divided themselves into three groups, two mounted and one not; the mounted men went to the sides of the canyon, on the plain, while the hunters on foot followed the creek in the center. When they were within shooting distance, a charge was ordered. This frightened the natives for a moment, and they started for their horses before discovering how small was the force attacking them. Consequently, they rallied - women ran towards the horsemen discharging pistols, while the warriors set up a defensive position. The spirited defense surprised the Texans, who withdrew. One Joe Jackson was shot in the abdomen; some two months later the wound proved fatal, rendering him one of 12 fatalities on the Texans' side.[1] Several others, including the guide, were wounded, as were a number of natives; most notably among the latter, Herman Lehmann was shot in the thigh, and his companion was killed.[2]

At one point during the fighting, a group of hunters, including John R. Cook, managed to repel a flanking movement from the natives; even so, the outnumbered Texans were forced to withdraw down the canyon. The Comanche then set a grass fire to use it as a smoke screen. At mid-afternoon, a retreat was ordered, and the hunters set out towards Buffalo Springs. The natives trailed them briefly before breaking off. The Texans used a bonfire as a decoy before pulling out altogether during the night; they set fires behind them to obscure their tracks. They finally returned to Rath City on March 27.[2][3]: 35

Aftermath[edit]

Although the battle itself was a failure, it marked the beginning of the end of the war. Word of the fight soon reached Fort Griffin, and Captain P. L. Lee responded by going after the hostiles with 72 soldiers of the 10th Cavalry. At Lubbock Lake, they turned north, and on May 4 overtook the natives at Quemodo Lake in Cochran County. A brief skirmish erupted, in which one Ekawakane and his wife were killed. As a result, the remaining natives surrendered and returned to Fort Sill.[2][3]: 36

By the winter of 1878–1879, the main herd of buffalo on the South Plains had been destroyed, bringing an end to organized buffalo hunting.[3]: 36

Several accounts of the battle exist, told from different points of view. Two of the Texan participants, John Cook and Willis Glenn, left descriptions of the action in their memoirs. Herman Lehmann, too, gave an account of the affair in his autobiography, telling it from the Indian point of view.[2][4]

The site of the battle is today located in the Canyon Lake Project in Lubbock.[2] Monuments mark a number of sites within the area associated with the battle.[1] Some accounts place the frontiersman Charles "Buffalo" Jones, the co-founder of Garden City, Kansas, and a leader in the efforts to prevent the extinction of the buffalo, at the battle site.[5]

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h "LubbockOnline.com - In 1877, Mackenzie Park was site of deadly battle 11/27/07". Archived from the original on 2011-11-03. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Handbook of Texas Online - YELLOW HOUSE CANYON, BATTLE OF

- ^ a b c d e Holden, W.C. (1962). Graves, Lawrence (ed.). Indians, Spaniards, and Anglos, in A History of Lubbock. Lubbock: West Texas Museum Association. pp. 32–33.

- ^ Lehmann, H., 1927, 9 Years Among the Indians, 1870-1879, Austin: Von Beockmann-Jones Company, pp. 171-172

- ^ "Buffalo Jones". h-net.msu.edu. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2010.