Thomas J. Mastin | |

|---|---|

| Born | September 13, 1839 Aberdeen, Mississippi |

| Died | October 7, 1861 (aged 22) Confederate Arizona |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | Arizona Guards |

| Battles/wars | |

Thomas J. Mastin[a] (September 13, 1839 — October 7, 1861) was a Confederate captain, attorney, and businessman. He founded the Arizona Guards, who fought as a part of the Confederate Army in the American Civil War and the Apache Wars.

Biography[edit]

On September 13, 1839, Mastin was born as the fourth of nine children had by Reuben Frasier and Letita Minerva Mastin née Browne in Aberdeen, Mississippi. Reuben collected mulberries, but in September 1841, sold his property and moved the family to Pontotoc, becoming a blacksmith. In 1849, Frasier and his eldest son John went to capitalize on the California Gold Rush, with John dying near the Great Salt Lake from cholera and Frasier completing the trip. Mastin's grandpa in South Carolina, Reuben, deeded Letita 160 acres of land in Pontotoc County during this time. On September 19, 1850, Frasier was reported as back with his wife and seven children, a blacksmith owning $1,000 in real estate, and owning two slaves. That year six of the children, including Mastin, attended school. Frasier returned to California thereafter and in 1857, his family settled with him in Quincy.[1]

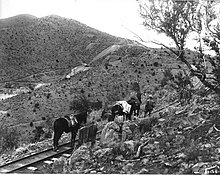

In 1858, Mastin moved to Gila City, New Mexico Territory, where he worked as an attorney. In 1860, he was elected as the city's delegate to the constitutional assembly held in Tucson from April 2 to 5. The result was the promulgation of the provisional Arizona Territory, with Lewis S. Owings as governor. Owings appointed Mastin attorney general of Castle Dome County (within modern-day Yuma County). On August 15, 1860, the census listed him as an unmarried merchant with $2,000 in real estate and $6,500 in personal property; at that point he also operated a mining business in Piños Altos, Doña Ana County, where gold was discovered in May.[b] Still practicing law, in December, he discovered a quartz lode along the Continental Divide near Piños Altos,[4] naming it the Pacific. He also found a second, which he named the Atlantic.[3] In 1861, he co-owned a ranch with Thomas Jefferson Helm. Gaining local popularity, The Mesilla Times titled him "colonel".[4] It also reported him as practicing law in Mesilla County, with his office in Piños Altos, and in the Supreme Court of the Territory of Arizona on February 16, 1861;[5] such was reiterated on March 2.[6] On March 16, Mastin, representative of Piños Altos, voted in a convention in Mesilla to form Confederate Arizona.[4] On May 15, Mastin was shot by John Portell in Mesilla, with a bounty for $200 being posted the next day.[7] On July 18, Mastin formed the Arizona Guards, and on August 1, Arizona seceded under Governor John R. Baylor; the Arizona Guards entered the Confederate Army, being stationed for 12 months at Fort Fillmore.[4]

The guards mostly scouted and engaged the Apache, pursuing as far as Lake Guzmán, Second Federal Republic of Mexico. However, on September 27, his brachial artery was severely wounded during the Battle of Pinos Altos while repelling 250–300 Apaches;[8] he died of blood poisoning on October 7.[9] The following day, the guards and the citizens of Piños Altos held a funeral, in which they decided to bear a medal on his left arm for 30 days. Lieutenant Helm was elected as his successor.[10] Mastin was buried in the Piños Altos cemetery, with his marker reading "Marston".[11]

In 1866, during a second gold rush in Piños Altos, Virgil Mastin constructed a 15-stamp mill for the Atlantic. By the time the Piños Altos mines were abandoned in the 1870s, the area had produced nearly $3,000,000 worth of gold over thirty years.[12]

Sources[edit]

- Notes

- ^ Occasionally erroneously written as "Marston".

- ^ Darlis A. Miller claims Mastin discovered the gold instead of "Thomas Marston" as asserted in Philip Varney's New Mexico's Best Ghost Towns: A Practical Guide (1981).[2] Frank D. Reeve credits prospectors Hicks, Birch, and Snively, whom informed Santa Rita-based Mastin.[3]

- Citations

- ^ Hall 1974, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Miller, Darlis A. (1989). "Review of NEW MEXICO'S BEST GHOST TOWNS: A Practical Guide". Southern California Quarterly. 71 (4): 368. doi:10.2307/41171464. ISSN 0038-3929. JSTOR 41171464.

- ^ a b Reeve 1961, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Hall 1974, p. 144.

- ^ "Thomas J. Mastin". Mesilla Times. Vol. 1, no. 19. Mesilla: Newspaper.com. February 23, 1861. p. 1.

- ^ "Thomas J. Mastin". Mesilla Times. Vol. 1, no. 20. Mesilla: Newspaper.com. March 2, 1861. p. 1.

- ^ Kühn, Berndt (1997). "SIEGE IN COOKE'S CANYON: The Freeman Thomas Fight of 1861". The Journal of Arizona History. 38 (2): 160. ISSN 0021-9053. JSTOR 41696341.

- ^ Hall 1974, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Allen, R. S. (October 1, 1948). "Pinos Altos, New Mexico". New Mexico Historical Review. 23 (4): 304. ISSN 0028-6206.

- ^ Hall 1974, p. 145.

- ^ Fugate, Francis L. (1989). Roadside history of New Mexico. Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Company. p. 434. ISBN 978-0-87842-248-7.

- ^ Reeve 1961, p. 234.

- Bibliography

- Hall, Martin Hardwick (April 1, 1974). "Captain Thomas J. Mastin's Arizona Guards, C.S.A." New Mexico Historical Review. 49 (2): 143–151. ISSN 0028-6206.

- Reeve, Frank Driver (1961). History of New Mexico, Volume 2. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing.