| Continent | North America |

|---|---|

| Region | Northern America |

| Coordinates | 60°00′N 95°00′W / 60.000°N 95.000°W |

| Area | Ranked 2nd |

| • Total | 9,984,671 km2 (3,855,103 sq mi) |

| • Land | 91.08% |

| • Water | 8.92% |

| Coastline | 202,080 km (125,570 mi) |

| Borders | 8,893 km |

| Highest point | Mount Logan, 5,959 m (19,551 ft) |

| Lowest point | Atlantic Ocean, Sea Level |

| Longest river | Mackenzie River, 4,241 km (2,635 mi) |

| Largest lake | Great Bear Lake 31,153 km2 (12,028 sq mi) |

| Climate | temperate, or humid continental to subarctic or arctic in north, and tundra in mountainous areas, and the far north |

| Terrain | mostly plains and mountains in west, to highlands (low mountains) in the south east, and east, to flatlands in the Great lakes |

| Natural resources | iron ore, nickel, zinc, copper, gold, lead, molybdenum, potash, diamonds, silver, fish, timber, wildlife, coal, petroleum, natural gas, hydropower |

| Natural hazards | permafrost, cyclonic storms, tornadoes, forest fires |

| Environmental issues | air and water pollution, acid rains |

| Exclusive economic zone | 5,599,077 km2 (2,161,816 sq mi) |

Canada has a vast geography that occupies much of the continent of North America, sharing land borders with the contiguous United States to the south and the U.S. state of Alaska to the northwest. Canada stretches from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west; to the north lies the Arctic Ocean.[1] Greenland is to the northeast and to the southeast Canada shares a maritime boundary with France's overseas collectivity of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, the last vestige of New France.[2] By total area (including its waters), Canada is the second-largest country in the world, after Russia. By land area alone, however, Canada ranks fourth, the difference being due to it having the world's largest proportion of fresh water lakes.[3] Of Canada's thirteen provinces and territories, only two are landlocked (Alberta and Saskatchewan) while the other eleven all directly border one of three oceans.

Canada is home to the world's northernmost settlement, Canadian Forces Station Alert, on the northern tip of Ellesmere Island – latitude 82.5°N – which lies 817 kilometres (508 mi) from the North Pole.[4] Much of the Canadian Arctic is covered by ice and permafrost.[5] Canada has the longest coastline in the world, with a total length of 243,042 kilometres (151,019 mi);[6] additionally, its border with the United States is the world's longest land border, stretching 8,891 kilometres (5,525 mi).[7] Three of Canada's Arctic islands, Baffin Island, Victoria Island and Ellesmere Island, are among the ten largest in the world.[8]

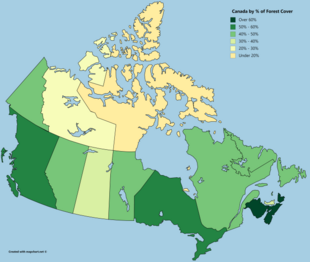

Since the end of the last glacial period, Canada has consisted of eight distinct forest regions, including extensive boreal forest on the Canadian Shield.[9] 42 percent of the land acreage of Canada is covered by forests, approximately 8 percent of the world's forested land, made up mostly of spruce, poplar and pine.[10] Canada has over 2,000,000 lakes—563 greater than 100 km2 (39 sq mi)—which is more than any other country, containing much of the world's fresh water.[11][12] There are also freshwater glaciers in the Canadian Rockies and the Coast Mountains.[13]

Canada is geologically active, having many earthquakes and potentially active volcanoes, notably the Mount Meager massif, Mount Garibaldi, the Mount Cayley massif, and the Mount Edziza volcanic complex.[14] Average winter and summer high temperatures across Canada range from Arctic weather in the north, to hot summers in the southern regions, with four distinct seasons.

Climate

Canada has a diverse climate. The climate varies from temperate on the west coast of British Columbia[15] to a subarctic climate in the north.[16] Extreme northern Canada can have snow for most of the year with a Polar climate.[17] Landlocked areas tend to have a warm summer continental climate zone[18] with the exception of Southwestern Ontario which has a hot summer humid continental climate.[18] Parts of Western Canada have a semi-arid climate, and parts of Vancouver Island can even be classified as a Warm-summer Mediterranean climate.[17] Temperature extremes in Canada range from 45.0 °C (113.0 °F) in Midale and Yellow Grass, Saskatchewan on July 5, 1937 to −63.0 °C (−81.4 °F) in Snag, Yukon on Monday, February 3, 1947.[19]

| City | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calgary[20] | 23/9 | 73/48 | −1/−13 | 27/8 |

| Charlottetown[21] | 23/14 | 78/54 | −3/−13 | 26/9 |

| Edmonton[22] | 23/12 | 73/54 | −6/−15 | 22/13 |

| Fredericton[23] | 26/13 | 78/54 | −4/−16 | 25/4 |

| Halifax[24] | 23/14 | 73/58 | 0/−9 | 32/17 |

| Iqaluit[25] | 12/4 | 53/39 | −23/−31 | −9/−24 |

| Montreal[26] | 26/16 | 79/60 | −5/−12 | 22/6 |

| Ottawa[27] | 27/15 | 80/60 | −6/−15 | 21/5 |

| Quebec City[28] | 25/13 | 77/56 | −8/−18 | 18/0 |

| Regina[29] | 26/11 | 79/52 | −10/−22 | 14/−8 |

| Saskatoon[30] | 25/11 | 77/52 | −12/−22 | 10/−8 |

| St. John's[31] | 20/11 | 69/51 | −1/−9 | 30/17 |

| Toronto[32] | 26/18 | 80/64 | −1/−7 | 30/19 |

| Whitehorse[33] | 21/8 | 70/46 | −11/−20 | 12/−4 |

| Windsor[34] | 28/17 | 82/63 | −1/−8 | 30/17 |

| Winnipeg[35] | 26/13 | 79/55 | −13/−20 | 9/−4 |

| Vancouver[36] | 22/13 | 71/54 | 6/1 | 43/33 |

| Victoria[37] | 22/11 | 71/51 | 7/1 | 44/33 |

| Yellowknife[38] | 21/13 | 70/55 | −22/−30 | −8/−22 |

Physical geography

Canada covers 9,984,670 km2 (3,855,100 sq mi) and a panoply of various geoclimatic regions. There are 8 main regions.[39] Canada also encompasses vast maritime terrain, with the world's longest coastline of 243,042 kilometres (151,019 mi).[40] The physical geography of Canada is widely varied. Boreal forests prevail throughout the country, ice is prominent in northerly Arctic regions and through the Rocky Mountains, and the relatively flat Canadian Prairies in the southwest facilitate productive agriculture.[39] The Great Lakes feed the St. Lawrence River (in the southeast) where lowlands host much of Canada's population.

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian mountain range extends from Alabama through the Gaspé Peninsula and the Atlantic Provinces, creating rolling hills indented by river valleys.[41] It also runs through parts of southern Quebec.[41]

The Appalachian mountains (more specifically the Chic-Choc Mountains, Notre Dame, and Long Range Mountains) are an old and eroded range of mountains, approximately 380 million years in age. Notable mountains in the Appalachians include Mount Jacques-Cartier (Quebec, 1,268 m or 4,160 ft), Mount Carleton (New Brunswick, 817 m or 2,680 ft), The Cabox (Newfoundland, 814 m or 2,671 ft).[42] Parts of the Appalachians are home to a rich endemic flora and fauna and are considered to have been nunataks during the last glaciation era. [43]

Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Lowlands

The southern parts of Quebec and Ontario, in the section of the Great Lakes (bordered entirely by Ontario on the Canadian side) and St. Lawrence basin (often called St. Lawrence Lowlands), is another particularly rich sedimentary plain.[44] Prior to its colonization and heavy urban sprawl of the 20th century, this Eastern Great Lakes lowland forests area was home to large mixed forests covering a mostly flat area of land between the Appalachian Mountains and the Canadian Shield.[45] Most of this forest has been cut down through agriculture and logging operations, but the remaining forests are for the most part heavily protected. In this part of Canada the Gulf of St. Lawrence is one of the world's largest estuary (see Gulf of St. Lawrence lowland forests).[46]

While the relief of these lowlands is particularly flat and regular, a group of batholites known as the Monteregian Hills are spread along a mostly regular line across the area.[47] The most notable are Montreal's Mount Royal and Mont Saint-Hilaire. These hills are known for a great richness in precious minerals.[47]

Canadian Shield

The northeastern part of Alberta, northern parts of Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec, as well as most of Labrador (the mainland portions of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador), are located on a vast rock base known as the Canadian Shield. The Shield mostly consists of eroded hilly terrain and contains many lakes and important rivers used for hydroelectric production, particularly in northern Quebec and Ontario. The shield also encloses an area of wetlands, the Hudson Bay lowlands. Some particular regions of the Shield are referred to as mountain ranges, including the Torngat and Laurentian Mountains.[48]

The Shield cannot support intensive agriculture, although there is subsistence agriculture and small dairy farms in many of the river valleys and around the abundant lakes, particularly in the southern regions. Boreal forest covers much of the shield, with a mix of conifers that provide valuable timber resources in areas such as the Central Canadian Shield forests ecoregion that covers much of Northern Ontario. The region is known for its extensive mineral reserves.[48]

The Canadian Shield is known for its vast minerals, such as emeralds, diamonds and copper. The Canadian shield is also called the mineral house.

Canadian Interior Plains

The Canadian Prairies are part of a vast sedimentary plain covering much of Alberta, southern Saskatchewan, and southwestern Manitoba, as well as much of the region between the Rocky Mountains and the Great Slave and Great Bear lakes in Northwest Territories. The plains generally describes the expanses of (largely flat) arable agricultural land which sustain extensive grain farming operations in the southern part of the provinces. Despite this, some areas such as the Cypress Hills and the Alberta Badlands are quite hilly and the prairie provinces contain large areas of forest such as the Mid-Continental Canadian forests. The size is roughly ~1,900,000 km2 (733,594.1 sq mi).

Western Cordillera

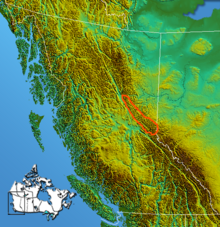

The Canadian Cordillera, contiguous with the American cordillera, is bounded by the Rocky Mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west.

The Canadian Rockies are part of a major continental divide that extends north and south through western North America and western South America. The Columbia and the Fraser Rivers have their headwaters in the Canadian Rockies and are the second and third largest rivers respectively to drain to the west coast of North America. To the west of their headwaters, across the Rocky Mountain Trench, is a second belt of mountains, the Columbia Mountains, comprising the Selkirk, Purcell, Monashee and Cariboo Mountains sub-ranges.

Immediately west of the Columbia Mountains is a large and rugged Interior Plateau, encompassing the Chilcotin and Cariboo regions in central British Columbia (the Fraser Plateau), the Nechako Plateau further north, and also the Thompson Plateau in the south. The Peace River Valley in northeastern British Columbia is Canada's most northerly agricultural region, although it is part of the Prairies. The dry, temperate climate of the Okanagan Valley in south central British Columbia provides ideal conditions for fruit growing and a flourishing wine industry; the semi-arid belt of the Southern Interior also includes the Fraser Canyon, and Thompson, Nicola, Similkameen, Shuswap and Boundary regions and fruit-growing is common in these areas also, and also in the West Kootenay. Between the plateau and the coast is the province's largest mountain range, the Coast Mountains. The Coast Mountains contain some of the largest temperate-latitude icefields in the world.

On the south coast of British Columbia, Vancouver Island is separated from the mainland by the continuous Juan de Fuca, Georgia, and Johnstone Straits. Those straits include a large number of islands, notably the Gulf Islands and Discovery Islands. North, near the Alaskan border, Haida Gwaii lies across Hecate Strait from the North Coast region and to its north, across Dixon Entrance from Southeast Alaska. Other than in the plateau regions of the Interior and its many river valleys, most of British Columbia is coniferous forest. The only temperate rain forests in Canada are found along the Pacific Coast in the Coast Mountains, on Vancouver Island, and on Haida Gwaii, and in the Cariboo Mountains on the eastern flank of the Plateau.

The Western Cordillera continues northwards past the Liard River in northernmost British Columbia to include the Mackenzie and Selwyn Ranges which lie in the far western Northwest Territories and the eastern Yukon Territory. West of them is the large Yukon Plateau and, west of that, the Yukon Ranges and Saint Elias Mountains, which include Canada's and British Columbia's highest summits, Mount Saint Elias in the Kluane region and Mount Fairweather in the Tatshenshini-Alsek region. The headwaters of the Yukon River, the largest and longest of the rivers on the Pacific Slope, lie in northern British Columbia at Atlin and Teslin Lakes.

Volcanoes

Western Canada has many volcanoes and is part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, a system of volcanoes found around the margins of the Pacific Ocean. There are over 200 young volcanic centres that stretch northward from the Cascade Range to Yukon. They are grouped into five volcanic belts with different volcano types and tectonic settings. The Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province was formed by faulting, cracking, rifting, and the interaction between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate. The Garibaldi Volcanic Belt was formed by subduction of the Juan de Fuca Plate beneath the North American Plate. The Anahim Volcanic Belt was formed as a result of the North American Plate sliding westward over the Anahim hotspot. The Chilcotin Group is believed to have formed as a result of back-arc extension behind the Cascadia subduction zone. The Wrangell Volcanic Field formed as a result of subduction of the Pacific Plate beneath the North American Plate at the easternmost end of the Aleutian Trench. The volcanic eruption of the Tseax Cone in 1775 was among Canada's worst natural disasters, killing an estimated 2,000 Nisga'a people and destroying their village in the Nass River valley of northern British Columbia.[49] The eruption produced a 22.5-kilometre (14.0 mi) lava flow, and, according to Nisga'a legend, blocked the flow of the Nass River.[50]

Volcanism has also occurred in the Canadian Shield. It contains over 150 volcanic belts (now deformed and eroded down to nearly flat plains) that range from 600 million to 2.8 billion years old. Many of Canada's major ore deposits are associated with Precambrian volcanoes. There are pillow lavas in the Northwest Territories that are about 2.6 billion years old and are preserved in the Cameron River Volcanic Belt. The pillow lavas in rocks over 2 billion years old in the Canadian Shield signify that great oceanic volcanoes existed during the early stages of the formation of the Earth's crust. Ancient volcanoes play an important role in estimating Canada's mineral potential. Many of the volcanic belts bear ore deposits that are related to the volcanism.

Canadian Arctic

While the largest part of the Canadian Arctic is composed of seemingly endless permafrost and tundra north of the tree line, it encompasses geological regions of varying types: the Arctic Cordillera (with the British Empire Range and the United States Range on Ellesmere Island) contains the northernmost mountain system in the world. The Arctic Lowlands and Hudson Bay lowlands comprise a substantial part of the geographic region often designated as the Canadian Shield (in contrast to the sole geologic area). The ground in the Arctic is mostly composed of permafrost, making construction difficult and often hazardous, and agriculture virtually impossible.

The Arctic, when defined as everything north of the tree line, covers most of Nunavut and the northernmost parts of Northwest Territories, Yukon, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Labrador.

Hydrography

Canada holds vast reserves of water: its rivers discharge nearly 9% of the world's renewable water supply,[51] it contains a quarter of the world's wetlands, and it has the third largest amount of glaciers (after Antarctica and Greenland). Because of extensive glaciation, Canada hosts more than two million lakes: of those that are entirely within Canada, more than 31,000 are between 3 and 100 square kilometres (1.2 and 38.6 sq mi) in area, while 563 are larger than 100 km2 (38.6 sq mi).[52]

Rivers

Canada's two longest rivers are the Mackenzie, which empties into the Arctic Ocean and drains a large part of northwestern Canada, and the St. Lawrence, which drains the Great Lakes and empties into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The Mackenzie is over 4,200 km (2,600 mi) in length while the St. Lawrence is over 3,000 km (1,900 mi) in length. Rounding out the ten longest rivers within Canada are the Nelson, Churchill, Peace, Fraser, North Saskatchewan, Ottawa, Athabasca and Yukon rivers.[53]

Drainage basins

The Atlantic watershed drains the entirety of the Atlantic provinces (parts of the Quebec-Labrador border are fixed at the Atlantic Ocean-Arctic Ocean continental divide), most of inhabited Quebec and large parts of southern Ontario. It is mostly drained by the economically important St. Lawrence River and its tributaries, notably the Saguenay, Manicouagan and Ottawa rivers. The Great Lakes and Lake Nipigon are also drained by the St. Lawrence. The Churchill River and Saint John River are other important elements of the Atlantic watershed in Canada.[54]

The Hudson Bay watershed drains over a third of Canada. It covers Manitoba, northern Ontario and Quebec, most of Saskatchewan, southern Alberta, southwestern Nunavut and the southern half of Baffin Island. This basin is most important in fighting drought in the prairies and producing hydroelectricity, especially in Manitoba, northern Ontario and Quebec. Major elements of this watershed include Lake Winnipeg, Nelson River, the North Saskatchewan and South Saskatchewan Rivers, Assiniboine River, and Nettilling Lake on Baffin Island. Wollaston Lake lies on the boundary between the Hudson Bay and Arctic Ocean watersheds and drains into both. It is the largest lake in the world that naturally drains in two directions.[54]

The continental divide in the Rockies separates the Pacific watershed in British Columbia and Yukon from the Arctic and Hudson Bay watersheds. This watershed irrigates the agriculturally important areas of inner British Columbia (such as the Okanagan and Kootenay valleys), and is used to produce hydroelectricity. Major elements are the Yukon, Columbia and Fraser rivers.[54]

The northern parts of Alberta, Manitoba and British Columbia, most of Northwest Territories and Nunavut, and parts of Yukon are drained by the Arctic watershed. This watershed has been little used for hydroelectricity, with the exception of the Mackenzie River, the longest river in Canada. The Peace, Athabasca and Liard Rivers, as well as Great Bear Lake and Great Slave Lake (respectively the largest and second largest lakes wholly enclosed by Canada) are significant elements of the Arctic watershed. Each of these elements eventually merges with the Mackenzie, thereby draining the vast majority of the Arctic watershed.[54]

The southernmost part of Alberta drains into the Gulf of Mexico through the Milk River and its tributaries. The Milk River originates in the Rocky Mountains of Montana, then flows into Alberta, then returns into the United States, where it is drained by the Missouri River. A small area of southwestern Saskatchewan is drained by Battle Creek, which empties into the Milk River.[54]

Floristic geography

Canada has produced a Biodiversity Action Plan in response to the 1992 international accord; the plan addresses conservation of endangered species and certain habitats. The main biomes of Canada are:

- Tundra

- Boreal forest

- Mixed forest

- Broadleaf forest

- Prairies

- Rocky Mountains, vegetation includes various types of tundra and forests.

- Temperate coniferous forests, of which the Temperate rain forests of coastal British Columbia is an example.

Political geography

Canada is divided into ten provinces and three territories. According to Statistics Canada, 72.0 percent of the population is concentrated within 150 kilometres (93 mi) of the nation's southern border with the United States, 70.0% live south of the 49th parallel, and over 60 percent of the population lives along the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River between Windsor, Ontario and Quebec City. This leaves the vast majority of Canada's territory as sparsely populated wilderness; Canada's population density is 3.5 people/km2 (9.1/mi2), among the lowest in the world. Despite this, 79.7 percent of Canada's population resides in urban areas, where population densities are increasing.[55]

Canada shares with the U.S. the world's longest undefended border at 8,893 kilometres (5,526 mi); 2,477 kilometres (1,539 mi) are with Alaska. The Danish island dependency of Greenland lies to Canada's northeast, separated from the Canadian Arctic islands by Baffin Bay and Davis Strait. The French islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon lie off the southern coast of Newfoundland in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and have a maritime territorial enclave within Canada's exclusive economic zone. Canada also shares a land border with Denmark, as maps released in December 2006 show that the agreed upon boundaries run through the middle of Hans Island.[56]

Canada's geographic proximity to the United States has historically bound the two countries together in the political world as well. Canada's position between the Soviet Union (now Russia) and the U.S. was strategically important during the Cold War since the route over the North Pole and Canada was the fastest route by air between the two countries and the most direct route for intercontinental ballistic missiles. Since the end of the Cold War, there has been growing speculation that Canada's Arctic maritime claims may become increasingly important if global warming melts the ice enough to open the Northwest Passage.

Similarly, the disputed—and tiny—Hans Island (with Denmark), in the Nares Strait between Ellesmere Island and northern Greenland, may be a flashpoint for challenges to overall claims of Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic.[56]

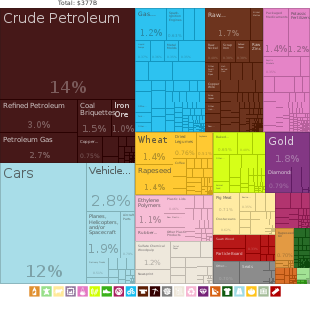

Natural resources

Canada's abundance of natural resources is reflected in their continued importance in the economy of Canada. Major resource-based industries are fisheries, forestry, agriculture, petroleum products and mining.

The fisheries industry has historically been one of Canada's strongest. Unmatched cod stocks on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland launched this industry in the 16th century. Today these stocks are nearly depleted, and their conservation has become a preoccupation of the Atlantic Provinces. On the West Coast, tuna stocks are now restricted. The less depleted (but still greatly diminished) salmon population continues to drive a strong fisheries industry. Canada claims 22 km (12 nmi) of territorial sea, a contiguous zone of 44 km (24 nmi), an exclusive economic zone of 5,599,077 km2 (2,161,816 sq mi) with 370 km (200 nmi) and a continental shelf of 370 km (200 nmi) or to the edge of the continental margin.

Forestry has long been a major industry in Canada. Forest products contribute to one fifth of the nation's exports. The provinces with the largest forestry industries are British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec. Fifty-four percent of Canada's land area is covered in forest. The boreal forests account for four-fifths of Canada's forestland.

Five per cent of Canada's land area is arable, none of which is for permanent crops. Three per cent of Canada's land area is covered by permanent pastures. Canada has 7,200 square kilometres (2,800 mi2) of irrigated land (1993 estimate). Agricultural regions in Canada include the Canadian Prairies, the Lower Mainland and various regions within the Interior of British Columbia, the St. Lawrence Basin and the Canadian Maritimes. Main crops in Canada include flax, oats, wheat, maize, barley, sugar beets and rye in the prairies; flax and maize in Western Ontario; Oats and potatoes in the Maritimes. Fruit and vegetables are grown primarily in the Annapolis Valley of Nova Scotia, Southwestern Ontario, the Golden Horseshoe region of Ontario, along the south coast of Georgian Bay and in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia. Cattle and sheep are raised in the valleys and plateaus of British Columbia. Cattle, sheep and hogs are raised on the prairies, cattle and hogs in Western Ontario, sheep and hogs in Quebec, and sheep in the Maritimes. There are significant dairy regions in central Nova Scotia, southern New Brunswick, the St. Lawrence Valley, northeastern Ontario, southwestern Ontario, the Red River valley of Manitoba and the valleys in the British Columbia Interior, on Vancouver Island and in the Lower Mainland.

Fossil fuels are a more recently developed resource in Canada, with oil and gas being extracted from deposits in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin since the mid 1900s. While Canada's crude oil deposits are fewer, technological developments in recent decades have opened up oil production in Alberta's Oil Sands to the point where Canada now has some of the largest reserves of oil in the world. In other forms, Canadian industry has a long history of extracting large coal and natural gas reserves.

Canada's mineral resources are diverse and extensive. Across the Canadian Shield and in the north there are large iron, nickel, zinc, copper, gold, lead, molybdenum, and uranium reserves. Large diamond concentrations have been recently developed in the Arctic, making Canada one of the world's largest producers. Throughout the Shield there are many mining towns extracting these minerals. The largest, and best known, is Sudbury, Ontario. Sudbury is an exception to the normal process of forming minerals in the Shield since there is significant evidence that the Sudbury Basin is an ancient meteorite impact crater. The nearby, but less known Temagami Magnetic Anomaly has striking similarities to the Sudbury Basin. Its magnetic anomalies are very similar to the Sudbury Basin, and so it could be a second metal-rich impact crater.[57] The Shield is also covered by vast boreal forests that support an important logging industry.

Canada's many rivers have afforded extensive development of hydroelectric power. Extensively developed in British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec and Labrador, the many dams have long provided a clean, dependable source of energy.

Natural hazards

Continuous permafrost in the north is a serious obstacle to development. Cyclonic storms form east of the Rocky Mountains, a result of the mixing of air masses from the Arctic, Pacific, and North American interior, and produce most of the country's rain and snow east of the mountains.

Current environmental issues

Air pollution and resulting acid rain severely affects lakes and damages forests.[58] Metal smelting, coal-burning utilities, and vehicle emissions impact agricultural and forest productivity. Ocean waters are also becoming contaminated by agricultural, industrial, mining, and forestry activities.[58]

Global climate change and the warming of the polar region will likely cause significant changes to the environment, including loss of the polar bear,[59] the exploration for resource then the extraction of these resources and an alternative transport route to the Panama Canal through the Northwest Passage.

Extreme points

The northernmost point of land within the boundaries of Canada is Cape Columbia, Ellesmere Island, Nunavut 83°06′40″N 69°58′19″W / 83.111°N 69.972°W.[60] The northernmost point of the Canadian mainland is Zenith Point on Boothia Peninsula, Nunavut 72°00′07″N 94°39′18″W / 72.002°N 94.655°W.[60]

The southernmost point is Middle Island, in Lake Erie, Ontario (41°41′N, 82°40′W); the southernmost water point lies just south of the island, on the Ontario–Ohio border (41°40′35″N). The southernmost point of the Canadian mainland is Point Pelee, Ontario 41°54′32″N 82°30′32″W / 41.909°N 82.509°W.[60]

The westernmost point is Boundary Peak 187 (60°18′22.929″N, 141°00′7.128″W) at the southern end of the Yukon–Alaska border which is roughly following 141°W but leans very slightly east as it goes North 60°18′04″N 141°00′36″W / 60.301°N 141.010°W.[61][60]

The easternmost point is Cape Spear, Newfoundland (47°31′N, 52°37′W) 47°31′23″N 52°37′08″W / 47.523°N 52.619°W.[60] The easternmost point of the Canadian mainland is Elijah Point, Cape St. Charles, Labrador (52°13′N, 55°37′W) 52°13′01″N 55°37′16″W / 52.217°N 55.621°W.[60]

The lowest point is sea level at 0 m,[62] whilst the highest point is Mount Logan, Yukon, at 5,959 m / 19,550 ft 60°34′01″N 140°24′18″W / 60.567°N 140.405°W.[60]

The Canadian pole of inaccessibility is allegedly near Jackfish River, Alberta (Latitude: 59°2′ 60 N, Longitude: 112°49′ 60 W).[citation needed]

The furthest straight-line distance that can be travelled to Canadian points of land is between the southwest tip of Kluane National Park and Reserve (next to Mount Saint Elias) and Cripple Cove, NL (near Cape Race) at a distance of 3,005.60 nautical miles (5,566.37 km; 3,458.78 mi).

See also

- Atlas of Canada

- Canadian Geographic

- Canadian Rockies

- Extreme points of North America

- List of highest points of Canadian provinces and territories

- List of Ultras of Canada

- Mountain peaks of Canada

- Temperature in Canada

References

- ^ "Canada". The World Factbook. CIA. May 16, 2006. Archived from the original on July 11, 2015. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Gallay, Alan (2015). Colonial Wars of North America, 1512–1763: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 429–. ISBN 978-1-317-48718-0. Archived from the original on March 20, 2018.

- ^ Battram, Robert A. (2010). Canada in Crisis: An Agenda for Survival of the Nation. Trafford Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4269-3393-6. Archived from the original on April 12, 2016.

- ^ Canadian Geographic. Royal Canadian Geographical Society. 2008. p. 20.

- ^ Reuters (2019-06-18). "Scientists shocked by Arctic permafrost thawing 70 years sooner than predicted". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-07-02.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Geography". statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ "The Boundary". International Boundary Commission. 1985. Archived from the original on August 1, 2008. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ "Canada Facts: 25 Interesting and Fun Facts – not only for Kids". Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- ^ National Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. 2005. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7705-1198-2.

- ^ Luckert, Martin K.; Haley, David; Hoberg, George (2012). Policies for Sustainably Managing Canada's Forests: Tenure, Stumpage Fees, and Forest Practices. UBC Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7748-2069-1.

- ^ Bailey, William G; Oke, TR; Rouse, Wayne R (1997). The surface climates of Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-7735-1672-4. Archived from the original on April 12, 2016.

- ^ "The Atlas of Canada – Physical Components of Watersheds". December 5, 2012. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ Sandford, Robert William (2012). Cold Matters: The State and Fate of Canada's Fresh Water. Biogeoscience Institute at the University of Calgary. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-927330-20-3. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017.

- ^ Etkin, David; Haque, CE; Brooks, Gregory R (April 30, 2003). An Assessment of Natural Hazards and Disasters in Canada. Springer. pp. 569, 582, 583. ISBN 978-1-4020-1179-5.

- ^ "Canadian Climate Normals 1971–2000". Environment Canada. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Timoney, K.P.; la Roi, G.H.; Zoltai, S.C.; Robinson, A.L. (1991). "The High Subarctic Forest-Tundra of Northwestern Canada: Position, Width, and Vegetation Gradients in Relation to Climate" (PDF). University of Calgary. Retrieved 2008-03-02.

- ^ a b Kottek, M.; J. Grieser; C. Beck; B. Rudolf; F. Rubel (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated". Meteorol. Z. 15 (3): 259–263. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Retrieved 2007-02-15.

- ^ a b "Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification" (PDF). University of Melbourne. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ "Weather records". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2009-02-10.

- ^ "Calgary International Airport". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- ^ "Charlottetown A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ "Edmonton City Centre Airport". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. August 19, 2013. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ "Fredericton CDA". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Halifax Citadel". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 22, 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Iqaluit A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Climate ID: 2402590. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ ."Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010 Station Data". Environment Canada. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- ^ "Ottawa Macdonald Cartier International Airport". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- ^ "Quebec/Jean Lesage International Airport". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ "Regina International Airport". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Saskatoon Diefenbaker International Airport". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "St John's A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. June 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ "1981 to 2010 Canadian Climate Normals". Environment Canada. 2014-02-13. Climate ID: 6158350. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ "Whitehorse A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Climate ID: 2101300. Retrieved 2014-07-30.

- ^ "Windsor Airport". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- ^ "Winnipeg Richardson International Airport". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ^ "1981 to 2010 Canadian Climate Normals". Environment Canada. 2015-09-22. Climate ID: 1108447. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ^ "Victoria Gonzales Heights". Canadian Climate Normals 1971–2000. Environment Canada. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ "Yellowknife A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Climate ID: 2204100. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ^ a b R. W. McColl (September 2005). Encyclopedia of world geography. Infobase Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-8160-5786-3. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ "Geography". www.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ^ a b Peter Haggett (July 2001). Encyclopedia of World Geography. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-0-7614-7289-6. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ Joseph A. DiPietro (2012). Landscape Evolution in the United States: An Introduction to the Geography, Geology, and Natural History. Newnes. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-12-397806-6.

- ^ "Nunataks - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2020-01-15.

- ^ Bryan Pezzi (2006). The St. Lawrence Lowlands. Weigl Educational Publishers Limited. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-55388-152-0.

- ^ Wayne Grady; David Suzuki Foundation (26 September 2007). The Great Lakes: the natural history of a changing region. Greystone/David Suzuki Fdtn. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-55365-197-0.

- ^ Peter J. Wangersky (2006). Estuaries. Springer. p. 122. ISBN 978-3-540-00270-3.

- ^ a b Joseph Anthony Mandarino; Violet Anderson (1989). Monteregian treasures: the minerals of Mont Saint-Hilaire, Quebec. CUP Archive. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-521-32632-2.

- ^ a b George Philip and Son; Oxford University Press (2002). Encyclopedic World Atlas. Oxford University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-19-521920-3.

- ^ Shoalts, Adam (2011). "Canada's Worst Natural Disasters of All Time". Canadian Geographic. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016.

- ^ Jessop, A. Geological Survey of Canada, Open File 5906. Natural Resources Canada. pp. 18–. GGKEY:6DLTQFWQ9HG. Archived from the original on April 12, 2016.

- ^ Atlas of Canada (February 2004). "Distribution of Freshwater". Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- ^ Atlas of Canada (April 2004). "Facts about Canada – Lakes". Archived from the original on April 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

- ^ "Rivers: Longest rivers in Canada". Environment Canada. July 22, 2013. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Drainage Basin". thecanadianencyclopedia. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ^ Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "Population, urban and rural, by province and territory (Canada)". www.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Satellite imagery moves Hans Island boundary: report". CBC News. The Canadian Press. 2007-07-26. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ^ "3-D Magnetic Imaging using Conjugate Gradients: Temagami anomaly". Geological Survey of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. Archived from the original on 2009-07-11. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ a b David R Boyd (2011). Unnatural Law: Rethinking Canadian Environmental Law and Policy. UBC Press. pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-0-7748-4063-7.

- ^ "The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Toporama". Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada.

- ^ "141st Meridian Boundary Points". International Boundary Commission. Retrieved 2010-12-20.

- ^ "Canada". The World Factbook. CIA.

Further reading

- Bailey, William G; Oke, TR; Rouse, Wayne R (1997). The surface climates of Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-1672-7.

- Drushka, Ken (2003). Canada's forests: a history. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2660-9.

- Etkin, David; Haque, CE; Brooks, Gregory R (2003). An Assessment of Natural Hazards and Disasters in Canada. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-1179-5.

- Feldhamer, George A; Thompson, Bruce Carlyle; Chapman, Joseph A. (2003). Wild mammals of North America (2nd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801874165.

- Fick, Steven (2004). The Canadian atlas: our nation, environment and people. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 0888507704.

- French, Hugh M; Slaymaker, Olav (1993). Canada's Cold Environments. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-0925-9.

- Hudson, John C (2002). Across this land: a regional geography of the United States and Canada. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6567-0.

- Nils, John Macoun; Kindberg, Conrad (1883). "Catalogue of Canadian plants". Geological Survey of Canada.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

- Government of Canada – The Atlas of Canada

- Canadian Geographic – The Canadian Atlas Online

- The Barren Lands Collection and Expedition maps, University of Toronto

- The Barren Lands Collection and Expedition maps, University of Toronto

- Cartography of Canada – The Canadian Map Online

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.