| This article is part of a series on |

| Politics of Greece |

|---|

|

Apportionment in the Hellenic Parliament refers to those provisions of the Greek electoral law relating to the distribution of Greece's 300 parliamentary seats to the parliamentary constituencies, as well as to the method of seat allocation in Greek legislative elections for the various political parties. The electoral law was codified for the first time through a 2012 Presidential Decree.[1] Articles 1, 2, and 3 deal with how the parliamentary seats are allocated to the various constituencies, while articles 99 and 100 legislate the method of parliamentary apportionment for political parties in an election.[1] In both cases, Greece uses the largest remainder method.

Up to and including the 2019 Greek legislative election, Greece will continue to employ a semi-proportional representation system with a 50-seat majority bonus. The next election will see the electoral system change to proportional representation, as the majority bonus will cease to be applied since it was abolished in 2016.[2] This article is reflective of this method. The election after next will revert to semi-proportional representation with a sliding scale bonus after it was passed in parliament in 2020.[3]

Background[edit]

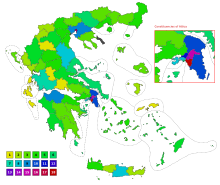

Greek parliamentary constituencies correspond to the former prefectures of Greece with the exception of constituencies in Thessaloniki and Attica,[4] which are divided into two and eight constituencies respectively. Constituencies have generic names, with constituencies which are broken up receiving Greek numerals to differentiate each other, with Thessaloniki A (Greek: Α' Θεσσαλονίκης) for example translating to "first (electoral district) of Thessaloniki". The break-up of Athens B introduced Arabic numerals to the names as well, for example Athens B1 (Greek: Β1' Αθηνών).

As of December 2018, Greece is divided into 59 electoral constituencies of varying sizes.[5] The smallest constituencies are single-seat, while the largest, Athens B3, is represented by 18 members of parliament.[5] Prior to the 2018 reform, which saw Athens B broken up into three smaller constituencies (Athens B1, Athens B2, and Athens B3), Athens B was the largest constituency in the country with 44 MPs, dwarfing the second-largest constituency of Thessaloniki A with 16 MPs.[6]

The Constitution of Greece includes provisions relating both to the constituencies and the number of MPs. Article 51 sets the minimum number of MPs at 200 and the maximum at 300,[7] while Article 53 regulates the way in which constituencies and the electoral law can be changed, while also specifying that up to one twentieth of the total number of MPs (5%, or between 10 and 15 depending on the size of the parliament) may be elected on a national level instead of in constituencies.[8] 12 MPs (4%, or one twenty-fifth) are elected in this manner.

Proportional representation (PR) was first introduced in Greece in the 1926 election, replacing the older approval voting system in use since 1864.[9] Under that system, voters cast lead ballots in ballot boxes corresponding to the number of candidates running in a constituency, placing their lead ballot in the white partition for approval and the black partition for disapproval;[9] the candidates with the highest approval counts were selected until all seats were filled.[9] A majoritarian system was later adopted, with voters voting on party lists and the candidates with the most votes (even if below 50%) being elected.[9] The introduction of PR created unstable governments and it has been re-established a number of times since, most recently in 1989, before being abolished.[10] Reinforced proportional representation favouring the largest party, the type of electoral system used now,[4] was first used in 1951.[10] Overall, Greece has changed its electoral law regarding apportionment in the parliament on average once every 1.5 elections.[10]

The majority bonus was introduced in 2004 to replace the older method of reinforcing the proportional system. Under the previous system, seats were awarded in two or three stages, with increasing quota requirements for each stage.[11][12] In its explanatory report regarding the law, the Hellenic Parliament committee responsible for that piece of legislation concluded that reinforcing the proportional system through a simple majority bonus would significantly lower the malapportionment factor of Greek elections, since it would ensure that all seats are awarded completely proportionally with the exception of the winning party, which would receive a boost equal to 13.33% of the total seats.[13] In particular, political parties would at a minimum be awarded at least 87% of the seats they would be entitled to if the system was not reinforced, as opposed to 70% under the previous law.[13] The bonus was increased to 50 seats in 2009 (a boost of 16.66%), and this was first applied in the May 2012 Greek legislative election.

The majority bonus was abolished in 2016 but was still applied at the 2019 Greek legislative election, with the first elections held after that using proportional representation.[2] As part of the 2019 revision to the Constitution of Greece, the Syriza-led government also wants to enshrine proportional representation in the Constitution.[14] The Constitution would define 'proportional representation' as any system with a margin of error of less than 10% between percentage of the national vote received and percentage of seats awarded, and a maximum electoral threshold of 3% of the national vote.[14] New Democracy, the main opposition party, claimed that proportional representation would result in weak governments like it did in the French Fourth Republic and the Weimar Republic.[14] The 1864 Greek Constitution previously specified approval voting as the official electoral method, until the introduction of proportional representation in 1926;[9] no constitution since then has specified the type of electoral system to be used.

Apportionment of seats allocated to the constituencies[edit]

The number of seats per constituency is calculated by first figuring out the national quota by dividing the total legal population of Greece as recorded in the last census by the number of seats elected in constituencies (285).[15] The integer of the division of the population of each constituency by the national quota, disregarding the decimals (marked in the function below), is the number of seats allocated to that constituency;[16] a constituency with a sum of 5.6 is awarded 5 seats. If there are seats left empty in the first round of allocations, all 59 constituencies are ranked in descending order of leftover decimals () and a seat is awarded to any constituency with a larger than or equal to , where is the number of seats which remained empty in the first allocation;[17] if there are 9 unassigned seats, the constituencies with the 9 highest leftover decimals are awarded a seat each. The mathematical formula below is a summary of this allocation process:

The use of integers only to determine the number of seats in the first allocation means that there are always seats left empty for allocation in the second step, since the number of seats allocated by rounding down is always less than the number of seats a constituency is entitled to. In the 2023 apportionment of seats, 256 seats were awarded to constituencies in the first step and 29 in the second;[5] Evrytania and Lefkada received no seats in the first step, but received one seat each due to their leftover decimals in the second step.[5]

Apportionment of seats allocated to parties in legislative elections[edit]

The first step in determining the result of a Greek legislative election is to find the electoral quota (Greek: εκλογικό μέτρο) of each party on a national level. This is done by taking the number of votes received by each party polling at least 3% nationally and multiplying it by a number as shown in formula, thereupon dividing that sum by the total number of votes cast for political parties which have received at least 3% of the national vote;[18] the number of seats elected in constituencies, without the possible majority bonus. The integer of this calculation gives the number of seats that each party is awarded,[18] in proportion to its electoral result. As with the allocation of seats to the constituencies, if there are any seats left vacant in the first allocation, the political parties are ranked in descending order of leftover decimals () and a seat is awarded to any constituency with a larger than or equal to , where is the number of seats which remained empty in the first allocation.[18] This formula below is a summary of this calculation process:

Because the number of votes is multiplied by a smaller number rather than 300 it ensures that there are always some seats left vacant for the majority bonus. The national quota is used later in order to 'correct' the results in the constituencies, ensuring that the seats of the majority bonus are left vacant as intended. This provision was abolished in 2016, along with the majority bonus, and in elections after 2019 the total number of votes received by a party will be multiplied by 300 instead of 250.[19]

The 15 MPs elected nationally[edit]

In accordance with the constitution, several seats in the parliament are elected on a national level. These MPs are elected through party-list proportional representation using the largest remainder method, with the whole of Greece acting as a single 15-seat constituency. The seats are allocated by first finding the national quota for these 15 seats, dividing the total number of votes cast for all parties which have received at least 3% of the vote nationally by 15, and then dividing the total number of votes for each party which has received at least 3% of the national vote by the national quota for the 15 seats.[20] The integer of this calculation is the number of seats each party is awarded in this apportionment.[20] If there are any seats left vacant in the first allocation, the political parties are ranked in descending order of leftover decimals () and a seat is awarded to any party with a larger than or equal to , where is the number of seats which remained empty in the first allocation.[21] This formula below is a summary of this calculation process:

The 9 MPs elected with First Past the Post[edit]

Nine constituencies of Greece (Cephalonia, Evrytania, Grevena, Kastoria, Kefalonia, Lefkada, Phocis, Samos, and Zakynthos) have only a single MP each.[5] They are mostly islands, and their legal population ranges from 24,545 in Evrytania to 48,464 in Kastoria.[5] Each seat is awarded to the party which has received the most valid votes in each of the single-seat constituencies, provided that that party has received at least 3% of the national vote.[22] This means that if a party is very popular in a single-seat constituency but has not received 3% of the vote nationally, it is disqualified. There is no requirement for a party to reach 50% of the vote before being awarded the seat, as a simple plurality is enough. In this case, the system employed is first-past-the-post or plurality voting.[4]

The MPs who are elected proportionally[edit]

The apportionment of the MPs proportionally-elected in constituencies is by far the most complex step of all the processes, and involves a number of stages. In the first stage, the electoral quota of each constituency is calculated by dividing the total number of votes cast for all parties in the constituency (regardless of if they achieved 3% of the national vote) and dividing it by the number of seats in that constituency.[23] The total number of votes cast for each party in the constituency is then divided by the constituency quota, and the integer of that calculation corresponds to the number of seats awarded to that party,[23] so that a sum of 5.6 would award 5 seats. Any parties which have received more seats than they have candidates are awarded the same number of seats as their number of fielded candidates.[22]

To fill any seats left empty after the first stage, the difference in seats each party is entitled to in accordance with the national quota established before the apportionment of seats began minus the total number of seats that have been awarded to each party so far is calculated.[24] The number of 'unused votes' for each party in the constituency is then calculated, by multiplying the number of seats it has been awarded in the constituency, times the electoral quota established for that constituency.[24] Empty seats in two- and three-member constituencies are awarded, in order and one by one, to the parties which have the highest number of unused votes in that constituency.[25] If any party has been awarded more seats so far than it is entitled to in accordance with the national quota, one seat is removed from it in three-member (and if necessary two-member) constituencies, until it has the same number of allocated seats as it is entitled to.[25]

If there are still constituencies with empty seats, all constituencies with empty seats are ranked in descending order of the unused votes of the political party with the smallest number of valid votes on a national level (that has secured at least 3% of the national vote), and one seat is awarded to that party in those constituencies where it is showing the highest number of unused votes, until that party has reached the number of seats it is entitled to in accordance with the national quota.[26] If there are still seats left empty, this procedure is followed for all other parties in ascending order of total valid votes (that have secured at least 3% of the national vote) until all seats have been allocated.[26]

The seats of the majority bonus[edit]

The seats of the majority bonus can either be awarded to party which has achieved a plurality of votes or to an electoral coalition provided that the average percentage of votes received by the members of the coalition is larger than the percentage of votes received by the political party which has a plurality of votes on a national level.[27] The judgement on whether an organisation is a political party or a political coalition rests with the Supreme Civil and Criminal Court of Greece.[28] If, in exceptional circumstances, the electoral arithmetic results in a situation where the largest party is awarded more seats than there are seats available including the bonus, as a result of the re-allocation of empty seats in the constituencies, then the majority bonus can be reduced so that the largest party can keep the seats awarded to it in the constituencies.[29]

Malapportionment[edit]

The Gallagher index (or Least Squares Index), was developed by Michael Gallagher as a means of measuring the electoral disproportionality or malapportionment between the percentage of votes parties receive in an election versus the percentage of seats allocated to them.[30] Greece's "notorious"[30] 'reinforced proportionality' system produces Gallagher Indices more closely approximating those of first-past-the-post systems rather than proportional systems like Denmark or New Zealand.[31]

Taking the examples of the Gallagher Indices of selected countries in their last election, the September 2015 Greek election had an index of 9.69.[31] The United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada, all first-past-the-post systems, scored 6.47, 11.48, and 12.01 respectively in their last elections (the United Kingdom's Indices prior in the four elections prior to the last one averaged between 15 and 17).[31] France's two-round system produced an index of 21.12, while Denmark and New Zealand, using proportional representation and mixed-member proportional representation, scored 0.79 and 2.73.[31] Greece used proportional representation in the legislative elections of June 1989, November 1989, and 1990, which had lower Gallagher Indices of 4.37, 3.94, and 3.97.[31] When the majority bonus was raised from 40 seats to 50 in the May 2012 election, the Gallagher Index nearly doubled from 7.29 in 2009 to 12.88.[31]

-

Gallagher Indices of Greece between 1946 and 2015

-

Comparison of Gallagher Indices of Greece (blue) and other countries between 1946 and 2017

-

Number of political parties in the Hellenic Parliament by electoral system between 1910 and 2017

References[edit]

- ^ a b Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012.

- ^ a b Law 4406–ΦΕΚ 113/2016.

- ^ "Parliament votes to change election law | Kathimerini". www.ekathimerini.com. Retrieved 2020-01-25.

- ^ a b c Papakonstantinou, Kalliopi; Katsiras, Leonidas. "Εκλογικό σώμα και εκλογικά συστήματα" [Electoral body and electoral systems]. Πολιτική και Δίκαιο [Politics and Justice] (in Greek). Athens: Organisation for the Publishing of Educational Books.

- ^ a b c d e f Presidential Decree 117–ΦΕΚ 225/2018, Art. 1.

- ^ Presidential Decree 4–ΦΕΚ 10/2013, Art. 1.

- ^ Constitution of Greece, Art. 51.

- ^ Constitution of Greece, Art. 53.

- ^ a b c d e Mavrogordatos, George Th. (1983-01-01). Stillborn Republic: Social Coalitions and Party Strategies in Greece 1922–1936. University of California Press. pp. 351–352.

- ^ a b c Papantoniou, Stavros. "Η πολύ σύνθετη... απλή αναλογική" [The very complex... simple proportional representation]. www.kathimerini.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 2019-03-15.

- ^ Legg, Keith R. (1969). Politics in Modern Greece. Stanford University Press. p. 144. ISBN 9780804707053. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

greece%20reinforced%20proportional.

- ^ "Greece's electoral system" (PDF). Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency. 21 March 1985. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 23, 2017.

- ^ a b Christodoulakis, N.; Skandalidis, K.; Petsalnikos, F.; Katrivesis, V. (22 December 2003). "Εισηγητική έκθεση στο σχέδιο νόμου "Εκλογή βουλευτών"" [Introductory report on the law proposal "election of MPs"] (PDF) (in Greek). Athens: Hellenic Parliament. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007.

- ^ a b c "Έκθεση της επιτροπής αναθεώρησης του Συντάγματος" [Report of the committee for the amendment of the Constitution] (PDF) (in Greek). Hellenic Parliament. pp. 13–89. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2019.

- ^ Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 2 §1–3.

- ^ Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 2 §4.

- ^ Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 2 §5.

- ^ a b c Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 99 §1–2.

- ^ Law 4406–ΦΕΚ 113/2016, Art. 2 §1.

- ^ a b Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 100 §1–2.

- ^ Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 100 §3.

- ^ a b Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 100 §5.

- ^ a b Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 100 §4.

- ^ a b Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 100 §6.

- ^ a b Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 100 §7.

- ^ a b Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 100 §8.

- ^ Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 99 §3α.

- ^ Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 99 §3β.

- ^ Law 4255–ΦΕΚ 57/2012, Art. 99 §4.

- ^ a b Gallagher, Michael (1991). "Proportionality, Disproportionality, and Electoral Systems" (PDF). Electoral Studies. 10 (1): 33–51. doi:10.1016/0261-3794(91)90004-c. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 November 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Gallagher, Michael; Mitchell, Paul (2008). Election indices (PDF). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

Sources[edit]

- The Constitution of Greece (PDF), Athens: Hellenic Parliament, 27 May 2008, retrieved 14 March 2019

- Εφημερίδα της Κυβερνήσεως τη Ελληνικής Δημοκρατίας [Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic] (in Greek), vol. A, Athens: National Publishing House, 15 March 2012, retrieved 11 March 2019

- Εφημερίδα της Κυβερνήσεως τη Ελληνικής Δημοκρατίας [Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic] (in Greek), vol. A, Athens: National Publishing House, 14 January 2013, retrieved 13 March 2019

- Εφημερίδα της Κυβερνήσεως τη Ελληνικής Δημοκρατίας [Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic] (in Greek), vol. A, Athens: National Publishing House, 27 July 2016, retrieved 12 February 2019

- Εφημερίδα της Κυβερνήσεως τη Ελληνικής Δημοκρατίας [Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic] (in Greek), vol. A, Athens: National Publishing House, 31 December 2018, retrieved 12 February 2019