Aghasi Khanjian | |

|---|---|

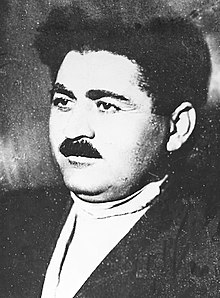

Khanjian in 1934 | |

| First Secretary of the Communist Party of Armenia | |

| In office May 1930 – July 9, 1936 | |

| Preceded by | Haykaz Kostanyan |

| Succeeded by | Amatuni Vardapetyan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 30, 1901 Van, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | July 9, 1936 (aged 35) Tbilisi, Georgian SSR, Transcaucasian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Political party | Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (1919–1936) |

Aghasi Ghevondi Khanjian (Armenian: Աղասի Ղևոնդի Խանջյան; Russian: Агаси Гевондович Ханджян, romanized: Agasi Gevondovich Khandzhyan; January 30, 1901 – July 9, 1936) was First Secretary of the Communist Party of Armenia from May 1930 to July 1936.[1]

Biography[edit]

Khanjian was born in the city of Van, Ottoman Empire (today eastern Turkey).[2] With the onslaught of the Armenian genocide, his family emigrated from the city in 1915 and settled in Russian Armenia, where they took refuge at Etchmiadzin Cathedral.[3] Khanjian enrolled at the Gevorgian Seminary, but gradually became attracted by revolutionary Marxist politics.[3] In 1917–19, he was one of the organizers of Spartak, the Marxist students' union of Armenia. He later served as the secretary of the Armenian Bolshevik underground committee.[4] He was arrested by the Armenian authorities in August 1919.[5] In September 1919, Khanjian was elected in absentia to the Transcaucasian regional committee of Komsomol.[5] He was released from prison by January 1920, but was arrested again on August 1920 and sentenced to ten years of imprisonment.[5] He was released after the establishment of Soviet rule in Armenia in December 1920 and was elected secretary of the Yerevan committee of the Armenian Communist Party, a position he held until February 1921.[5]

Khanjian enrolled in Sverdlov Communist University in Moscow in 1921.[5] After graduating, he worked as a party official in Leningrad, where he supported Joseph Stalin against the city’s party boss, Grigory Zinoviev.[2][4] He was also a close associate of Sergei Kirov.[3] Khanjian returned to Armenia in April 1928 and served as a secretary of the Armenian Communist Party in 1928–29 and first secretary of the Yerevan City Committee of the Communist Party of Armenia in March 1929–May 1930. In May 1930, at the age of 29, he was appointed First Secretary of the Armenian Communist Party.[4] Khanjian was opposed by the old Armenian Bolsheviks who had ruled Armenia since the early 20s, but he was gradually able to sideline them.[2] Khanjian's rival in the Armenian Communist Party was Sahak Ter-Gabrielyan, who was Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Armenian SSR from 1928 to 1935.[6]

Khanjian took over the leadership of the Armenian party at a time when the peasants were being forced to give up their land and were being driven onto collective farms, on instructions in Moscow. This provoked widespread resistance. The Soviet press revealed at the time that the communists lost control of parts of Armenia, which were in rebel hands for several weeks in March and April 1930.[7] Under Khanjian, the process was completed without any reports of armed clashes between rebels and the security services. A more lenient collectivization policy was adopted in 1930, and many forcibly created collective farms were dissolved.[8] Instead, the government imposed high taxes on private farms in order to push peasants to join collective farms.[8] By 1932, around 40 percent of the Armenian republic's peasants had joined collective farms.[8] Khanjian proved to be a charismatic Soviet politician and was very popular among the Armenian populace.[1]

Politically, Khanjian was "as much of a nationalist as a Communist could safely be at the time – and probably a little more so."[3] He was a friend and supporter of many Armenian intellectuals, including Yeghishe Charents (who dedicated a poem to him), Axel Bakunts and Gurgen Mahari (all three were subjected to political repressions after Khanjian's death).[4] In a speech in January 1932, Khanjian condemned “Great Russian chauvinism” and defended the Armenian language, literature, and history.[2] Two years later, in following with the shift in Stalinist policy toward condemning local nationalism, Khanjian fiercely criticized Armenian nationalism and alleged that it was still widespread among Armenian intellectuals.[2] In a 1935 letter addressed to Stalin criticizing Khanjian, Armenian Bolshevik Aramayis Yerznkyan cited Khanjian's support for the unification of Kars, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Nakhijevan with Soviet Armenia as evidence of the latter's "nationalism."[9] Khanjian paid particular attention to encouraging immigration Soviet Armenia from the Armenian diaspora and to the republic's links with diasporic organizations.[5] In October 1931, Khanjian gave a speech condemning Calouste Gulbenkian, the wealthy British-Armenian businessman and president of the Armenian General Benevolent Union, which contributed to Gulbenkian's resignation from the post in 1932.[6]

Conflict with Beria and death[edit]

In the mid-1930s, Khanjian came into conflict with Lavrentiy Beria, the leader of the Georgian SSR and the most powerful party leader in the Transcaucasian SFSR.[10][11] Khanjian had poor relations with Beria and had openly opposed Stalin's decision to promote Beria to the post of second secretary of the Transcaucasian party regional committee in 1931 (Beria became first secretary the following year).[9][11] Khanjian was targeted by Beria as a leader with his own power base and an obstacle to Beria's consolidation of power over the Transcaucasian republics.[11][12] Beria replaced many of Khanjian's allies in Armenia with his own in the lead-up to Khanjian's death.[9] Beria was also motivated to replace Khanjian with one of his loyalists by the planned dissolution of the Transcaucasian SFSR in 1937, which would leave Beria with less power over the Transcaucasian republics besides Georgia.[11] Khanjian's attempts to secure as much autonomy as possible for Armenia under the new Soviet constitution further antagonized Beria.[11]

On May 21, 1936, the NKVD arrested Nersik Stepanyan, the director of the Institute of Marxism-Leninism in Armenia, as a “counterrevolutionary nationalist-Trotskyite.”[12] On July 9, Beria called a meeting of the Transcaucasian party bureau in Tbilisi, where he and his allies accused Khanjian of protecting Stepanyan.[12] Around 5:30 p.m., Khanjian went to his apartment in Tbilisi. He was found in his room by his bodyguards with a bullet wound to the head between 7:00 and 8:00 p.m.[12] He was transported to a Tbilisi hospital and operated upon around 1:30 a.m., but was pronounced dead. His death date was recorded as July 9.[12]

Political condemnations of Khanjian came soon after his death. On July 11, 1936, the newspaper Zarya Vostoka declared that Khanjian had committed suicide, calling it “a manifestation of cowardice especially unworthy of a leader of a party organization.”[12] It was alleged that Khanjian had “committed errors, demonstrating insufficient vigilance in the case of the discovery of nationalist, counterrevolutionary, and Trotskyite groups,” and that he committed suicide because he "could not find the courage within himself to correct [his mistakes] in a Bolshevik manner."[11][12] On July 20, 1936, Beria published an article in where he accused Khanjian of patronizing "rabid nationalist elements among the Armenian intelligentsia" and "abetting the terrorist group of Stepanyan".[13] Khanjyan was buried in Yerevan without public ceremony.[12] By December 1936, the narrative of Khanjian's suicide was publicly endorsed by Stalin and the USSR's most prominent Armenian politician, Anastas Mikoyan.[14]

Soon after Khanjian's death, Beria promoted his loyalists Amatuni Amatuni as Armenian First Secretary and Khachik Mughdusi as chief of the Armenian NKVD.[15] According to Amatuni in a June 1937 letter to Stalin, 1,365 people were arrested in the ten months after the death of Khanjian, among them 900 "Dashnak-Trotskyists" (Amatuni himself was later arrested in 1937 and shot in 1938).[13] Along with an entire generation of intellectual Armenian communist leaders, Khanjian was denounced as an "enemy of the people" during Stalin's Great Purge.[1]

Khanjian's personal friend Yeghishe Charents wrote a series of seven sonnets dedicated to him after his death, titled Dofinë nairakan: yot’ sonet Aghasi Khanjyanin (The dauphin of Nairi: seven sonnets to Aghasi Khanjian).[9] Charents was arrested and died in prison in November 1937. On 11 March 1954, in a speech in Yerevan, Mikoyan called for the rehabilitation of Charents, beginning the process of the Thaw in Armenia.[15] Khanjian was officially rehabilitated by Soviet authorities in 1956, two years after Mikoyan's speech and three years after the death of Stalin and the arrest and execution of Beria. An official Soviet investigation concluded that same year that Beria had shot Khanjian dead in his office.[16] In October 1961, KGB Chairman Alexander Shelepin publicly referred to that conclusion at the 22nd Congress of the Soviet Communist Party.[17] Historian Stephen Kotkin considers it unlikely that Beria would have shot Khanjian in his own office when members of the Moscow party Control Commission were in an adjacent room, noting that "The relentless hounding and arrest preparations by Beria’s henchmen were enough to drive someone to shoot himself."[12]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Matossian, Mary Kilbourne (1975). "Armenia and the Armenians". In Katz, Zev; Rogers, Rosemarie; Harned, Frederic (eds.). Handbook of Major Soviet Nationalities. New York: Free Press. pp. 146–147. ISBN 9780029170908.

- ^ a b c d e Suny, Ronald Grigor (1993). Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History. Indiana University Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0253207739.

- ^ a b c d Matossian, Mary Kilbourne (1962). The Impact of Soviet Policies in Armenia. Leiden: E.J. Brill. pp. 119–122.

- ^ a b c d Ханджян Агаси Гевондович in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 1969–1978 (in Russian)

- ^ a b c d e f Mnatsakanian, A. (1979). "Khanjyan Aghasi Ghevondi" Խանջյան Աղասի Ղևոնդի. In Arzumanian, Makich (ed.). Haykakan sovetakan hanragitaran Հայկական սովետական հանրագիտարան [Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia] (in Armenian). Vol. 5. Yerevan. pp. 13–14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Tachjian, Vahé (2020). "Humanitarian diaspora? The AGBU in Soviet Armenia, 1920–1930s". In Piana, Francesca; Laycock, Joanne (eds.). Aid to Armenia: Humanitarianism and Intervention from the 1890s to the Present. Manchester University Press. p. 125. ISBN 9781526142221.

- ^ Conquest, Robert (1988). The Harvest of Sorrow, Soviet Collectivisation and the Terror-Famine. London: Arrow. p. 156. ISBN 0-09-956960-4.

- ^ a b c Geghamyan, G․ M․; et al. (2012). "Khorhrdayin Hayastaně 1920-1945 tʻvakannerin" Խորհրդային Հայաստանը 1920-1945 թվականներին [Soviet Armenia 1920-1945]. In Simonyan, H․ Ṙ․ (ed.). Hayotsʻ patmutʻyun: Hnaguyn zhamanakneritsʻ minchʻev mer ōrerě Հայոց պատմություն․ Հնագույն ժամանակներից մինչև մեր օրերը (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Yerevan State University Publishing House. p. 640.

- ^ a b c d Gyulmisaryan, Ruben (July 9, 2021). "Mi spanutʻyan patmutʻyun. Aghasi Khanjyan, 9 hulisi, 1936tʻ, Tʻiflis" Մի սպանության պատմություն. Աղասի Խանջյան, 9 հուլիսի, 1936թ, Թիֆլիս [History of a murder: Aghasi Khanjian, 9 July, 1936, Tiflis]. ANI Armenian Research Center (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (1997). "Soviet Armenia". In Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.). The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century. New York: St Martin's Press. p. 362. ISBN 0-333-61974-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Knight, Amy (1993). Beria: Stalin's First Lieutenant. Princeton University Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 0-691-03257-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kotkin, Stephen (2017). Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929–1941. New York: Penguin Press. pp. 690–691. ISBN 9780735224483.

Some Caucasus officials, as well as Armenian émigrés, many of whom viewed Khanjyan as a patriot, suspected that Beria, in his own office, had shot him in cold blood. But a visiting Moscow party Control Commission sat in the very next room and would have been able to hear and then observe such an incident. In fact, Khanjyan left suicide notes, at least one of which his wife accepted as her husband's handwriting. Beria was unscrupulous, but more calculating than impulsive. Khanjyan's removal as party boss of Armenia, in any case, was imminent. The relentless hounding and arrest preparations by Beria's henchmen were enough to drive someone to shoot himself.

- ^ a b Barseghyan, Artak R. (July 9, 2021). "Kto ubil Agasi Khandzhiana?" Кто убил Агаси Ханджяна? [Who killed Aghasi Khanjian?]. armradio.am (in Russian). Public Radio of Armenia. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Getty, J. Arch; Naumov, Oleg V. (1999). The Road to Terror: Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932-1939. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 322. ISBN 0-300-07772-6.

- ^ a b Shakarian, Pietro A. (12 November 2021). "Yerevan 1954: Anastas Mikoyan and Nationality Reform in the Thaw, 1954–1964". Peripheral Histories. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Artizov, A. N.; Sigachev, Yu. V.; Khlopov, V. G.; Shevchuk, I. N., eds. (2000). Reabilitatsiia: kak ėto bylo. Dokumenty Prezidiuma TSK KPSS i drugie materialy. Tom 1. Mart 1953 — fevralʹ 1956 Реабилитация: как это было. Документы Президиума ЦК КПСС и другие материалы. Том 1. Март 1953 — февраль 1956 [Rehabilitation: how it happened: documents of the Presidium of the CPSU Central Committee and other materials, Volume 1, March 1953-February 1956] (in Russian). Moscow: МФД. pp. 314–316. ISBN 5-85646-070-7.

- ^ Medvedev, Roy Aleksandrovich (1989). Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism. Translated by Shriver, George. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 413. ISBN 9780231063500.